• Now it seems probable that it’s not a question of whether but of how what used to be the Anglican communion will break up. I doubt if, even twenty years ago, anybody dreamed that the shattering would come over the question of homosexuality. But, as Philip Turner explains in this issue, other shatterings prepared the way. “God has once again brought an Easter out of Good Friday,” declared an exultant V. Gene Robinson after his election as Bishop of New Hampshire was approved by his episcopal colleagues. It’s not the Second Coming, but another Easter is nothing to sniff at. Robinson, who left his wife and children in order to satisfy his sexual needs, addressed the bishops in solemn assembly thusly: “I believe that God gave us the gift of sexuality so that we might express with our bodies the love that’s in our hearts. I just need to tell you that I experience that with my partner. In the time that we have, I can’t go into all the theology around it, but what I can tell you is that in my relationship with my partner, I am able to express the deep love that’s in my heart, and in his unfailing and unquestioning love of me, I experience just a little bit of the kind of never-ending, never-failing love that God has for me. So it’s sacramental for me.” I just need to tell you that it’s probably just as well that he didn’t go into all the theology around it.

• In a Times story on how September 11 is still affecting New Yorkers, we are told: “There continues to be a minority of people who avoid the subway, stay away from skyscrapers, sleep fitfully, find new solace in religion.” Ah, well, in time they’ll overcome such quirkiness. But then there is the statement that they continue to find “new” solace in religion, which implies they found it there before. This may be a more long-term problem.

• The Archbishop of Boston, Sean O’Malley, has agreed to an $85 million settlement. The lawyers will each get an automatic $750,000 to cover legal fees, plus one third of the amount each client gets. The lawyers did all right by themselves. Forbes magazine has run blistering articles on how the scandal lawyers have been soliciting for clients, giving fat contributions to the victim organizations, and exploiting “recovered memory” charges that would not stand a moment’s scrutiny in court. So what’s new? Unlike priests, lawyers had no honorable reputation to lose. That’s very unfair, of course, to many conscientious lawyers, but they knew that when they signed up for law school. An interesting twist in the Boston settlement is that the archdiocese entered an iron-clad agreement to keep confidential any counseling files it has on those bringing charges. In some cases, such files might indicate mental instability or a desire to extort money by making false charges. I’m firmly for keeping confidential matters confidential. At the same time, however, the archdiocese is required to reveal all confidential files on priests who are accused, including communications with the papal nuncio and the Holy See. All crimes should be investigated, including the crime of attempted extortion. In Boston, lawyers and an overreaching state attorney general have not limited themselves to crime, real or alleged. They have asserted their intention to run the Church. As for the privacy rights of priests or the right of the Church to govern itself, forget it. But Archbishop O’Malley is probably right in acting quickly to move on from the legal, financial, and media nightmare of the last two years. Addressing the moral, spiritual, and leadership failures that produced the nightmare is work enough for the years ahead. I have known the archbishop for a long time, and he is a very good man. He is intelligent, articulate, orthodox, courageous, and personable. He knows, and his life evinces his knowing, that without holiness ministerial leadership rings hollow. He was the right choice for Boston, and we should join the faithful there in praying that he goes from strength to strength.

• After some controversy over how it was being done, the National Jewish Population Survey has been released to the general satisfaction of earlier critics. The survey finds that the Jewish population of the U.S. is smaller and older than it was at the last survey ten years ago. There are 5.2 million Jews, a drop of 300,000, despite a large wave of immigrants from the former Soviet Union. That is about 1.8 percent of the population. Forty-seven percent of Jews marry non-Jews, and two-thirds of their children are not being raised as Jews. Before 1970, only 13 percent married non-Jews. Moreover, Jews have a lower birth rate than most Americans. There is always the big question of defining who is a Jew. For purposes of the survey, a Jew is someone who says he is Jewish or has at least one Jewish parent or had a Jewish upbringing and has not converted to another monotheistic religion, such as Christianity or Islam. Forty-six percent of adult Jews belong to a synagogue, and of them 39 percent are Reform, 33 percent Conservative, and 21 percent Orthodox. (The rest belong to smaller and generally more liberal groups.) The median age of Jews is forty-two, while for all other Americans it is thirty-five. While 43 percent of Jews who have no Jewish education marry non-Jews, the figure falls to 23 percent of those who go part-time to an afternoon Hebrew school, and to seven percent of those who attend a full-time school or yeshiva. The 22 percent of American Jews who live in the West are, by all measures, much less Jewishly connected.

• After the 1968 election, Milton Himmelfarb wrote that Jews live like Episcopalians and vote like Puerto Ricans. Thirty-two years later, in the election of 2000, Jews were still a little ahead of Hispanics in their support for the Democrats. But September 11, 2002 changed many things, says Milton’s formidable sister, Gertrude Himmelfarb, in an essay in an important new book, Religion as a Public Good: Jews and Other Americans on Religion in the Public Square (Rowan & Littlefield). She writes: “This is the lesson that all of us, Jews and non-Jews, may learn from recent history: that religion is, by and large, a force for good, and that it does not become less good when it emerges from the home and temple and assumes its rightful place in society. Jews in particular have learned a great deal from the Bush Administration and from the President himself. We are no longer so fearful of the rhetoric of religion, which comes naturally to a benign and tolerant President, or, for that matter, of the rhetoric of morality (the ‘axis of evil’), which was so appropriate a response to the events of 9/11. Nor are we so fearful of the conservatives, who have understood, as many liberals have not, the intimate relationship between America’s War against Terrorism and Israel’s. Nor are we so fearful of the evangelicals who have been among Israel’s staunchest defenders. The nature of public discourse has changed, and it will inevitably affect our attitudes toward such issues as faith-based initiatives, or prayers in schools, or school vouchers. There are difficult administrative and constitutional problems to address in all of these cases. But however they are resolved, we are already, in a sense, ahead of the game. The Jewish religion is no longer bound by the liberal credo. More and more Jews have begun to recognize that the separation of church and state does not require a comparable separation of religion and society. There may even come a time when Jewish women will no longer feel that the ‘right of choice’ (that is, the unrestricted right of abortion) is their principle article of religious faith. 9/11 has called into question a good many of the old verities and taboos, not only about foreign policy but about domestic and cultural affairs as well.” Gertrude Himmelfarb concludes her essay by admitting that she is writing in one of “my more optimistic moments.”

