• “Judeo-Christian.” The American Muslim Council and some others really don’t like the term. That’s understandable. In speaking of our culture, they say we should say “Judeo-Christian-Islamic” or “Abrahamic.” The National Council of Churches has joined the movement to abandon “Judeo-Christian.” Ted Haggard of the National Association of Evangelicals has a different view. “A lot of the ideas that underpin civil liberties come from Judeo-Christian theology. What the Islamic community needs to make are positive contributions to culture and society so we can include them.” That puts it a bit bluntly, but he is, I think, on the right side of the argument. People who live in places such as Dearborn, Michigan, can tell you that many Muslims have made many contributions to our society. But there are only about two million Muslims in the country and, with few exceptions, they are newcomers to the American experiment. We must wish them well. We should not, in order to make people feel good, rewrite American history, however. The founders of the experiment thought this was, quite simply and obviously, a Christian society. “Judeo-Christian” gained currency in the last century for good reasons. One reason was undoubtedly to make the two percent of the society that is Jewish feel more secure, and their sense of insecurity was not without grounds. At a deeper and theological level, Christians have come to appreciate more fully their dependence on Judaism. Christianity is inexplicable apart from Judaism. That is in no way the case with respect to Islam, which claims to be the true revelation superseding both Judaism and Christianity. We must hope that, over time, Muslims will find in Islam the resources for affirming the constituting truths of this Judeo-Christian society and culture. Whether they do or not, they can be welcomed as full citizens along with many others from outside the Judeo-Christian orbit who do not demand that we revise our national identity by speaking of a Judeo-Christian-Buddhist-Hindu-Islamic-Agnostic-Atheist society. Judeo-Christian morality undergirds America’s welcome to people who are not Jews or Christians in a way that Islamic morality, for instance, does not support the welcoming of outsiders to countries that are dominantly Muslim. However well intended, it is no service to Muslims to encourage them to challenge the moral and cultural identity that is the basis of their welcome and security in Judeo-Christian America.

• Elaine Pagels of Princeton has another book out celebrating early Christian gnosticism. Beyond Belief is about the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas, written in the second century and much amended later, which Pagels prefers to the canonical Gospels, and especially to the Gospel of John. “One of its central messages,” Pagels says in an interview with Publishers Weekly, “is that there is divine light within each person. Reacting to Thomas’ teaching, the author of the Gospel of John has Jesus always declaring that Jesus is the only light of the world. . . . Thomas is not a specifically Christian book, if by Christianity one means believing that Jesus is the only Son of God. Thomas is not about Jesus, but about the recognition of the light within us all. In this way, Thomas has a close affinity with Jewish mysticism.” Well, at least a close affinity with about 80 percent of everything in the “Spirituality” section of Borders or Barnes & Noble. The Gospel of Thomas as celebrated by Pagels is marvelously attuned to what Harold Bloom calls in a book by that title, The American Religion, namely, gnosticism pitched to a popular and apparently inexhaustible appetite for self-flattery.

• Historian James Hitchcock of St. Louis University has some fun with the special issue of the National Catholic Reporter marking the thirtieth anniversary of Roe v. Wade. The pro-life movement, say the writers of NCR, has failed. It has failed in persuading Americans; it has failed in maintaining a civil discussion of a polarizing issue; and, above all, it has failed to follow the late Joseph Cardinal Bernardin’s “seamless garment of life” proposal which, according to NCR, means that abortion is one issue among many and, since it is outnumbered by other issues backed by pro-choice Democrats, support for pro-life Republicans is morally precluded. In fact, Bernardin intended no such relativizing of the priority of abortion. In his aforementioned book Catholicism and American Freedom, John McGreevy notes that Bernardin’s last public statement, issued four days before his death in 1996, urged the Supreme Court to recognize that “there can be no moral and legal order which tolerates the killing of innocent human life.” If Americans continue to “legitimate the taking of life as policy, one has a right to ask what lies ahead for our life together as a society.” From his deathbed, the Cardinal made clear that—however others may abuse his language about a seamless garment and a consistent ethic of life—abortion is not just one issue among others. But now back to Professor Hitchcock’s little exercise: “If the NCR were consistent it would, for example, caution the opponents of capital punishment not to be shrill, warn them that often they seem insensitive to the suffering of the families of murder victims, recall that through most of its history the Church has supported capital punishment, and discuss the complex issues of deterrence, punishment, and restitution. The editors would deride liberals for supporting Democratic politicians, such as Clinton, who support capital punishment. Opponents of capital punishment would be urged to enter into respectful dialogue with its supporters, with an aim to discovering the psychoogical and social assumptions which underlie the two sides of the debate. Approaching the issue in terms of moral absolutes would be deemed counterproductive and disruptive of civil peace, and activists would be reminded that they have failed to persuade a majority of their fellow citizens on the issue. Thus, the editors would point out, the number of people executed in the United States continues to increase, the movement is a failure, and its members should at least temporarily withdraw from the fray.” “If the NCR were consistent.” If pigs had wings.

