• When I spoke at ceremonies marking the inauguration of Robert Sloan as president of Baylor University some years ago, I noted that atheist faculty members who support the idea of a Christian university are less of a problem than devout Christians who don’t (see FT, “Eleven Theses,” January 1996). It seems that is turning out to be the case at Baylor. Last May the Board of Regents fell one vote short of asking for President Sloan’s resignation, and it was rumored that he would be forced out in July. Sloan and his ambitious program “Baylor 2012”are still standing, although shaken. Baylor 2012 is based on the premise that, in Sloan’s words, “Baylor University has the opportunity to become the only major university in America, clearly centered in the Protestant traditions, to embrace the full range of academic pursuits.” Baylor, which has close to 15,000 students, has been attracting some academic superstars under Sloan’s regime. Not surprisingly, this has generated resentments among some of the faculty who liked things the way they were before Baylor aimed for the big time. Labels such as conservative and liberal get muddled here. Under the old regime, devout Bible-believing Christians operated with a “two spheres” approach to education. Science and reason were in one sphere, faith and piety in another, and there was an agreement that neither sphere would be allowed to interfere with the other. When in 1991 some Baptists demanded that their understanding of faith be in control, Baylor withdrew from the Southern Baptist General Convention. Now his opponents claim that Sloan is once again violating the truce. While for understandable reasons Sloan does not usually quote John Paul II’s 1998 encyclical Fides et Ratio, which is not recognized as authoritative by many Baptists, that is essentially the argument he makes in contending that the truce was fundamentally wrongheaded. Because the ultimate source and object of truth is one, there is finally only one sphere of truth, no matter how various the disciplines and perspectives at work within that sphere. Faculty, insists Sloan, should be encouraged to teach with an undivided mind. This is the understanding classically set forth in Michael Polanyi’s Personal Knowledge, and it is noteworthy that, when Sloan invited William Dembski to establish a major program at Baylor, it was called the Michael Polanyi Center. Dembski, famous for advancing the “intelligent design” argument against dogmatic Darwinism, ran into ferocious opposition from proponents of evolution who are defenders of the old truce. There are other complaints against Sloan, such as his allegedly heavy-handed and top-down management style, but these are the rumblings common in most faculties. The crux of the conflict at Baylor is over the nature of truth, and whether it is possible under evangelical Protestant auspices to build a world-class research university and thus provide a counterforce to the dreary history of the declension of Protestant (and Catholic) higher education from Christian seriousness, a declension powerfully narrated by James Burtchaell’s The Dying of the Light. (For a summary of Burtchaell’s thesis see FT, “The Decline and Fall of the Christian College,”June 1991.) The cultural and intellectual influence of Christian higher education in this society has a lot riding on the bold, and predictably embattled, experiment underway at Baylor.

• It’s all so unfair. According to Nancy Halpern of the Strickland Group, a New York “executive coaching organization,” the metrosexual men celebrated by the TV show “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy” are moving ahead rapidly in business. If men who cultivate their softer and feminine side are doing so well, asks Seattle Times columnist Carol Kleiman, “Why is the glass ceiling still so firmly in place for women? Why are so few women in the ‘glass elevator’ that propels men to the top?”(A glass elevator goes through a glass ceiling?) “Because,” says Halpern, “women not only are a minority, but they also get conflicting advice. For twenty years they’ve been told to be more like men—and clearly that doesn’t work.” The system works for men who are like women but not for women who are like men. One might expect Ms. Kleiman to conclude that women should be like women. But that would imply an idea, i.e., stereotype, of what it means to be womanly. It’s so, so unfair.