• Because James Wood is an always interesting critic and essayist, because he has written provocatively about his atheistic views, and because authors whom he has criticized are piling on in trashing this his first novel, one approaches The Book Against God (Farrar, Straus & Giroux) with the hope that it is something really fine. It is much more engaging than some of the critics have allowed. Thomas Bunting, a young man who is permanently procrastinating about his Ph.D. thesis in philosophy in favor of making notes for his own book against God (called BAG), and who is a chronic har, lives against the presence of his imperiously benign father, a vicar in a village near Durham. Almost everyone in the book is much more attractive than Thomas (who may or may not be James Wood), including his wife Jane, a concert pianist, who takes until page 208 to exclaim in exasperation, “Oh, grow up. Please, Tommy.” The authorial voice is distanced from Thomas’ (Wood’s?) atheistic ramblings, which never rise above Theodicy 101—if God is good and almighty, why is there so much wrong with the world? Thomas is not moved by the persistent suggestion of Jane and others that he and his way of thinking is one of the main things wrong with his part of the world, and the book ends on a note of nostalgic protest that, all arguments notwithstanding, reality should be as innocent and promising as it seemed when he was his father’s little boy. That may not sound like much of a story, but there are delightfully comic moments, and an intimation that Tommy might grow up when he dares to say yes to life by acquiescing in Jane’s desire for children. I don’t know what our reviewer is going to say about the book, but I thought I would sneak in this anticipatory strike of appreciation.

• For understandable reasons it did not receive much attention but, for the record, the Central Committee of the Geneva-based World Council of Churches (WCC) has called on the UN to investigate Saddam Hussein’s crimes in Iraq and any “war crimes” committed by the “occupying powers,” including the “illegal resort to war.” The WCC news service notes that the resolution “implied that U.S. President George W. Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair might appropriately be charged with war crimes.” Clifton Kirkpatrick, Stated Clerk of the Presbyterian Church (USA) and a Central Committee member, said he was “deeply grateful” for the resolution because it “gives some understanding of what we’re to do next.” Others think there is absolutely no telling what the WCC will do next. My own view, I am sorry to say, is that what the WCC will do is sadly predictable. During four decades of the Cold War it pretty much took its marching orders from another Central Committee on the wrong side of freedom, and its anti-American propensities remain unbounded. Which is a pity, because the U.S. needs to lead the world by persuasion, and that requires international interlocutors interested in consultation rather than scoring polemical points. And it is more of a pity when an institution created to advance Christian unity turns itself into an anti-ecumenical agency exacerbating further division along political divides. As I say, the WCC action received slight attention and a spokesman allows it is “not likely” that the UN will follow its advice. On the other hand, these days there is no telling what the UN might do. But that’s a pity for another time.

• “On behalf of His Holiness RAEL, Dr. Brigitte Boisselier, and the sixty thousand Raelians living in eighty-four countries, I want to express our outrage regarding the article by Susan Palmer in the article ‘UnRael!’ in the Spring 2003 issue of Religion in the News.” So begins a letter to the editor by Nicole Bertrand, who bears the title “Raelian Bishop.” Palmer was reporting on the announcement of the Raelian-related organization Clonaid that it had cloned a human baby, and maybe several. Palmer responds: “I am sorry if the Realians found my article unfair….1 personally have found much to admire about the Realians…. I am by no means convinced that Baby Eve was the shortsighted hoax the media made it out to be, and expect to receive new insights into the modus operandi of the largest UFO religion in the world when the mystery of the disappearing clones is finally cleared up.” Readers often ask why I have not commented on this or that, to which I respond that a journal on religion, culture, and public life cannot take note of everything. So why give space to the modus operandi of the largest UFO religion in the world? Chalk it up to eccentricity. Do you suppose there are larger UFO religions elsewhere?

• The Prime Minister of Canada, Jean Chretien, is a Catholic and strongly supports same-sex marriage. Bishop Fred Henry of Calgary, Alberta, said the PM “doesn’t understand what it means to be a good Catholic,” and, if he didn’t start getting serious, he “risks his eternal salvation.” Well, you can imagine. Joining in the media outrage was the Minister of Heritage, Sheila Copps, who said she was appalled by the Bishop’s statement: “I think that’s something that each person reconciles with their own maker and that’s not something that you take to the political arena. Every Canadian, regardless of their religion, has to reconcile their beliefs with their god, their Allah, their guru, that’s why we live in a country that separates the views of religion from the views of the state.” The theological view of the state is that people have their own makers, their own gods, and, even, their own Allahs. Bishop Henry dissents from the state religion and gave offense by suggesting that the PM should make up his mind about whether he wants to continue in the community of dissent that is the Church. Henry’s refusal to believe in the many gods of the society puts him in a position not unlike that of the early Christians who were accused of atheism. Canada may be finding its long-sought national identity as the North American social laboratory for experiments in unbounded muddle-headedness.