• “Today, the United Nations is more relevant than ever.” Such was the headline of a full-page ad in the New York Times signed by nearly two hundred religious leaders. The signers of the tribute to the UN and its Secretary General Kofi Annan—and the not-so-hidden attack on George W. Bush and America’s alleged unilateralism—included no Jews. There was a sprinkling of leftward Catholics and a few Muslims and Buddhists, but it was essentially a statement by officials of mainline-oldline-sideline Protestantism, with the former and present heads of the National Council of Churches leading the list. The ad featured an inspiring observation by Hiroshi Matsumoto, president of Inner Trip Reiyukai International: “By increasing our spiritual awareness we can contribute meaningfully to global peace and harmony.” The ad was sponsored by the World Council of Religious Leaders of the Millennium World Peace Summit, which has an address in midtown. The Rev. James Park Morton, former dean of St. John the Divine Episcopal Cathedral, was on the list. Another name that might have been expected, that of the man for whom Morton had worked, was missing. The same issue of the Times carried a very long obituary in tribute to Bishop Paul Moore, who, at age eighty-three, had died the previous day. The juxtaposition of the ad and the obituary was suggestive, provoking as they did memories of a religious and cultural moment now long gone. Paul Moore and Jim Morton were among my friends way back then. When in 1972 Paul became Bishop of New York (that is how the Episcopal bishop was styled, and still is), he brought Jim from the then vibrant but now defunct Urban Institute in Chicago to be dean of the cathedral. (I was offered Jim’s position in Chicago, but that didn’t work out.) They declared their intention to transform St. John the Divine into the medieval model of the cathedral as “circus,” and transform it they did: with the exoticisms of world religions, the avant garde banalities of art and theater, and occasional flirtations with the blasphemous. St. John the Divine became the very definition of trendiness. Paul was very much in the “prophetic” mode as well. During New York’s fiscal crisis of the 1970s, he thundered from the pulpit against Wall Street’s malefactors of great wealth. Last March, shortly before his death, he preached his last sermon in the cathedral, targeting U.S. policy in Iraq. “It appears we have two types of religion here,” he said. “One is a solitary Texas politician who says, ‘I talk to Jesus and I am right.’ The other involves millions of people of all faiths who disagree.” But I couldn’t help liking Paul. Born into great wealth and social prominence, Paul’s life was the perfect model of the patrician noblesse oblige that seems to have quite disappeared from American life. Tall, rugged, a much decorated marine captain who had fought in Guadalcanal, and the father of nine children, he was about as personable as human beings can get. He had worked in the inner city of New Jersey when there was great enthusiasm for urban ministries, and while I was in the inner city of Brooklyn at a black Lutheran parish we dubbed St. John the Mundane in distinction from St. John the Divine. At the cathedral, Paul and his wife Jenny lived in relative modesty in a part of what was originally built as the bishop’s palace. He told me that J. P. Morgan was a cathedral trustee back then, and when some objected that the bishop did not really need fifty-seven rooms, Morgan put his foot down, declaring that “The bishop should live like everyone else in New York.” Paul was uneasy about his wealth, and told how, as a child, when the chauffeured limousine passed bread lines, he would hide in shame on the limousine floor. We had a sharp disagreement when, in the early seventies, Paul wrote a glowing introduction to the annual report of Planned Parenthood that set forth in great detail how much money abortion had saved the city in terms of education, welfare, crime, and keeping young predators in jail. He did not agree that this was tantamount to saying that the way to improve the city is to encourage the killing of the babies of the poor. Yet, when Jenny died and Paul married a woman who had only a tenuous relationship to the Christian teaching, he asked me to give her instructions in the faith. In view of our substantial differences, I declined. Paul had not a theological bone in his body. But, taken in all, Paul Moore was a piece of work, and we are not likely to see his kind again. Not least because the Episcopal Church, at least in New York City, will never again be what it was. The Times obituary was headed, “Episcopal Bishop Paul Moore, Jr., Dies.” Thirty years ago, the word “Episcopal” would have been omitted. Then the Times and many others viewed the Episcopal Church as “the church” in New York, despite Roman Catholicism being, then and now, about fifty times larger. Still today, elegant church architecture throughout the city testifies to the time when it was the church of the Astors, DuPonts, Morgans, Vanderbilts, Mellons, and Roosevelts. There was a piquancy in the above-mentioned ad and Paul’s obituary appearing the same day. In that final sermon in the cathedral addressing the Iraq war, Paul said, “I think it is terrifying. I believe it will lead to a terrible crack in the whole culture as we have come to know it.” The culture as Paul Moore knew it had already cracked and collapsed a long time before, and some very good things were lost with it. Our falling out could probably not have been helped, but fondly and fervently I pray that he will rest in peace.

