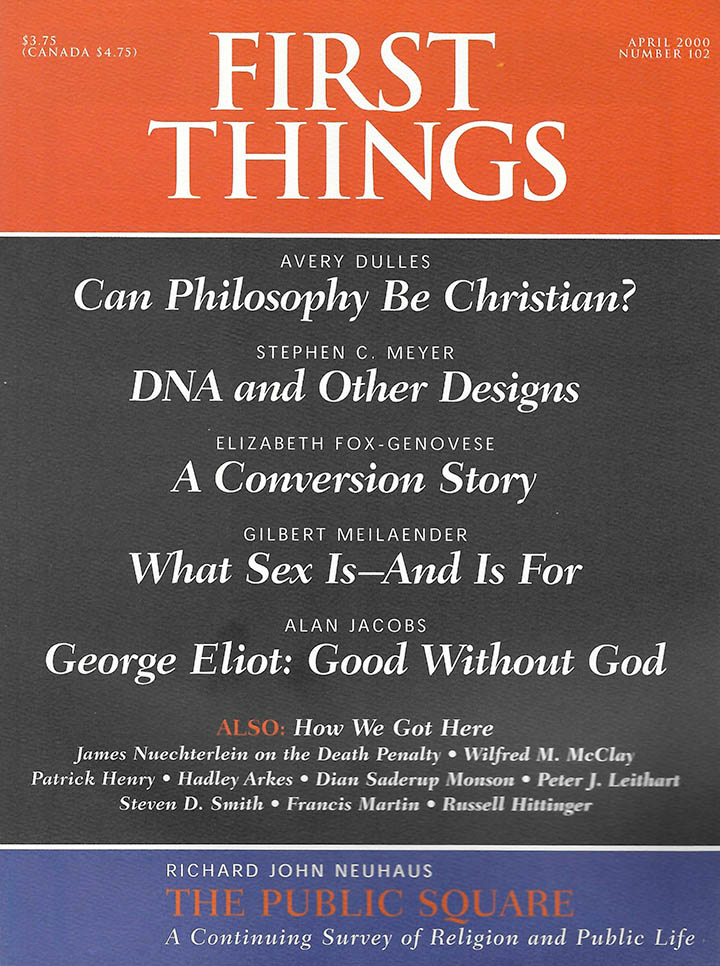

So David Frum sends me his new book, with the inscription, “Hope you like this one better than the last.” I definitely do. The last one was Dead Right, in which Mr. Frum contended that conservatism was making a big mistake by letting itself be distracted by the social and cultural issues when what really matters is economics. (I oversimplify, a little.) The new book is How We Got Here: The Decade That Brought You Modern Life—for Better or Worse (Basic, 418 pages, $25).

It does not neglect economics (Frum is particularly effective in describing the cultural and moral impact of inflation), but the bulk of the book is devoted to the fads, ideas, movements, inspirations, and delusions that marked the 1970s as a decisive turning point in the way Americans live. It is a rollicking good read, as well as a catalogue of the people and crazes that shaped what Frum, following Auden’s judgment of the 1930s, calls “a slum of a decade.” Those of a certain age will frequently be prompted to think, “Ah yes, how could I have forgotten that?” Younger readers are in for a lively tour of what to them are “the olden days.”

I’m not inclined to argue with Frum’s claim that it was the seventies and not the sixties that most influenced the last of the twentieth century. This habit of “decadizing” history is mainly a book publishing gimmick. Books on the sixties have been done to death. In any event, the story of the seventies is in large part the working out of the unbounded liberationisms proclaimed by the avant garde of the sixties, and I’m not sure that David Frum would want to waste much time in disagreeing with that. Almost everything is here: divorce up, marriage down; the marginalizing of the urban underclass; mushrooming pop therapies centered on the great god Me; school busing and related schemes of the elite imposed upon their supposed inferiors; the rise of identity politics and the crash of the academy; feminism’s liberation of men from sexual responsibility; the hucksters of environmental apocalypse; bilingualism and the non-assimilation of a flood of immigrants; “homophobia” and the role of gays as arbiters of high correctness; smoking as heresy against the cult of the healthy self; the collapse of confidence in institutions, and in politics itself. When your friends tell you that your view of the cultural, moral, and social depredations of recent decades is exaggerated, you can pull out How We Got Here and cite chapter and verse.