• It was once known as the home of the Acadians, and Longfellow immortalized the British expulsion of the French in “Evangeline.” In more recent history, people knew of Halifax, Nova Scotia, for its heroic part in World War II’s Battle of the Atlantic. But now it’s slim pickings in the struggle for cultural distinction. “Halifax is One of the World’s Capitals of Lesbian Pulp Fiction” is the heading of a full-page story in Canada’s National Post. It seems that Mount St. Vincent College in Halifax, which is described as “a small liberal arts university best known for its women’s studies programs,” has 119 titles of lesbian pulp fiction in its library. Count them: 119! With a nod to Oklahoma, everything is up to date in Halifax, they’ve gone about as fer as they can go. In Kansas City, never mind New York, I expect there are hundreds of closets stacked with more than 119 dirty books. Just think: so many world capitals of pornography. Yes but, at Mount St. Vincent “some of the books are suggested reading for the students.” Well, that is a distinction. At most schools, from Harvard to Podunk State, they are required reading, especially in women’s studies programs. But stifle your giggles, please, and remember that this is Canada, where a national paper must stretch to assure Canadians that they should not be as forgotten as they are. Oh yes, Mount St. Vincent is a nominally Catholic school; so nominal that the news story doesn’t mention it. The school is receiving no complaints about its being on the cutting edge, except for one. “You could tell he was a fairly religious, conservative person,” said librarian Meg Raven. “He said something like, ‘You are going to burn in Hell for having this material on display.’” To which the reporter has the snappy wrap-up line, “Sounds like he’d been reading Satan Was a Lesbian.” Oh, those Canadians.

• It was not “withdrawn,” it was just “not published,” insists the staff of the bishops conference (USCCB). At issue is the “Presidential Questionnaire” that the conference sends to candidates every four years. It’s a kind of checklist of candidates’ positions in comparison with those of the USCCB. Pro-life groups did not like this year’s questionnaire at all. It is, they complained, all apples and oranges. Said Austin Ruse of the Culture of Life Foundation, “It improperly equates doctrinal issues like abortion with judgment calls like the minimum wage.” In short, it was skewed in favor of a candidate who, while supporting abortion and embryonic stem-cell research, also favors a long list of items favored by the staff of the USCCB and therefore comes out as being more in agreement with Catholic teaching. The USCCB wants it understood that the questionnaire was not withdrawn because of pro-life criticism. The communications office said it “decided not to publish the results of the questionnaire because neither of the candidates responded to it before the deadline.” Perhaps it is more accurate to say that they decided not to publish the results because there were no results. On the other hand, maybe one or both candidates completed their assignments late. (Apparently Ralph Nader and the fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-party candidates were not asked.) The most likely explanation is that the Bush campaign saw the questionnaire as a booby trap, and the Kerry campaign, in one of its makeovers which included firing two “religion outreach” directors who turned out to be flaming lefties, either lost the form or decided that the less said about Kerry’s Catholicism the better. Either way, the implication is that the opinion of the USCCB is not high on the list of things requiring attention in presidential politics.