• “All news all the time” is how a local radio station describes itself. All scandal all the time is what I don’t want this section to become. But, from time to time, someone comes up with a new insight, or a fresh perspective on what we knew. That’s the case with “Strangers in the Chancery” by sociologist Joseph E. Davis at the University of Virginia. Writing in Society, Davis takes his title from David J. Rothman’s Strangers at the Bedside, an account of how, beginning in the 1960s, medicine lost much of its moral authority. There are striking parallels with what is happening with the bishops. I doubt if Davis is right that bishops today are more “strangers” to their people than were bishops fifty years ago, but the gist of Davis’ analysis rings true. For instance: “The sexual abuse scandal is also likely to produce this indirect form of authority loss. As discussed, many of the key elements that shaped the transformation of medicine are in place: increased social distance, a broad erosion of trust, and a constituency far from compliant. Moreover, medicine and doctors were only one institution and professional group among many to see trust and deference erode and their scope of discretionary authority sharply curtailed. This pattern shows an underlying cultural logic at work in American society rooted in an a priori skepticism toward the exercise of paternalism, an emphasis on individual rights and protections, and a deep suspicion of institutions. In organizations, this logic leads toward more bureaucracy and procedural rules, collective rather than individual decision-making, and the insertion of third parties (often other authorities) to constrain the actions of authorities. This logic too is playing itself out in the sexual abuse scandal. The policies adopted by the bishops in response to the scandal are the best illustration.” Davis describes the “one strike and you’re out” policy adopted by the panicked meeting of bishops in Dallas of last year, and concludes with this: “Protecting children from abuse is the justification for the drive toward proceduralism, collective decision-making, and the curtailing of discretionary authority. This is the worthiest of reasons but it is not the only one. The Catholic bishops first addressed the sexual abuse scandal in earnest ten years ago and apparently with great success. With a few notorious exceptions, repeat offenders have long since ceased to be shuffled from parish to parish and very few cases have come to light (in distinction to the public exposure of cold cases). If, in this sense, children are already safer, then why the current drum-beating for zero tolerance and zero room for pastoral discretion? Punishing the bishops is part of the story; simply having tougher rules for the sake of tougher rules is another. While these latter reasons may make everyone feel better, they are poor reasons for increasing procedural regulation. Bureaucratic structures, after all, tend to deliver an iron cage. They stifle creativity and charisma; they are blind to ends like charity and compassion; they have no inspiring mode of discourse; they do not facilitate strong group bonds; and they do not restore trust in persons. In other words, they do not supply many of the things Catholics across the board have insisted are so badly needed. As scandal works its effects, it is not too early to consider the unintended consequences of the solutions.” Pray it is not too late.

• Here is something one doesn’t see every day. In fact, I don’t recall anything like it. John Carroll, the top editor at the Los Angeles Times, sent this memo around the newsroom: “I’m concerned about the perception—and the occasional reality—that the Times is a liberal, ‘politically correct’ newspaper. Generally speaking, this is an inaccurate view, but occasionally we prove our critics right.” He went on to criticize a story on the link between abortion and breast cancer that gave full credence to those who denied the link and scoffed at those who take it seriously. The memo concludes: “We may happen to live in a political atmosphere that is suffused with liberal values (and is unreflective of the nation as a whole), but we are not going to push a liberal agenda in the news pages of the Times. I’m no expert on abortion, but I know enough to believe that it presents a profound philosophical, religious, and scientific question, and I respect people on both sides of the debate. A newspaper that is intelligent and fair-minded will do the same.” Journalistic responsibility. It’s an idea that could catch on.

• The mischievous Forum Letter is up to it again. It reports that at a Rocky Mountain Synod meeting in Colorado Springs, Bishop Mark Hanson, head of the ELCA Lutherans, spoke on a sexuality study in which that communion is embroiled. Certainly, he said, “we’re not going to base our position with regard to homosexuality on seven passages from Scripture.” One pastor leaned over to a brother and said, “Isn’t that more than we have on the institution of the Lord’s Supper?”

• “We are 100 percent focused on protecting children,” a bishop tells me in a discussion of the Dallas “one strike and you’re out” rule. One hundred percent leaves slight time or energy for anything else. Herewith a letter sent me by a priest in New England: “I agree with you that protecting children is imperative, but I am not as convinced as you seem to be that doing so is the bishops’ collective and primary motive. I was visited recently by a sixty-eight-year-old priest who, fourteen years ago, told his bishop of a sexual indiscretion that occurred thirty-one years ago and involved a then sixteen-year-old girl. His admission was the occasion of his being prudently removed from his position as pastor of a parish. The concern expressed then was that living alone could place him, and others, at risk for engaging in inappropriate relationships. The priest accepted the conditions, attended a year-long therapy and renewal program followed by three units of Clinical Pastoral Education, and found ministry at a hospital where he worked successfully, effectively, and happily for the next thirteen years while living in a small community of supportive priests in a nearby rectory. The priests, and the hospital administration, were aware of his rather ancient transgression, and in many ways he was able to offer a perspective and experience that brought home to the other priests the fragility of the human spirit and the need for fraternal support. In the months following implementation of the reactionary Dallas policy, my friend was ordered to resign his ministry as hospital chaplain and accept early retirement. He tearfully conceded. Last month, he was instructed to move out of the rectory in which he had found support, friendship, and community over the last fourteen years. At the age of sixty-eight, thirty-one years after his indiscretion, fourteen years into his repentance and renewal, the wisdom of the bishops is now that this priest should live alone and away from the support of his brother priests. This scenario is being repeated throughout the United States, and I believe it has nothing to do with protecting children. It has everything to do with ‘risk aversion,’ a term you used to describe the response of bishops to accusations against priests. Risk aversion is a concept that is wholly antithetical to ‘the gospel of sin and grace, repentance and restoration.’”

• There will be more in these pages on N. T. Wright’s big new book, The Resurrection of the Son of God (Fortress). Wright argues the case that the historical evidence, contra Enlightenment liberalism, leaves us with no reasonable conclusion other than that what happened that Sunday morning is what the New Testament writers say happened. I mention the book now only to note that Wright has been elected Bishop of Durham. (Durham, where the Venerable Bede is entombed, is in my judgment the most impressive of the English cathedrals.) David Neff of Christianity Today observes the “providential irony” that Wright’s predecessor at Durham was David Jenkins, who caused a stir by referring to the resurrection as “a conjuring trick with bones.” The role of Providence in electing Anglican bishops is not entirely transparent, but Wright’s elevation is certainly a happy turn. And it does return Durham to its tradition of scholar-bishops such as Joseph Lightfoot, Michael Ramsey, and Ian Ramsey.