• E. Brooks Holifield has written an impressive history, Theology in America: Christian Thought from the Age of the Puritans to the Civil War (Yale University Press, 617 pp., $35). Adam Kirsch, the books critic of the New York Sun, finds it an engaging curiosity, noting that “theology now seems halfway between a medieval relic, like alchemy, and a tolerated academic oddity, like classics…. This is a cause for celebration: our principled secularism is part of what makes America the hope of the world. But American theology remains a valuable legacy, and there could be no better introduction to it than Theology in America.” A legacy, no doubt, but why valuable? In Mr. Kirsch’s telling, it is more like Mr. Holifield has interestingly presented the deranged notes that a batty aunt in the attic kept in a shoebox. Admittedly, that “principled secularism” does hint at something like a replacement theology, and talk about “the hope of the world” rises to the level of eschatological promise. Kirsch does allow that, for all of theology’s antiquated riddles, thinkers such as Jonathan Edwards did try to resolve them “in more philosophically precise terms.” Mr. Kirsch cannot be accused of philosophical precision, or even awareness, which I expect he will take as a compliment.

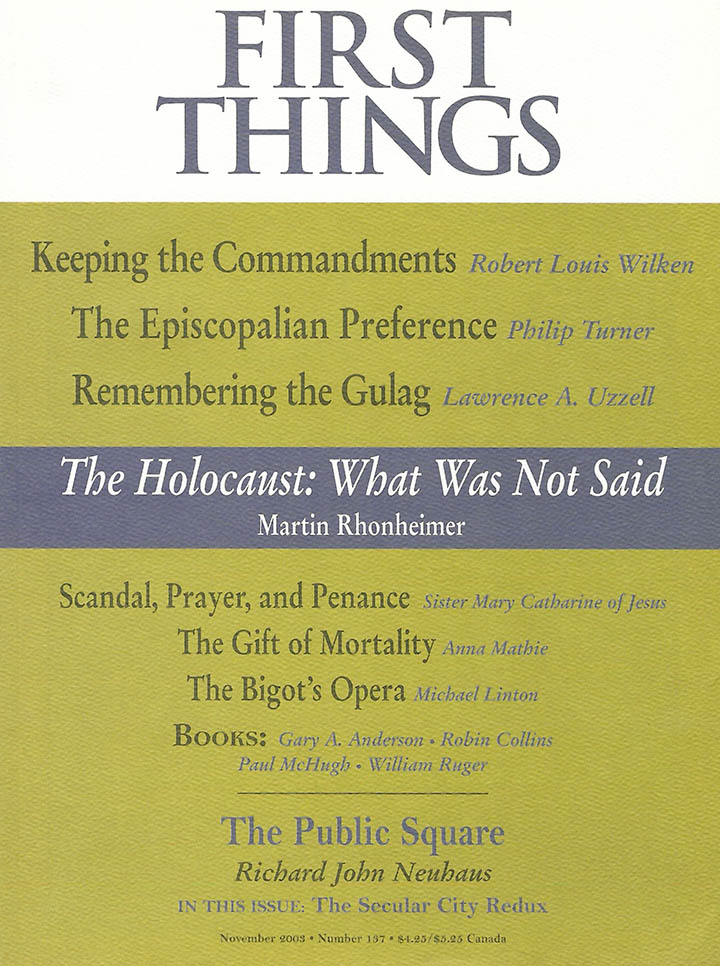

• “I believe, all things considered, morally and politically, Pius XII acted appropriately and made the right decisions.” So says Sir Martin Gilbert in an extensive interview in Inside the Vatican. Gilbert, who is Jewish, is the acclaimed biographer of Winston Churchill, and the most recent of his many books, The Righteous: The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust, was favorably noted in our August/September issue. In the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem, there are a little over twenty thousand Christian rescuers of Jews who have been given the title, “Righteous Among the Gentiles.” These are people–mainly Catholics, if for no other reason than the dominance of Catholicism in the most affected areas of Europe–who risked their lives to save Jews, and Gilbert and other scholars believe that the actual number of rescuers is much higher. Many of the Righteous Gentiles were, along with those they were rescuing, captured and killed. Their names have been lost to history, but not to God. Gilbert says, “It could well be that half a million Jews saved is not an exaggerated figure. We are certainly talking about something on the scale of hundreds of thousands rather than tens of thousands.” Pinchas Lapide, another Jewish scholar, estimates that the number of Jews rescued is over 800,000, although many scholars think that figure too high. In any event, Martin, along with others, strongly underscores that the bishops, priests, nuns, and courageous lay people who engaged in rescuing Jews understood that they were acting in accord with Catholic teaching and with the blessing of Pope Pius XII. Gilbert says, “Hundreds of thousands of Jews saved by the entire Catholic Church, under the leadership and with the support of Pope Pius XII, would, to my mind, be absolutely correct. The longest article we have ever published in these pages is Ronald Rychlak’s “Goldhagen v. Pius XII” June/July 2002). That article, in our judgment, is a devastating scholarly refutation of the meretricious polemics of the likes of Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, James Carroll, and John Cornwell, who charge Pius XII with indifference, and even with crimes against humanity, during the Holocaust. In the present issue we publish Father Martin Rhonheimer’s assessment of less admirable dimensions of Catholic leadership during those times of terror. Yes, there were the rescuers; and yes, the record of Catholic leaders is far better than that of Protestants, especially in Germany; and yes, we must be exceedingly careful in judging those caught in circumstances dramatically different from ours. All that being said, we must also understand the story told by Fr. Rhonheimer. Such understanding is part of the “purification of memory” for which Pope John Paul Il has so incessantly called. It is also an essential part of appreciating the timidity, evasions, and rationalizations to which bishops, too, are sometimes prone. Very pertinent to our own historical circumstance, Fr. Rhonheimer’s article highlights the need for the Church’s voice to be public and explicit in defending innocent human life and protesting great moral evils. Many who today blame the Church for being silent then want the Church to be silent now on issues such as abortion. They do not recognize their contradiction, failing to see or refusing to see the evil of the present. Or, if they see it, averting their eyes and muting their protest, as did most, including religious leaders, during those years when moral duty was so glaringly obvious–to us.