On religion, Frum tells the story in a manner familiar to readers of this journal: the demoralization and decline of the mainline/oldline, the growth of conservative evangelicalism, and so forth. I do wish he had not cited what he calls President Eisenhower’s “deservedly famous statement”: “A system of government like ours makes no sense unless founded on a firm faith in religion, and I don’t care which it is.” The statement is indeed famous but not deservedly so, since nobody has been able to document that Eisenhower ever said it. Among other complaints I have, Frum greatly underestimates the vitality of Catholicism in America, and his treatment of evangelicalism inclines to the indulgence of caricatures. He is undoubtedly right in saying that at the end of the seventies many people “hungered for religion’s sweets, but rejected religion’s discipline; wanted its help in trouble, but not the strictures that might have kept them out of trouble; expected its ecstasy, but rejected its ethics; demanded salvation, but rejected the harsh, antique dichotomy of right and wrong.” Cotton Mather said much the same in 1725, and preachers will likely be saying it until Our Lord returns in glory. A difference in the seventies is that more of the country’s religious leadership turned toward the marketing techniques of pandering to the “felt needs” of the spiritually debased. But that, too, has a long history. The treatment of religion, while devastatingly accurate on some scores, is not the strongest part of the book.

Despite everything, and contrary to the massive evidences of depredation that he musters, Frum wants to sound an upbeat note. Along the way there is even this: “The 1970s were America’s low tide. Not since the Depression had the country been so wracked with woe. Never—not even during the Depression—had American pride and self-confidence plunged deeper. But the decade was also, paradoxically, in some ways America’s finest hour. . . . For a short time [the American people] behaved foolishly, and on one or two occasions, even disgracefully. Then they recouped. They rethought. They reinvented. They rediscovered in their own past the governing principles of their future. Out of the failure and trauma of the 1970s they emerged stronger, richer, and—if it is not overdramatic to say so—greater than ever.” It is not overdramatic and it is not paradoxical; on the basis of the book’s ample documentation, joined to the experience of those who were there then and are here now, it is, as David Frum might say, dead wrong.

In the actual conclusion of the book, Frum is somewhat more tempered. “Early twenty-first century America is a newly cautious society, not a remoralized one, and even that caution extends only so far.” But the final sentence holds out the wan prospect that we are moving not backward but onward “away from the follies and triumphs of the 1970s and toward something new: new vices, new virtues, new sins—and new progress.” Ah yes, progress. It is a very American book after all. The triggers of what went wrong in the seventies, according to Frum, were Vietnam, race, inflation, and, maybe, technology. Abortion—the single most fevered and volatile issue in our public life—receives but passing notice. That is the issue inseparable from a host of changes related to the redefining and redesigning of human life, and our moral responsibilities to one another. Some of those more grim prospects were explored by writers in the symposia in our January and March issues. David Frum shies away from digging so deep, lest he further undercut the shaky platform from which he issues what I expect he also recognizes is a limp half-cheer for progress.

But do I like the book better than the last one? Most definitely. In fact, I warmly recommend it for its frequently incisive cultural criticism, its spirited jeremiads, and its provision of detail and documentation about where we have been. Dr. Johnson was in large part right when he said that mankind has a greater need of being reminded than of being instructed. How We Got Here is an engaging and instructive reminder.

A New Purity Culture

I grew up in evangelical purity culture. Well-thumbed copies of I Kissed Dating Goodbye, Every Young Man’s…

Noble Rituals

What are rituals? Rituals are not just routines. Mere routines are pragmatic and instrumental. Rituals transcend routines…

Goodbye, Childless Elites

The U.S. birthrate has declined to record lows in recent years, well below population replacement rates. So…