• The reviewer in America, the Jesuit magazine, really does not like Thomas Oden’s The Rebirth of Orthodoxy. It “advances a conservative and fundamentalist agenda,” says John Saliba, S.J., Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Detroit Mercy. “Oden has nothing positive to say about the World Council of Churches and the National Council of Churches” and their efforts to “further mutual understanding and reduce conflict.” Oden ignores the fact that “Christian movements that claim they are the only legitimate expression of true Christianity have tended to be intolerant and belligerent.” As though that were not bad enough, Oden “offers no guidelines as to how the Church can react to technology and globalization.” That’s the least one should be able to expect from a theological book titled The Rebirth of Orthodoxy. One might be justified in suspecting that the reviewer is no friend of the rebirth of orthodoxy.

• The summer school catalogue of the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley lists a slew of courses leading to a “Certificate in Sexuality and Religion.” A person so certified is equipped “to advance the full inclusion of LGBT [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered] people in their faith communities.” One course is “Blessing Same-Sex Unions” and is offered by Mark Jordan of Emory University. Assuming that “more and more Christian congregations will be blessing same-sex unions in the years to come,” the class will wrestle with this question: “Should LGBT Christians want their unions blessed without first reforming the present theology and practice of ‘Christian marriage’?” One conservative response to this is to say, “See, those people will never be satisfied. Try to be tolerant and bless their same-sex unions and the next thing they want is to change the meaning of marriage for everybody else.” The more interesting response, I think, is to commend them for implicitly recognizing—despite public protestations to the contrary—that blessing same-sex unions does entail a reform (i.e., revolution) in the “theology and practice of Christian marriage” (without the sneer quotes). In a similar way, there was among Catholics some years ago a fairly influential organization called the Women’s Ordination Conference. There was a big split within the organization between those who simply wanted to press for the ordination of women and those who contended that the ordination of women required a radical change in the theology and practice of priesthood. The second party is right. However much one may dissent from their purposes, those who recognize that the blessing of same-sex unions and the ordination of women are incompatible with the Church’s understanding of, respectively, marriage and priestly ministry have the better part of the argument.

• Among the books noticed in Publishers Weekly is Pagan Babies: And Other Catholic Memories by Cina Cascone. It is yet another bitter account of “the earthly purgatory” of growing up Catholic, complete with Sister Perpetua and her knuckle-thumping ruler. (The title refers to money sent to missionaries for the conversion of pagans.) That review is followed immediately by a rather favorable notice of Philip Jenkins’ The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice. I expect an editor at PW was aware of the aptness of running the notices side by side.

• There are in the world thousands upon thousands (nobody knows just how many) frozen human embryos, the “spares” of in-vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures. And there is a growing debate over “embryo rescue.” This is a question very intelligently addressed by Dr. Nicholas Tonti-Filippini of the University of Melbourne in the spring 2003 issue of the National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly. Embryo rescue involves a couple “adopting” an embryo by having it implanted in the woman’s womb. The child is brought to birth and reared as the partly natural/partly adopted child of the couple. On the face of it, this is a very pro-life thing to do, since the embryo would otherwise remain in a state of suspended development for an indeterminate period of time or would be thawed and quickly die. But there is, as I say, a very serious argument over the morality of embryo rescue. Some moralists, notably Germain Grisez and William E. May, approve, while others, such as William Smith and Tonti-Filippini are on the other side. There has been no definitive statement on the question by the Magisterium of the Church, and it is therefore a point of legitimate exploration and argument by Catholic thinkers. Without attempting to do justice to the elegance of Tonti-Filippini’s case, he recognizes the indisputably good, indeed admirable, intentions of embryo rescuers, but contends that it violates the sacramental bond of marriage in which the mutual gift of self includes the exclusion of other parties from the process of procreation. He offers other persuasive, if not conclusive, arguments, not least being the fact that embryo transfer is almost always (about 96 percent of the time) unsuccessful. It has been suggested that frozen embryos might be brought to birth by transfer to an artificial womb (ectogenesis) or to an animal of another species, such as a sheep. Tonti-Filippini writes, “Part of the intuitive rejection of the idea of ectogenesis or transpecies gestation is the thought that the developing unborn child would be denied a normal relationship to a woman, his or her mother, and that that relationship is not just biological. There is something very disturbing about a child having an animal or a machine for a birth mother.” To which, as he recognizes, the response is that the embryo would otherwise be denied birth or would die without further developing. Tonti-Filippini’s article is representative of the kind of careful moral reasoning on bioethical questions that is to be found in the National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly. I do not mean that careful moral reasoning is not to be found in other publications, but the quarterly addresses these questions within a specifically Christian and Catholic framework. Each quarterly issue is handsome and big, over two hundred pages, and the articles range widely. Also of special interest in this issue is Mary Timothy Prokes on the body as sacramental or artifact, and extended discussions of John Paul II’s “theology of the body.” The quarterly is published by the National Catholic Bioethics Center, based in Boston, and individual subscriptions are $48 ($120 for institutions). Write the National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly, P.O. Box 3000, Denville, New Jersey 07834-9772.