• In August, about one third of the priests of Milwaukee, 163 to be exact, signed a letter to the U.S. conference of bishops. “We urge that from now on celibacy be optional, not mandatory, for candidates for the diocesan Roman Catholic priesthood. … We remain aware that great charism that it is–some future priests will continue to choose celibacy. The primary motive for our urging this change is our pastoral concern that the Catholic Church needs more candidates for the priesthood, so that the Church’s sacramental life might continue to flourish.” It is an interesting initiative. One might point out that, if celibacy is a great charism, as in a gift, it is not chosen. Of course, one may choose whether or not to accept the gift. The experience of communions that have married clergy is not encouraging. In those communities there are single clergy who are homosexual, and married clergy who declined the gift for fear of being thought homosexual. There are very few celibate clergy. Because the bishops conference is designed to relate to bishops, its president, Bishop Wilton Gregory, responded to the letter in a letter to Archbishop Timothy Dolan of Milwaukee. He pointed out that there are many ways priests can encourage vocations to the priesthood, and that “service to Christ and his people through a celibate priesthood was not an arbitrary imposition by the Church of a particular moment in history, but rather the result of a growing consciousness, already from the earliest centuries of the Church’s history, that there was a powerful congruence between priesthood and the celibate example of Christ himself.” In the archdiocesan newspaper, Dolan commented on the letter and the media’s lionizing of those who signed it: “The reports would have us believe that this letter is revolutionary and novel, requiring courage’ in a climate where free discussion on this issue is rare. Courage, I would propose, characterizes rather all our priests— those who signed and the 72 percent who did not–who live their celibate chastity with fidelity and joy; courage characterizes our married couples who generously and obediently live out their vows; courage is found in our young people and unmarried adults who follow the teaching of Jesus, the Bible, and the Church on the beautiful virtue of chastity; courage is found in those writers—priests, religious, lay, Catholic and non-Catholic–who defend such a countercultural virtue as celibacy in a world that feels one cannot be happy or whole without sexual gratification.” Dolan says he agrees with a priest who told him, “The problem is not that we don’t talk about optional celibacy; the problem is that we’ve talked it to death the last forty years.” “This,” Dolan adds, “is the time we priests need to be renewing our pledge to celibacy, not questioning it. The problems in the Church today are not caused by the teachings of Jesus and of his Church, but by lack of fidelity to them.” Archbishop Dolan, who has been in Milwaukee only a year, leads in a manner that might be described as affably resolute. He understands and effectively communicates the high adventure of fidelity. In short–and in a time, like most times, when such is in short supply–he is a bishop who knows how to bishop.

• “Is Christ Divided? Dealing with Diversity and Disagreement” is the title of a powerfully suggestive lecture delivered at Catholic University by Father Joseph Komonchak, who has written extensively and knowledgeably on the Second Vatican Council. He traces the ways in which the bishops at the council dealt with agreements and disagreements, resulting in authentic deliberation and, sometimes, deliberate accommodation without compromising the common devotion to speaking the truth. Then there is this noteworthy passage: “There is one problem in the contemporary Church to which I don’t think there is a parallel in the experience of Vatican II. At the council the differences I have pointed to were differences within the household of faith, and by faith here I mean the substantive sets of meanings and truths that constitute the Church. The council fathers may have argued fiercely over particular points, including whether a particular matter had been settled by Irent or by the ordinary magisterium; but they were at one in recognizing the constitutive role of doctrine and the importance of defending the faith once delivered to the saints. They took it for granted that the Church is first of all the community of those who believe that God was in Christ reconciling the world to Himself. But I think what Charles Taylor describes as ‘the new individualism’ is very widespread in our culture and even among Catholics. This is the tendency to reduce religion to one’s own very personal, even private spirituality (‘following your bliss,’ ‘being true to your own inner self’), which then becomes the criterion by which to decide what tradition, it any, to follow, what community, if any, to enter, what beliefs to hold, if any. As Taylor argues, this is an almost perfect exemplification of William James’ definition of religion as ‘the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider divine. Out of this inner reality, James said, ‘theologies, philosophies, and ecclesiastical organizations may secondarily grow.’ This seems to me different from the often deplored cafeteria Catholicism’ (although it may be one of its inspirations), that is, picking and choosing among Church teachings; that at least allowed that there were Church teachings. For those whom I am describing it is nearly incomprehensible that one’s spirituality might need itself to be tested against any external reality or authority. If this phenomenon is as widespread as Taylor thinks it is, then it may be that many of the disputes about doctrines or worship or morality that so often occupy Catholics are rather missing the point: there are many people claiming to be Catholic who couldn’t care less.” Komonchak concludes with this fine statement by the French theologian Yves Congar, a statement deserving of attention not only by Catholics and Christians but by all who are determined to settle for nothing less than the truth: “Let our ideas be clear; let us present them in all their rigor. This is a condition of honesty. Let us serve them with all our might. This is the exercise of our courage. But just as we leave a margin on our writing paper for revisions, for corrections, for things not yet found, for the truth for which we can still only hope, let us leave around our ideas the margin of fraternity.”