• My first contact with William F. Buckley, Jr. was many years ago when I was still viewed as a man of the left and wrote him a stiff note protesting something he had said about civil rights leaders. He wrote back, politely pointing out that I had misquoted him and inviting me to lunch. For some reason I don’t remember, that lunch didn’t come off, but in the years since then there have been many lunches, dinners, and meetings on his long-running but now discontinued show “Firing Line.”(Dinner invitations to his residence off Park Avenue direct one to “73 East 73rd Street at 7:30.” He assures me the number 73 has no occult significance.) We have disagreed on matters of substance (see, for example, While We’re At It, October), but I count Bill Buckley a dear friend and admire him as the exemplification of what it means to be a gentleman. His has been an extraordinary life of achievement and adventure: essayist, novelist, lecturer, editor, sailor, musician, candidate for mayor of New York, and the alchemist who turned a conservatism of irritated gestures into an intellectual, cultural, and political movement of great consequence. (I still have a matchbook printed with a photo that, taking off from a New York Times ad campaign in those years, has President Reagan reading Bill’s magazine under the caption, “I got my job through National Review.”) Bill is nearing eighty now and slowing down a bit, but he’s slowing down from what most mortals never dreamed of getting up to. He has now brought out Miles Gone By: A Literary Autobiography (Regnery). It’s as big (594 pages) as it is irresistible, collecting some of his best and more personal pieces and providing me hours of learning and remembering what I once knew. In his review of the book, William McGurn notes that some have criticized Bill for obsessions such as sailing and the harpsichord, to which McGurn responds: “The concern seems to be that enjoying oneself so thoroughly, at a time when So Many Serious Issues Still Threaten The Republic, violates some precept. But that is only true when measured against the nasty calculus of a utilitarian age that forgets what it means to be human. Miles Gone By is a bracing reminder of an essential conservative principle: that the state exists so that we might have private lives, not vice versa. ”I know a little less than next to nothing about sailing, but greatly admired this passage toward the end of the book: “You have shortened the sail just a little, because you want more steadiness than you get at this speed, the wind up to twenty-two, twenty-four knots, and it is late at night, and there are only two of you in the cockpit. You are moving at racing speed, parting the buttery sea as with a scalpel, and the waters roar by, themselves exuberantly subdued by your powers to command your way through them. Triumphalism . . . and the stars seem to be singing for joy.” Of that passage, McGurn writes, “You could say the same thing about the satisfaction that comes from writing a fine paragraph. Or a life that set itself, with astounding success, against most of the prevailing winds of his day.” I do not take too seriously Bill’s asseverations (as he might say) about retiring from this, that, and the other thing. He may have shortened the sail to get more steadiness, but I am among the many who count on his continuing company to alert us to the stars singing for joy.

• In Winslow Homer’s 1899 painting “The Gulf Stream,” a black sailor is trapped on a sinking boat that is surrounded by sharks. The sharks encircle the boat, writes the noted art critic Nicolai Cikovsky, “with sinuous seductiveness.” They “can be read as castrating temptresses, their mouths particularly resembling the vagina dentata, the toothed sexual organ that so forcefully expresses the male fear of female aggression.” Reviewing Roger Kimball’s The Rape of the Masters (Encounter), David Gelerntner writes: “Why would a critic write such stuff? Peer pressure, says Mr. Kimball: ‘to ensure his own place as a “brilliant” “scholar” in a “great” contemporary university.’ But he provides the raw material for a deeper explanation. A century ago, professors could regard themselves as socially superior to artists and could afford to be generous and admiring without jeopardizing their own self-regard. But modern professors can no longer pull rank on anyone. Accordingly, two mammoth projects were launched. Since the early decades of the twentieth century, intellectuals have built a case that criticism can itself be a species of literature. There is something to that. But the educated public has continued to regard great artists as geniuses and great critics as critics. Hence the remarkable follow-on project of the past thirty-odd years: cutting the geniuses down to size. Mr. Kimball quotes Professor Keith Moxley, speaking for thousands of like-minded colleagues: “‘Genius” is a socially-constructed category.’ Thus Michelangelo merely appeared to be a genius to the long-ago (pre-industrial, profoundly religious, all-but-incomprehensible) mind of sixteenth century Italy!” The title of Mr. Kimball’s book will likely arouse critical theorists to further erotic frenzies, but his brief against intellectuals who write things that only other intellectuals could believe is not exaggerated. And Mr. Gelerntner’s shot at a sociological explanation of what has brought us to our present pass is entirely plausible. “Many writers have discussed the death of authority; we ought to ponder the death of admiration too,” says Gelerntner. When critics put “genius” in sneer quotes, they are really saying, “That was then, I am now. Don’t look at what the ‘genius’ painted or wrote. Look at me!” It is not a pretty sight.