• Here’s more on the disputed question of “embryo adoption.” Paige Comstock Cunningham of Americans United for Life writes: “Is the embryo person or property? If a person, she cannot be bought or sold. Nor can her parents ‘give’ her away. The Thirteenth Amendment (abolishing slavery) prohibits the ownership of one person by another. If, however, the embryo is deemed to be property, he may be contracted like goods or services. Or, if the embryo is equated with human tissue, blood, or organs, she may be donated, but with no payment to the donor. Here arise the questions of who is the donor—the genetic parents or the embryo—and of the purposes for which the embryo may be donated.” The Bush Administration recently allocated $1 million in support of embryo adoption, half of which went to Snowflakes, a Christian adoption agency. There are hundreds of thousands of frozen embryos, and, to date, sixteen babies have been born as a result of the Snowflakes program. Cunningham is inclined to think that the legal system is up to making the fine distinctions that can avoid Thirteenth Amendment and other problems, but she knows that abortion advocates will fight every step of the way, viewing any legal protection for the embryo “as a stealth assault on abortion rights.” She writes: “If questions of abortion advocacy did not eclipse the picture and embryo adoption was regarded as a method for providing infertile couples with a child, then the legal and moral questions might be more helpfully addressed. As long as this is not the case, every inch of linguistic and legal ground will continue to be contested. Is the very early human being ‘pre-embryo’ or ‘child,’ ‘pre-person’ or ‘person’? Is transferring such an entity to another couple ‘donation’ or ‘adoption’? Or is it something else entirely? It is not only possible, but imperative, that the law secure the future of ‘embryo adoption’ by creating a legal environment that protects the interests of everyone involved. Whether the abortion lobby and pro-life activists can tolerate such a politically necessary compromise is yet to be seen.”

• I have written supportively of the bishops who have called for a plenary council in this country in order to put the government of the Church into a greater semblance of right order. There were three such councils in the U.S. from 1852 to 1884, but none since, and some think a council overdue. At the same time, some very thoughtful bishops have been cool to the proposal, fearing that canonical requirements on representation would turn it into something of a circus not unlike the disastrous “Call to Action” conference in Detroit in 1976. That worry is reinforced by an article by Father Francis A. Sullivan, S.J., of Boston College, “The Authority of the Diocesan Bishop in the Roman Catholic Church,” published, somewhat improbably, in Lutheran Forum. While the editors of the magazine are promoting episcopal governance for Lutherans, Fr. Sullivan makes the case for a more congregational and lay-directed form of leadership for Catholics, and he thinks a plenary council may be just the instrument for achieving that goal. He sets forth a number of canonical provisions, to which he adds his own proposals, that would greatly expand participation in a council beyond the bishops, and would also mandate greater consultation by bishops in governing their own dioceses. His depiction of a plenary council does bear a striking resemblance to Detroit 1976. If a council is not the way to go, there is still the proposal on the table that the bishops should gather by themselves for an extended period of time in a remote, perhaps monastic, setting and with no press within hearing distance in order to sort out what has gone so very wrong with their leadership of the Church and what might be done about it. It seems, however, that there is no sense of urgency about any proposal for a thorough self-examination. Now that the publicity storm generated by the scandals has passed, the dominant mood seems to be one of relief and return to business as usual. The Long Lent that began in January 2002 would, many hoped, precipitate efforts aimed at deep reform and renewal. There is little evidence of that happening. Were that to happen, it would require that bishops be more fully what they are ordained to be, pastors of local churches charged with the tasks of teaching, sanctifying, and governing. One reform that is beginning to be discussed more seriously is that large dioceses be reduced to governable size. Cardinal Law in Boston is the most notable instance, but in case after case the sex-abuse scandals—never mind scandals of doctrinal, liturgical, and sundry moral delinquencies—reveal that ordinaries of dioceses are not minding the shop. And that is frequently because a diocese is too large for the exercise of the kind of pastoral attentiveness called for in the Church’s official understanding of the episcopal office. It is recognized by those discussing the matter that the idea of reducing the size of major sees may not be popular with bishops who have attained the dignity of occupying them.

• The usual suspects beat up on Senator Rick Santorum for daring to state in public his position and that of the Catholic Church that, to put it delicately, homosexual acts are not morally unproblematic. By the time this sees print, the Supreme Court may have reversed its 1986 Bowers decision that upheld the constitutionality of state anti-sodomy laws. I am not a fan of laws that are not intended to be enforced, but it is worth noting that Santorum’s offense was no more than that he agreed with the Bowers decision. Contrary to some reports on the media brouhaha, Santorum did receive support from Catholic bishops, notably from Cardinal Bevilacqua of Philadelphia and Bishop Wuerl of Pittsburgh. Not, however, from Father Robert Drinan, S.J. More than anyone else, Fr. Drinan, beginning almost forty years ago, promoted the rationalization by which Catholic politicians claimed to be liberated from the Church’s teaching, especially on abortion. On the Santorum flap, Drinan told the Washington Post, “Catholics have no right to impose their views on others. Even if they say homosexual conduct is unfitting for a Catholic, they have no right to impose that on the nation.” catholic eye impishly wonders about Drinan’s use of “they” in talking about Catholics. Senator John Kerry got a pass when, in speaking to a pro-abortion group about judicial nominations, he said, “Litmus tests are politically motivated tests; abortion is a constitutional right. I think people who go to the Supreme Court ought to interpret the Constitution as it is interpreted, and if they have another point of view, then they’re not supporting the Constitution, which is what a judge does.” The principle would seem to be that no Supreme Court decision should ever be overturned, including Dred Scott, Plessy v. Ferguson, and, for that matter, Bowers. Kerry probably didn’t mean that. As Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson probably didn’t mean it when he said, “I would love to talk to the Pope about it.” The subject was the research use of embryonic stem cells, which Thompson approves. “I think it’s in line with Church teaching that instead of throwing valuable resources away we make use of them,” he said. In the same interview he allowed as how he had not read the recent Vatican statement, “On Some Questions Regarding the Participation of Catholics in Political Life.” I’m sure that Mr. Thompson would love to talk with the Pope, but if he’s really interested in what the Church teaches on this and other questions, he might begin by reading what the Church teaches. Or maybe the idea is that he could bring the Pope around to his point of view. Politicians tend to have a high estimate of their powers of persuasion.