• Initiatives abound to redress the problem that historian Mark Noll described as “the scandal of the evangelical mind.” Here, for instance, is the premier issue of the Brandywine Review of Faith & International Affairs. The title refers to the Brandywine Creek near Eastern University in St. Davids, Pennsylvania, where the review is published under the editorship of Robert A. Seiple, former Eastern president and the first U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom. In the statement of purpose Seiple writes: “Against the secularist definition of a tolerant public square, which would have Christians and others check their deepest commitments at the gate, and against the relativist definition, which would have everyone pretend that profound differences do not really mean anything, we advocate for a civil yet robustly pluralistic public square.” (I feel sincerely flattered.) Interestingly, in explaining why religion is now receiving more attention in the discussion of international affairs, Seiple highlights not resurgent Islam but “the rise of religious persecution to a prominent place on the human rights agenda.” The two factors overlap, of course, but that way of putting it is, well, interesting. The first issue includes an open letter to President Bush signed by about a hundred evangelical Protestant leaders, including editor Seiple. The letter underscores that “the American evangelical community is not a monolithic bloc in full and firm support of present Israeli policy.” While the signers “abhor and condemn” the suicide bombings and other acts of violence in the current Palestinian intifada, they write: “We urge you to provide the leadership necessary for peacemaking in the Middle East by vigorously opposing injustice, including the continued unlawful and degrading Israeli settlement movement. The theft of Palestinian land and the destruction of Palestinian homes and fields are surely some of the major causes of the strife that has resulted in terrorism and the loss of so many Israeli and Palestinian lives. The continued Israeli military occupation that daily humiliates ordinary Palestinians is also having disastrous effects on the Israeli soul.” So one may safely assume that the new review is not in the Christian Zionist camp. In any event, a publication marked “Volume 1, Number 1” is always bracing evidence of irrepressible hope. (For more information about the Brandywine Review, write 1300 Eagle Rd., Eastern University, St. Davids, Pennsylvania 19087 or www.cfia.org)

• We carried the story of Lieutenant Ryan Berry, a young married man stationed at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota (Daniel P. Maloney, “Sex and the Married Missiler,” February 2000). He asked for an exemption from the routine in which he would be alone with a female officer in a small underground bunker for twenty-four to forty-eight hours. This exemption would accommodate, as his request put it, his Catholic belief that he should avoid situations in which he might “develop inappropriate intimacy–even platonic–with a woman who is not his wife.” In an older parlance that is known as “an occasion of sin,” and Berry asked for permission to avoid it, absent military necessity. For a while, permission was granted, but then a new commander refused and put derogatory statements in Berry’s official record, thus destroying his military career. Now, years later and with the help of the Becket Fund, a feisty legal defender of religious freedom, Berry has prevailed and the U.S. military has agreed to remove all derogatory material from his records. A small victo-ry, some might say, but nothing is small in the defense of religious liberty. Chalk up another one for the Becket Fund.

• Marian E. Crowe of the University of Notre Dame writes to say that we need not speculate about what Hilaire Belloc might say about the Catholic infidelity scandals. She thinks he said it in his little book, How the Reformation Happened. Not all the parallels are fair or accurate, but Belloc’s advice on how the Church should have responded to the Protestant challenge in the sixteenth century is, I think, suggestive for our admittedly different circumstance and is by no means limited to the present round of scandals: “Obviously the perfect thing to do in such cases—if there were no conditions of matter, time, and space, if most men were intelligent, pure in motive and heroic, instead of being, as most men are, stupid, corrupt, and cowardly— would be to perform what the Catholic Church herself calls Penance. Obviously the attack upon the Catholic Church would have no success if all the officials thereof in the early sixteenth century had themselves come forward in a body denouncing their own guilt; the pluralities, the lay appropriations, the shame of their worldly lives, the gross scandals of impurity, the oppression of the poor, the exaggeration of mechanical aids to religion, the occasional use of fraud in it, the widespread use of extortion in clerical dues and rents, the chicanery of clerical courts. If the very many church officials who were guilty of evil living had beaten their breasts, repented, and turned anchorite; if the many who were swollen with riches had abandoned them and given them to the poor; if such of the cultured Renaissance prelates as had come to ridicule the Mysteries had suddenly felt the wrath of God–then all would have righted. So fruitful is repentance. But men do not act thus after long habit. It is only after they have felt the consequence of wrongdoing, and often not then, that they admit reality. Repentance, which should precede chastisement, is commonly its consequence.”

• “I guess I’m an existentialist,” announced the eighteen-year-old upon discerning no meaning in his life. The meaning of “existentialism” in this and so many other connections is equally obscure. Werner J. Dannhauser takes on George Cotkin’s Existential America in the pages of the Weekly Standard. Of Cotkin he says: “Optimistic and benevolent, he seems to think that since existentialism is a good thing and America is a good thing, existentialism in America must be a very good thing.” One problem, says Dannhauser, is that, for Cotkin and many others, existentialism seems to be compatible with almost anything. “One can prove that there can be no Christian existentialists, since existentialism portrays man as floundering in meaningless chaos–and then notice that in real life Christian existentialists abound. Similarly, one can prove there can be no Marxist existentialists, since existentialism insists on man’s complete (and dreadful) freedom–only to discover that Marxist existentialists are thick on the ground. At times it seems that anybody who ever experienced a bit of unhappiness and concluded that life is no bowl of cherries qualifies as an existentialist. Cotkin hardly lays this suspicion to rest, granting as he does existentialist legitimacy to Walter Lippmann, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Woody Allen, Paul Newman in Cool Hand Luke, and even Abraham Lincoln.” In dealing with existentialism, says Dannhauser, there are giants to be wrestled with, but they are given slight attention by Cotkin. Kierkegaard, for instance, “a towering thinker who employed reason’s power to expose reason’s limits and did so with unmatchable wit and fervor.” A fervent Christian, Kierkegaard railed against the church establishment, “thereby becoming the patron saint of all who think they are profound when they say, ‘I believe in God but not in organized religion.'” In Dannhauser’s judgment, Existential America is altogether too much American and too little existential.