• From The Cresset, published by Valparaiso University and edited for some twelve years by our former editor, Jim Nuechterlein, Martin Marty’s Context picks up on some suggestive ponderings by William Placher, a Protestant theologian at Wabash College in Indiana. (Wabash is, I am told, one of only two all-male colleges left in the country and is the alma mater of two of our former editorial assistants, Matthew Rose and Vincent Druding.) Placher writes, “Belief in the Trinity seems as if it ought to be at the center of Christian faith.” We are baptized in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, other sacraments and sacramentals are in the same trinitarian name, and churches, colleges, and institutions beyond number are called “Trinity.” “And yet,” writes Placher. His reflection is, mutatis mutandis, as pertinent to Catholics as to Protestants, or at least to Catholics who have unreflectively internalized an individualistic American culture. Here is Placher: “And yet. My guess is that a great many of us have rarely if ever heard a sermon on the Trinity. The average contemporary preacher hopes that Trinity Sunday will come on Father’s Day or Flag Day or some occasion that provides an excuse for preaching about something else. [Theologian] Karl Rahner observed that, if the doctrine of the Trinity had to be dropped as false, most Christians today would carry on their lives pretty much as before. The Trinity may be in the printed catechism, he said, but it is not in the catechism of the heart. When the bishop and theologian Gregory of Nyssa moved to Constantinople in the fourth century, he heard debates about the Trinity on every street corner. ‘Garment sellers, moneychangers, food vendors,’ he wrote, ‘they are all at it. If you ask for change, they philosophize for you about generate and ingenerate natures. If you inquire about the price of a loaf of bread, the answer is that the Father is greater and the Son is inferior. If you speak about whether the bath is ready, they express the opinion that the Son was made out of nothing.’ . . . I don’t think I’ve ever heard an argument about the Trinity in the grocery store. Is it because we all agree? Or is it because we just don’t much care? Dorothy Sayers, theologian and writer of mystery stories, once remarked that to the average churchgoer today, the mystery of the Trinity means, ‘The Father is incomprehensible, the Son is incomprehensible, and the whole thing is incomprehensible. Something put in by theologians to make it more difficult—nothing to do with daily life or ethics.’ . . . One of the things that philosophers and psychologists teach us is that we exist as persons only in relation. A Robinson Crusoe or Tom Hanks confined to his island alone from infancy doesn’t become a fully human person. There’s no one with whom to interact. Likewise, if Mary is the child of a loving family and Sally is the product of an abusive home, there is not in either case some core identity of who they really are [that is] unaffected by environment. If you get up in the morning—don’t try this at home, as they used to say on TV—and everyone you meet looks at you with puzzled concern and says, ‘Are you feeling OK?’ you’ll be queasy by lunchtime. For good or ill, we become who we are in relation with others. That relations so shape our identities constitutes a central element of what makes us persons. A rock isn’t a person, because a rock is what it is whether there’s another rock next to it or not. But we’re different. We’re persons because our relations contribute to the constitution of our identities. Human sin pushes us to think of ourselves in radically individualistic terms, and our society is particularly inclined toward individualism. We Americans, if our ancestors were not Native Americans or slaves forced here against their will, are generally the descendants of people who didn’t fit in, who weren’t comfortable with the communities in which they lived, who were willing to go off and start up by themselves. Their genes are in us, and they provide us with many virtues, but they can also make us remarkably self-centered. To steal an old joke, the most popular picture magazine used to be one called Life. All of life. That was succeeded by People. Not all of life, but at least all people. Then People was challenged on the newsstands by Us. Not even all people—just us. And now I see on the newsstand a magazine called Self. I can’t think where we could go from here. A lot of social forces contribute to our self-centeredness. Still, I wonder if a misguided philosophy of what it is to be a person doesn’t play at least a small role. I think that I, by myself, define my essential identity and that everything else—my friendships, my obligations, my relation to my environment—is all secondary to who I really am. Such an assumption about who a person is slides easily into the ethical conviction that how I treat the rest of you isn’t nearly as important as the care and feeding of me. The doctrine of the Trinity, by contrast, reminds us that persons are essentially in relation. Our relations aren’t an ‘add-on,’ they’re at the core of who we are. To the extent that this isn’t true for human persons, it’s a sign of our failure to be persons in the fullest sense, after the model of the divine persons.”