• Massachusetts Bill H. 3190 would, following the lead of almost two-thirds of the states of the Union, specify that marriage is a union between a man and a woman. Father James F. Keenan of Weston Jesuit School of Theology in Cambridge, Mass., is opposed to it and so testified at a hearing on the bill. As noted earlier, Fr. Keenan has written extensively and sympathetically on gay rights, “queer” theology, and related matters. “Besides coming before you as a priest,” he told the solons, “I am here as a moral theologian. We theologians see our task in the Church as teaching and interpreting the Church’s tradition and in this sense we are somewhat like rabbis whose authority derives from an ability to teach and apply the tradition to our ordinary lives of faith.” Really? The authority of a rabbi is indeed dependent upon his personal wisdom and holiness, while with Catholic theologians there is the Magisterium that defines what the tradition is and, when necessary, authoritatively indicates its correct application to the particulars of life. Fr. Keenan’s formulation would seem to be yet another way of advancing the claim that academic theologians constitute a “parallel magisterium.” He goes on to cite a number of moral theologians who agree with him that homosexuals “retain their full range of human and civil rights because of their inherent dignity as human persons.” He names nine theologians but he could have named thousands, for that is, quite simply, the magisterial teaching of the Church. The difference is that Fr. Keenan and a few others contend that human and civil rights include the right of homosexuals to have their unions legally defined as marriage. Not only that, but he appears to believe that that is the only authentically Catholic position. “In this light, as a priest and as a moral theologian, I cannot see in any way how any one could argue for H. 3190 on any Roman Catholic traditional grounds” (emphasis added). So much for the many bishops, theologians, and priests who, in their several states and in their support for a federal marriage amendment, take the position that marriage should be legally defined as a union between a man and a woman. But Fr. Keenan did say that, as with rabbis, his authority derives from his ability. As with rabbis, one is free to consult another who is able to see what Fr. Keenan is unable to see. Even better, one might have recourse to someone who accepts the responsibility of being a teacher of what the Church teaches.

• Expanding on “The Gift of Authority,” a 1999 statement of the international Anglican-Catholic dialogue, the Anglican-Roman Catholic Consultation in the U.S. has come up with a number of proposals. It is suggested that Anglican bishops accompany Catholic bishops on their ad limina visits to the Holy See, a consultation with the Pope required of heads of dioceses every five years. It is also suggested that Episcopalians and Catholics be delegates to one another’s meetings, with full voice and participation but no vote. This would include everything from synods of bishops in Rome to the Episcopal House of Bishops in the U.S. It is an interesting set of ideas, but not without notable difficulties. For one thing, it assumes, as is customary in Anglican-Catholic dialogue, a “special relationship” that makes Anglicans closer to Roman Catholics than other Christians. That place of ecumenical priority, as is made very clear in the 1995 encyclical Ut Unum Sint (That They May be One), is held by the Orthodox, who are lacking only full communion with Rome to be in full communion with Rome. Anglicans stress that they are in apostolic succession, but the 1896 decision of Apostolicae Curae declaring that Anglican orders are “utterly null and absolutely void” is still the teaching of the Catholic Church, as recently reiterated, albeit in passing, by a statement of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. That would seem to pose a problem. A while back a Catholic archbishop attended an ecumenical meeting of Episcopal and Lutheran bishops, as well as other church leaders. An Episcopal female bishop was also present, and the archbishop was criticized by conservative Catholics for addressing her as “Bishop.” To which he responded, “She’s as much a bishop as the others are.” Apart from the question of orders, some experienced ecumenists are of the view that, with respect to theological substance, Lutherans are closer to Rome than Episcopalians. Others would extend that to evangelical Protestants, noting the unquestionable commitment of most evangelicals to the core doctrines of the Christian tradition. In any event, the singling out of Anglicans for ad limina visits and other official meetings would likely meet with vigorous protest from the Catholic Church’s other ecumenical partners. One cannot readily imagine ad limina visits as an ecumenical conference with Anglicans, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Methodists, Baptists, and a host of others, none of whom holds himself or herself accountable to the Pope. With respect to origins, however, there is an Anglican distinctive. At least for high Anglicans, the Church of England is the Catholic Church in England. That self-understanding was rudely inconvenienced by the reestablishment of the Catholic hierarchy in England in the mid-nineteenth century, and is made additionally awkward by the fact that today there are more church-going Catholics than Anglicans in England. Nonetheless, the memories and the theology of high Anglicans continues to be potent, also in the minds of the thirty-six national Anglican churches of what is today called the Anglican communion. Moreover, in England and elsewhere, Anglicans more than others in the West have maintained the appurtenances of catholicity in liturgy, ceremony, nomenclature, and ecclesial structures. Then there is the factor that, for many immigrant Catholics in this country, the Episcopal Church represented the social and cultural status of their assimilationist aspirations. That is still the case for some Catholics. So there is a lingering sense of a “special relationship,” and not only in the mind of the Anglican-Catholic Consultation. But I rather doubt that it is strong enough to move the recent suggestions from the Consultation beyond the level of interesting ideas.