• Thirteen years ago, Sister Mary Rose McGeady was asked by John Cardinal O’Connor to take over Covenant House, which was wracked by sexual and financial scandal and close to going under. Covenant House, established by Father Bruce Ritter, works with street kids, mainly multiply-troubled teenagers who have run away from home. Sister Mary Rose is one formidable woman, and she turned the apostolate around to the point where it now has a budget of nearly $120 million and works with sixty thousand teenagers through centers in twenty-two cities. She joined the Daughters of Charity when she was a teenager and there were 1,300 sisters. Today there are 800, and the average age is sixty-nine. At age seventy-five she says, “I’m on the young half.” From the beginning, her work has been with troubled children. She wears her blue habit and veil, and lives very modestly with a group of sisters in Brooklyn, getting up at 5:30 to begin the day with common prayer. Soon she will be moving to the community’s house in Albany, New York, situated beside the cemetery where she expects to be buried. But she still has projects in mind, related, of course, to caring for kids in trouble. “I look back on my life and wish I had been holier,” she says. “I wish I hadn’t fallen asleep at prayers. I wish I had kept all my promises to people. I make more promises than I keep. I wish I could have a wand and mend a child’s broken heart.” Don’t dare mention the idea to her, but it would be no surprise if the time comes when her cause is submitted to the Congregation for Saints.

• It must be twenty years ago that the “church growth movement” was the big new thing in American Protestantism. It’s not so new anymore, but it goes on and on. Writing in Nicotine Theological Journal–which describes itself as “Dedicated to Reformed [meaning Calvinist] Faith and Practice” — Brian Pieters takes note of current evangelical books claiming that “the age of the Church is over.” The message is that Semper Reformanda, understood as perpetual change, is the imperative for survival-oriented spiritualities devoted to becoming rather than being, and so forth. The Protestant Church as we have known it is doomed to the fate of the dinosaur. Pieters writes: “Reading these words prompts one to wonder: whoever claimed that evangelicals don’t believe in evolution? These people are the veriest of Darwinists, only they have cut it out of their biology texts and pasted it into their church growth books. Really, it’s all there: dinosaurs, a hostile environment, muting genes, and natural selection (i.e., seekers). Indeed there seems no more firmly held and shared conviction about the Church today than the theory of evolution. Pick up any church growth manual today, and if you are sturdy enough to wade through some bizarre neologisms, you are bound eventually to wind up with this impassioned plea: Change or die! ” Pieters ponders this from a new book titled ‘A’ is for Abductive: The Language of the Emerging Church: “The formula that opens many mysteries of the spiritual universe is e=mc. E equals the energy of a spiritual awakening. M equals the mass density of knowledge about the Word and world that has become wisdom. C cubed is the constant of the J-factor [editors’ note: the J-factor is Jesus, we think], which is raised to three dimensions: the depth of trusting faith, the height of connectivity, and the breadth of mission. Every spiritual awakening in Christian history has been the development of this spiritual formula.” The authors drive their point home with the three-letter acronym, “COD.” Yes, it means, Change or die! But then, it’s about what one might expect when Jesus Christ, the same yesterday, today, and forever, evolves into the J-factor.

• Will those conservatives never stop? Yes, here is another “Volume 1, Number 1.” It is called Family Policy Review, is published by the Family Research Council, and is not just for policy makers. The first issue combines scholarship and readability in addressing a host of questions, with particular attention to how tax law affects marriage and family life. There is also William Saunders’ perceptive review of Hadley Arkes’ Natural Rights and the Right to Choose, to which too much attention cannot be paid. Saunders understands the significance of Arkes’ relentless work on behalf of the Born-Alive Infants Protection Act and, more comprehensively, his argument for “natural rights.” Saunders writes: “In asserting a ‘right to choose,’ abortion proponents undermine the concept of natural right, for they deny a nature that transcends the preferences of others. Law is thus reduced to power: it secures the ‘right’ of the powerful to define who has rights, even to define who is ‘human.’ It can no more be ‘contained’ than could a ‘right to own slaves.’ It will seep into areas of care of the elderly, the infirm, the handicapped. It has already poisoned the policy discussion where the status of the embryo (prior to implantation, especially) is at stake. By reducing rights to a mere reflection of the preferences of the powerful, a ‘right to choose’ puts all rights, even those claimed by abortion proponents, at risk, because such rights are always subject to redefinition when power shifts. As we confront and ponder the thirtieth year since Roe and Doe, Natural Rights and the Right to Choose offers us a way out of this blind alley. It points us to a ‘rights theory’ that is grounded not in power, but in principle. In the national debate about abortion that we must hope will follow passage of the Born-Alive Infants Protection Act, this book provides welcome direction.” For more information about Family Policy Review, contact the Family Research Council at 801 G Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20101 (www.frc.org).

• Amitai Etzioni, sociologist at George Washington University and founder of the “communitarian movement,” has brought out his memoirs, My Brother’s Keeper: A Memoir and a Message (Rowman & Littlefield, 488 pp., $35). Etzioni is an intellectual entrepreneur of remarkable energy and daunting self-confidence. From the beginning, he jealously guarded and effusively advertised his proprietorship of “the movement.” Communitarianism claimed to “leap-frog” the polarities between left and right, thus putting it in the category of the perennial “beyondisms” that typically tilt to the left. Whether or not the movement exercised the influence that Etzioni claims for it–and whether or not, for that matter, it ever was a movement—the basic idea of countering excessive individualism and balancing rights with responsibilities was sound enough. Such countering and balancing will always be necessary. Following through on my earlier work with Peter Berger on “mediating institutions” in social policy, I was an early supporter of Etzioni’s effort to turn the argument into a movement. It soon became evident. however, that Etzioni’s beyondism meant that the effort would remain safely distanced from the specific policy disputes, and not only those related to the abortion controversy, that define the cultural and political conflicts of greatest consequence. Etzioni deserves credit for trying to temper the excesses of liberal individualism, but the communitarian movement—if that is what it was–was more a matter of general disposition exemplified by a personality than a force of intellectual, never mind policy, change in America. Whether, as Etzioni claims, it was a major influence in the development of New Labor in Britain is for others to judge. Making allowances for inflated claims of importance—a problem endemic to the writing of memoirs–My Brother’s Keeper can be read as a valuable sociological and psychological case study in the quest of intellectuals for public policy relevance in the last part of the twentieth century. More than most in the company of “public intellectuals,” Amitai Etzioni championed respect for the wisdom of ordinary Americans, their traditions and habits of decency. If he was overly zealous in protecting the movement and his ownership of it by staying clear of the hard questions, there is no doubt in my mind that “communitarianism” was and is, on balance, a force for good in our public life.