• Older physicians, according to a recent medical journal report, are more likely than younger physicians to prepare advance directives for how they want to be treated if they are incapacitated, but they are much more skeptical about whether such directives will have a significant bearing on the treatment they actually receive. They know from experience. I suppose there is no surprise in their being more likely to prepare directives since, being older, they have more occasion to think about the end of life. It turns out, however, that their skepticism about how they will, in fact, be treated is fully warranted. This study reports that doctors, whether older or younger, do not follow advance directives in 65 percent of cases. It turns out that other factors, such as prognosis, perceived “quality of life,” and the wishes of family and friends, are much more determinative of treatment. All in all, the study is reassuring. To be surrounded by family and friends who genuinely care for you is an irreplaceable blessing. Advance directives assume a knowledge of contingencies and complexities that cannot be foreseen. As important, when we are in the fullness of health, it is too easy to say there are conditions under which we would no longer want to live. As I wrote in As I Lay Dying, a personal account of having been there, one discovers that a circumstance that others may view as “worse than death” is vibrant with life. That is something one learns only when it happens. Advance directives written in the absence of advance knowledge provide very uncertain guidance. The study prompted me to go back and read again our Ramsey Colloquium statement, “Always to Care, Never to Kill.” It stands up very well, and you might want to check it out on the website (old.firstthings.com).

• Time magazine and others did some heavy breathing about deep cultural change in reporting that, from 1993 to 2002, the number of Americans identifying themselves as Protestant dropped from 63 percent to 52 percent. The number identifying themselves as Catholic remains stable while “other”—Eastern Orthodox, Muslim, and sundry Eastern religions—has increased from three to seven percent. I’m not sure about the significance of the decline in those identifying themselves as Protestant. Many who used to call themselves Protestant now prefer to be known simply as Christian. The term Protestant always had an unecumenical over-againstness about it, meaning chiefly that one is not a Catholic. Over the last decade, and for many reasons, Protestants have felt less urgency about making a point of their not being Catholic. Witness the generally positive response to Evangelicals and Catholics Together, launched in 1994. Plus, many of the large non-Catholic “megachurches” studiously eschew denominational labels of any sort, and “Protestant”is often viewed as such a label. My hunch is that the survey, conducted by the National Opinion Research Center, says something interesting about changing Protestant attitudes toward Catholicism, and about the anti-denominational and anti-institutional character of religion in America, which remains emphatically Protestant.

• I don’t know how many times, perhaps three or four, I have referred to Father Andrew Greeley in these pages. My usual point is to acknowledge his longstanding contributions when he sticks to what he knows as a sociologist, and especially when he criticizes secularization theorists opining on the inexorable decline of religion. Each time I make a favorable mention, however, I receive protests from readers who wonder how I can be so nice to a man who is so outrageously wrongheaded on a thousand other subjects. Part of the answer, of course, is my famously irrepressible niceness. For readers who fear that I am uninformed about “the real Andrew Greeley,” herewith an excerpt from a recent column of his in the Chicago Sun-Times on President Bush. “He is not another Hitler. Yet there is a certain parallelism. They have in common a demagogic appeal to the worst side of a country’s heritage in a crisis. Bush is doubtless sincere in his vision of what is best for America. So too was Hitler. The crew around the President—Donald Rumsfeld, John Ashcroft, Karl Rove, the ‘neo-cons’ like Paul Wolfowitz—are not as crazy perhaps as Himmler and Goering and Goebbels. Yet like them, they are practitioners of the Big Lie—weapons of mass destruction, Iraq democracy, only a few ‘bad apples.’ Hitler’s war was quantitatively different from the Iraq war, but qualitatively both were foolish, self-destructive, and criminally unjust. This is a time of great peril in American history because a phony patriotism and an America-worshipping religion threaten the authentic American genius of tolerance and respect for other people. The strongest criticism that the administration levels at Senator John Kerry is that he changes his mind. In fact, instead of a President who claims an infallibility that exceeds that of the pope, America would be much better off with a President who, like John F. Kennedy, is honest enough to admit mistakes and secure enough to change his mind.” George W. Bush as Adolf Hitler? A reader asks how Fr. Greeley can still be a priest in good standing. That is a question best addressed to the Archbishop of Chicago, but I expect his answer would be that, if he kicked out every priest who is a political nut case, there would be a lot of empty altars in Chicago. The problem is not unique to Chicago, although it is no small blessing that Fr. Andrew Greeley is.