• The Washington-based Institute on Religion and Democracy (IRD) has a record of provoking salutary trouble from time to time. It recently issued guidelines for creating and sustaining something like a dialogue with Muslims. The guidelines delicately suggested that it is “unhelpful” and even “dangerous” when evangelical Protestant leaders publicly declare that Islam is a “wicked religion.” Typical of one strong reaction is columnist Cal Thomas, who writes: “As chronicled in this column over several years, invective against Christians, Jews, and all other non-Muslims regarded as ‘infidels’ rains down from Islamic pulpits throughout the world. The harsh rhetoric makes reference to Koranic justifications of violent means to religious ends. These include the takeover of not only the ‘West Bank,’ but all of Israel. Why would such people negotiate with ‘infidel’ diplomats who represent ‘the great Satan’ and settle for less when they believe their God wants them to take it all?” Thomas concludes, “Christians and Jews aren’t declaring war on the world, and they are not hijacking airplanes to fly into buildings or blowing themselves up among civilians. Those who do claim their mandate is from Islam. The shoe is on the wrong foot.” Well, yes and no. There is no doubt that the overwhelming preponderance of nastiness is coming from the Muslim side, but why, by responding in kind, should Christians accommodate Muslim radicals who want a holy war? We do not need to choose between being thugs or wimps, and the IRD guidelines certainly do not advocate wimpiness. They do recognize our obligation to explore whatever truth Christians and Muslims can affirm together, our interest in avoiding an unmitigated clash of civilizations, possibly descending into religious warfare, and our responsibility as the stronger party to take the initiative in building a climate of trust—or at least of reduced distrust—in which the more sensible voices within the worlds of Islam can gain a better hearing. The IRD guidelines got it just about right, I think, and I would say that even if I were not on the board of that fine organization.

• “A lost chance for moral leadership,” is how Philip F. Lawler, Editor of Catholic World Report, describes the role of the Holy See in the debate leading up to intervention in Iraq. “The just war tradition gave the Church a means of imposing restraints on warfare. By moving away from that tradition, Church leaders undermine their own influence.” There is no doubt that some in the Vatican not only moved away from that tradition but flatly rejected it. Archbishop Renato Martino of the dicastery known as Justice and Peace, for instance, appeared to jettison 1,500 years of moral teaching by declaring, “There is no such thing as a just war.” Other Vatican officials were content to sing along with the sixties banality, “Give peace a chance.” Lawler writes, “We know what the Vatican does not want: war. But what alternative does the Holy See propose? What does the Vatican want?” The worldwide war on terrorism, writes Lawler, poses questions not adequately addressed by traditional just war formulations. To cite but one such question, “How can a nation-state respond to attacks mounted by non-governmental terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda? Is it justifiable to attack other states that support those terrorists? If so, how close must the connection be?” Lawler concludes: “Today more than ever—when the potential costs of war are so high, and threats to our civilization are so immediate—the world needs the moral guidance that the Church can provide. To abandon that effort at this crucial moment, to substitute bland and pious generalities for the judicious application of just war principles, to condemn military action without offering realistic alternative means of securing justice and peace—would be a serious abnegation of the Church’s mission to the modern world.” In recent months, curial officials have repeatedly said that the teaching of the Church is not pacifist. We knew that. But what wisdom does the Church have to offer statesmen who must make life and death decisions in a dangerously disordered world? We know that, too: centuries of the most careful reflection on the criteria of justice and injustice with respect to the use of military force. Unfortunately, that tradition was ignored or traduced in most of the statements from Rome this past year, even as it was explicitly engaged by political decision-makers here and in Britain. It is hard to disagree with the observation that we have witnessed “a lost chance for moral leadership.”

• Now this, one might think, is a welcome instance of episcopal leadership. Bishop Daniel P. Reilly of Worcester, Mass., told Holy Cross College that he would not be attending the commencement at which Chris Matthews of television’s Hardball would be giving the address and receiving an honorary degree. Matthews has publicly and repeatedly declared himself to be “pro-choice.” “I cannot,” said the Bishop, “let my presence imply support for anything less than the protection of all life at all its stages.” But then a measure of confusion enters the picture. The Boston Globe quotes the Bishop as also saying, “I am not questioning the fidelity of the College of the Holy Cross to its mission as a Catholic college or its dedication to the mission of the Catholic Church.” I’m working on this. The Bishop’s presence might imply support for something less than the Church’s teaching on the protection of human life. On the other hand, the college’s inviting Matthews to give the commencement address and awarding him an honorary degree does not raise a question about its dedication to the mission of the Catholic Church. Maybe the Church’s teaching is not part of its mission. Or maybe, when it comes to fidelity, what bishops do matters while what colleges do does not. Or maybe he means that the fidelity and dedication of the college is already so much in question that he does not see the need to mention the obvious. Or maybe, dare one say, he is trying to please everybody by boycotting the offending event and, at the same time, reassuring those responsible that he does not think it is really all that offensive. After all, those protesting the honor to Mr. Matthews are a momentary nuisance, but the bishop has to live with Holy Cross. Or maybe the statement is to be read as saying, “My attending the event would imply infidelity but your sponsoring it does not because your fidelity is not in question.” I need some help here. Instances of episcopal leadership are in such short supply that I’m reluctant to give up hope on the possibility that this was the real thing.