• You don’t have to be Catholic to have a clergy crisis. Jack Wertheimer of Jewish Theological Seminary writes in Commentary about “The Rabbi Crisis.” The decline in vocations to the priesthood is much discussed. Less well known is the sharp decline in seminarians intending to go into pastoral ministry in the oldline Protestant denominations. Seminarians are much older, in some schools women are in the majority, with a high incidence of divorce, lesbianism, and other factors that were once considered disqualifying. With particular reference to the rabbinate, Wertheimer notes trends contributing to the diminished appeal of the religious calling: “Several other developments contributed to the erosion of the rabbis’ status. One was the society-wide assault on authority, of which many rabbis were simultaneously victims and initiators. Catering to the newly modish disdain for formality, rabbis refashioned themselves, trading in their suits for leisure wear, abandoning the title ‘Rabbi Cohen’ for ‘Rabbi Bob,’ and dropping formal sermons in favor of free-flowing discussion that might include an exchange of views with congregants. More critically still, many relinquished their roles as authorities in matters of Jewish religious law; to quote Daniel Jeremy Silver… by the mid-1980s, rabbis were making ‘a virtue of being nonjudgmental.’ A blow from a different direction came with the growth of Jewish studies in colleges and universities around the country. In a matter of decades, a whole new cadre of professionals had begun to compete with congregational rabbis as certified interpreters of Jewish texts and culture. In this competition, the title of professor inevitably outranked that of rabbi. To add to the discomfort, younger Jews joining synagogues did not share their parents’ and grandparents’ awe of the rabbi’s learning. Many of them boasted advanced degrees of their own, and felt no need for anyone to mediate between themselves and ‘the mysteries’ of Western culture.” So what might be done? You don’t have to be Jewish to recognize the applicability of his answer, mutatis mutandis, to other communities. “Rejecting defeatist advice from among their own colleagues, they would need to gird themselves to combat the present solipsistic moment in American Judaism, reeducating their congregants to think beyond their immediate personal need, their inchoate yearnings for spirituality,’ and their consumerist notion of religious life. They would need to insist on synagogue ritual focused on communal rather than privatized concerns, and they would need to reorient the synagogue itself as an institution focused on the transcendent needs of the Jewish people. Above all, they would need to take their own role seriously, accepting the burden and the challenge of their calling as individuals who speak with authority not only for themselves but for the Jewish tradition, the Jewish people, and God.”

• Bishop Joseph Sprague heads the Northern Illinois Conference of the 8.3 million-member United Methodist Church. He has, according to those who follow these matters, denied the deity of Christ, the bodily resurrection, the virgin birth, and the atonement. The conference, meeting in June, expressed its deep concern. In fact, it expressed many concerns. What were described as “prophetic” resolutions endorsed boycotts of Tyson’s chickens, Kraft macaroni and cheese, and supported the territorial demands of the Palestinians, the land mines treaty, the forswearing of military force against North Korea, increased government efforts to combat global warming, and gay and lesbian relationships as an “expression of God’s love.” The resolution on the last item urged clergy and Sunday School teachers to “tell it to our children.” The concerns about Bishop Sprague were not overlooked. A resolution was resoundingly approved supporting his ministry. Among United Methodist conferences, Northern Illinois is contending for the lead in membership decline. From mainline to oldine to sideline to oblivion.

• The Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice (RCRC) is an odd organization. Its members include oldline Protestant groups such as the Episcopal, United Methodist, Presbyterian (USA), and United Church of Christ, as well as a number of Jewish and humanist organizations. Its money (about $4 million per year) comes from outfits such as the Ford Foundation. Its focus is on young people and African-Americans. Its purpose is to promote the idea that abortion, including partial-birth abortion, is not sometimes a tragic necessity, as its member churches say, but is a “holy work,” and the defense of the unlimited abortion license is, according to RCRC, a holy war. Young people are taught that abortion is a rite of passage to adulthood, and their parents have no right to interfere with their “reproductive choice.” In short, RCRC is about as extremist as pro-abortion agitation gets. Now Michael J. Groman and Ann Loar Brooks have written a little book, Holy Abortion?, calling all this to the attention of the oldline churches. The purpose of the book is not to convert people to the pro-life position, although that would no doubt be welcome. The purpose is to call these communities to get serious about their own moral and spiritual integrity. As the authors demonstrate, the teachings of these churches are clearly contradicted by the positions advanced by RCRC. Holy Abortion? is a simple but compelling appeal for honesty. Perhaps because its bills are being footed by pro-abortion foundations such as Ford, some churches aren’t paying attention to what RCRC is doing and saying. They should. It is being said and done in their name. The book is available from wipfandstock Publishers, 199 West 8th Ave., Suite 3, Eugene, Oregon 97401 e-mail orders: orders@wipfandstock.com).