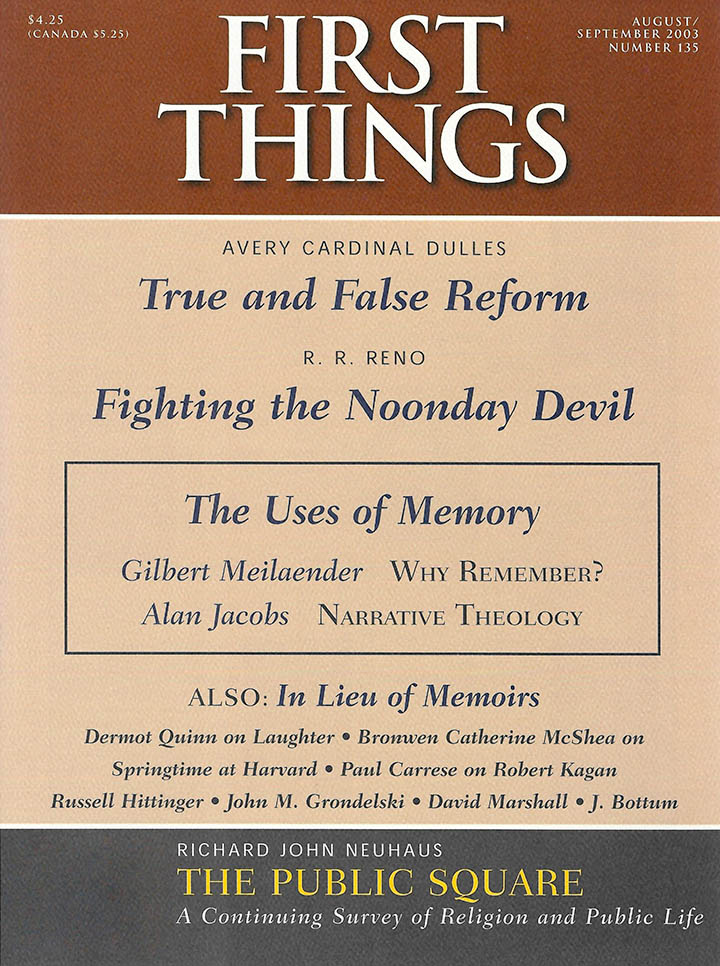

• The next issue will include an examination of the new encyclical, Ecclesia de Eucharistia, issued this past Holy Week, looking with particular interest at what it says about intercommunion between Catholics and other Christians. I will look also at some intriguing hints that Rome may be reconsidering its position that Anglican ministerial orders are null and void. And, of course, there will be commentary on new developments on the scandal front. What is this by now, “Scandal Time XV”? With Frank Keating’s resignation as chairman of the National Review Board and sharpened disagreements at the semiannual meeting of bishops in St. Louis, there would appear to be no end in sight. In addition to which, gay rights issues are rising to the boiling point in several religious communities and, as a result of court decisions, in the more encompassing culture wars. Perhaps you, too, have noticed the number of commentators who recently have taken to referring to “the culture wars of the nineties.” As though they are behind us. Dream on. And maybe there will be something worth reporting about the mood of Europe after I get back from the annual seminar in Krakow, Poland. So much happening. So little time.

• In the vast ROFTER network, some folks have established discussion groups here and there. (ROFTER, I discovered, is the Canadian acronym for “Readers of First Things.”) We regularly receive requests from people who want to start a group in their area. Sometimes we are asked to send a list of subscribers in the area, but we can’t do that since folks tend to cherish their privacy. So, since requests persist, here is what we have decided to do. If you’re interested in convening ROFTERS who want to discuss articles appearing in the journal, drop us a letter explaining what you have in mind. We will then post in this section the names and addresses of conveners, and subscribers who are interested in being part of such a group can get in touch with them. Our lawyer insists that we say such groups are not officially sponsored by FT; we are only helping to facilitate such groups at the request of readers. Let’s see how this works out.

• We will be happy to send a sample issue of this journal to people who you think are likely subscribers. Please send names and addresses to First Things, 156 Fifth Avenue, Suite 400, New York, New York 10010 (or e-mail to subscriberservices@pma-inc.net). On the other hand, if they’re ready to subscribe, call toll free 1-877-905-9920, or visit old.firstthings.com.

Sources

: Roger E. Olson on Thomas Oden’s The Rebirth of Orthodoxy, Books & Culture, May/June 2003. While We’re At It: Ted Haggard on “Judeo-Christian,” Religion Watch, June 2003. Elaine Pagels on the Gospel of Thomas, Publishers Weekly, April 14, 2003. James Hitchcock on the National Catholic Reporter, Human Life Review, Winter 2003. Journalistic responsibility at the L.A. Times, National Review Online, May 29, 2003. Bartholomew Tours, ZENIT, June 3, 2003. The ELCA on homosexuality, Forum Letter, June 2003. John Saliba, S.J., on Thomas Oden, America, April 28-May 5, 2003. On LGBT at Berkeley’s GTU, Forum Letter, May 2003. Pagan Babies, Publishers Weekly, April 14, 2003. Francis A. Sullivan, S.J., on plenary councils, Lutheran Forum, Spring 2003. Catholic politicians, catholic eye, April 30, 2003. On Anglican-Catholic dialogue, Catholic Trends, April 12, 2003. Philip F. Lawler on just war tradition at the Vatican, Catholic World Report, March 2003. Bishop Daniel Reilly and the Holy Cross commencement, Boston Globe, May 22, 2003.

Deliver Us from Evil

In a recent New York Times article entitled “Freedom With a Side of Guilt: How Food Delivery…

Natural Law Needs Revelation

Natural law theory teaches that God embedded a teleological moral order in the world, such that things…

Letters

Glenn C. Loury makes several points with which I can’t possibly disagree (“Tucker and the Right,” January…