• Pondering the long reaches of history is conducive to modesty, or at least it should be. What any of us does is such a small part of the whole. Many years ago, when A. M. Rosenthal was executive editor of the New York Times, I raised a small question of religious nomenclature which resulted in a change in the paper’s style manual. Mr. Rosenthal wrote me a long letter explaining the change and concluded, “You may have the satisfaction of knowing that, in a small but important way, you have changed history.” Just think of what that implies about the historical significance of the Times, and of Mr. Rosenthal. I don’t think I’ll have his tribute inscribed on my tomb-stone. In the fourth century, St. John Chrysostom, still celebrated today as one of the Church’s greatest theologian-preachers, wrote that preachers should cultivate the virtue of “contempt for praise.” I have not yet mastered that, but am sure he was right. It does not mean that one doesn’t appreciate the nice things people say, but one does not preach—or write, or do anything else of consequence–for the sake of the nice things people may say. I have always found fetching one aspect of the “triumph” that the Roman senate would vote for victorious generals. The chariot, drawn by four horses, was wreathed in laurel, and the triumphator was attired like the Capitoline Jupiter in robes of purple and gold. At the head of the procession were the members of the senate, followed by a host of trumpeters, and then the spoils of war, the animal victims destined for ritual sacrifice, and, finally, in chains, the prisoners of the defeated army. In the chariot was a slave who held over the general’s head the golden crown of Jupiter and all along the route whispered into his ear, “You, too, are mortal.” That’s a nice touch. I do not know, but am told by those who claim to know, that in his home the great twentieth-century Swiss theologian Karl Barth had on his staircase wall portraits of Christian thinkers, beginning with Paul and Origen and moving on up through Augustine, Abelard, Bernard, Thomas, Schleiermacher, and other worthies. At the very top was a portrait of Karl Barth. The man had a sense of his place in history. It is not pride, or at least not necessarily so. A friend who is a distinguished philosopher and has had his share of triumphs tells me in a matter-of-fact manner, without a hint of boasting, that a thousand years from now or as long as philosophy is seriously done, “Nobody will be able to bypass my work.” I’m profoundly skeptical about such a claim. It’s true that we all matter, and matter ultimately. After all, we are assured that even every sparrow that falls is counted, but it is best to count on God alone to do the counting. These reflections on mortality and our part in the world’s story are prompted by my reading the entry on Beethoven in the 1960 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica I keep at the cottage in Quebec. That’s what I read in the mornings over coffee where I am spared the distraction of newspapers. The long entry is written by the long forgotten Sir Donald Francis Tovey, Professor of Music at the University of Edinburgh, who obviously had a deficient appreciation of Bach. The article ends with this: “It is as certain as anything in the history of art that there will never be a time when Beethoven’s work does not occupy the central place in a sound musical mind. When Beethoven is out of fashion, that is because people are afraid of drama and of sublime emotions. And that amounts merely to a fear of life.” So there. As the general said to the slave, “Hold the crown steady, and stop that ridiculous whispering.”

• Here are more Readers of first things (ROFTERS) who are interested in convening discussion circles. If you would like to join an FT discussion group and live in or around the following addresses, please contact the organizers. If you would like to start a group in your area, please send us your contact information.

Those living in or around Whidbey Island, Washington, can contact:

Fred and Carol Olson

P.O. Box 138

Langley, Washington 98260

Phone: (360) 579-4350

e-mail: skylark@whidbey.com

And in East Wenatchee, Washington:

Loraine Rathman, Ph.D

1614 North Astor Court

East Wenatchee, Washington 98802

Phone: (509) 884-3697

e-mail: drloraine@aol.com

If you live near South Bend, Indiana, contact:

Marian Crowe

Phone: (574) 272-3426

e-mail: crowe.11@nd.edu

or

Sidney Blanchet Ruth

Phone: (574) 234-3376

e-mail: sidneybr@att.net

In Baltimore, Maryland, get in touch with:

G. Edward Dickey, Ph.D.

Three Stratford Road

Baltimore, Maryland 21218 e-mail: gdickey@loyola.edu

In Baraboo, Wisconsin, you can contact Barbara Connolly at:

320 10th St.

Baraboo, Wisconsin 53913

In Albuquerque, New Mexico:

Barbara Prendergast

1331 Park Ave. S. W.

#512

Albuquerque, New Mexico 87102

In Barcelona, Spain:

Miquel Mundet-I-Riera e-mail: m_mundet@hotmail.com.

In (North and West) Vancover, British Columbia:

Martin Triggs

#215-2012 Fullton Ave., N.

Vancouver, British Columbia V7P-3E3

Canada

Phone: (604) 926-6657

e-mail: mtriggs@telus.net

We are greatly heartened by the interest in forming ROFTERS discussion groups. Once again, each group is entirely independent and it is up to you to decide how you wish to proceed. Our job is limited to providing grist for your several mills. With all the heavy-duty deliberating involved, we pray you’ll also have fun.

• We will be happy to send a sample issue of this journal to people who you think are likely subscribers. Please send names and addresses to First Things, 156 Fifth Avenue, Suite 400, New York, New York 10010 (or e-mail to subscriberservices@pma-inc.net). On the other hand, if they’re ready to subscribe, call toll free 1-877-905-9920, or visit www.firstthings.com.

Sources: Secular City Redux, Lakeland quotes from The Liberation of the Laity and “Does Faith Have a Future?” Cross Currents, Spring 2002.

while we’re at it: September 11th and New Yorkers, New York Times, September 8, 2003. WCC on Hussein, IRD release, September 5, 2003. On RAEL, Religion in the News, Summer 2003. Kirsch on Holifield, New York Sun, September 10, 2003. Chretien, Mail-Star, Halifax, Nova Scotia, August 11, 2003. Bishop Dolan, Catholic Herald, September 4, 2003. Seiple on Bush, Brandywine Review of Faith & International Affairs, Spring 2003. Existential America, Weekly Standard, April 21, 2003. Covenant House, New York Times, June 20, 2003. Church Growth Movement, Nicotine Theological Journal, April 2003. Rabbi crisis, Commentary, May 2003. Bishop Sprague, IRD, June 26, 2003.

Deliver Us from Evil

In a recent New York Times article entitled “Freedom With a Side of Guilt: How Food Delivery…

Natural Law Needs Revelation

Natural law theory teaches that God embedded a teleological moral order in the world, such that things…

Letters

Glenn C. Loury makes several points with which I can’t possibly disagree (“Tucker and the Right,” January…