• It was my first visit to Australia. Invited by George Cardinal Pell, the engagingly orthodox archbishop of Sydney, to give a series of lectures in Sydney and Melbourne, I received a most positive impression of the place. Upon my return, I read an article on Australia that lamented the “cultural cringe” to which Australians are prone. It did not seem that way to me. But that may be because I could not help but draw comparisons with Canada, where I was born and reared. When I was a schoolboy we all took considerable pride in the classroom maps that depicted one quarter of the world in the pink of the British Empire, of which Australia was very much part. To my young mind, the Empire and the King (later, the Queen) were ever so much more impressive than “the States” where there was a President named Truman (later, Eisenhower). Since Pierre Trudeau & Co. declared that Canadian history began with the adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, Canada has been in a cultural cringe much more pronounced than anything I detected in Australia. Of course, Canada had the problem of being two nations, French and English, with the English clearly dominant, and some argue that there was no alternative to Trudeau’s way of resolving the problem. But the dropping of the British identity gave birth to the dominant—sometimes it seems the only—public discussion in what continues to be two nations: What constitutes Canadian identity? And that discussion turns, with wearying repetition, on the ways in which Canadians are not like Americans. Australians, by way of contrast, seem much more confident about who they are. They are, among other things, decidedly pro-American. Perhaps that would be different if, like the Canadians, they lived side-by-side with the U.S., with 80 percent of their population living within a hundred miles of the U.S. border. In Australia it is said that they will not let their geography defeat their history. Theirs is a huge British island, with a small aboriginal minority, in a huge Asian sea. Canada has a much more respectable European history, with distinguished French components, but Australia seems much more comfortable with its history, which is based in its being a British penal colony in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. That is no doubt one reason why they have, again just recently, decided to maintain connections with the Queen. Although I might mention that Cardinal Pell is a strong and public proponent of republicanism, which he believes would increase confidence in Australian identity. Perhaps he is right about that. We met with parliamentarians in Canberra, the nation’s capital, and afterwards sat in on “question period” in which members baited the prime minister, John Howard, who seemed to relish the ordeal. I noted that Parliament was opened by the Speaker’s leading the body in reciting the Lord’s Prayer. Very unlike America, although not so unlike what Americans might think appropriate were it not for “the separation of church and state.” Very, very unlike Canada in its determination to be unlike America. Don’t get me wrong. I love Canada, and try to spend some time there each summer at the family cottage in Quebec. But I could not help making comparisons with Australia, and decidedly to Australia’s advantage on some scores. I hope I get invited back to Australia. And that the Canadians will still let me in.

• When the Catholic Church says something is a “scandal,” the reference is not to bad publicity but to endangering the souls of others. Here’s the official definition: “Scandal is an attitude or behavior which leads another to do evil. The person who gives scandal becomes his neighbor’s tempter. He damages virtue and integrity; he may even draw his brother into spiritual death. Scandal is a grave offense if by deed or omission another is deliberately led into a grave offense”(Catechism A4 2284). Hence the concern about politicians who publicly and persistently support the abortion license. But what about nuns? Twenty years ago, on Respect Life Sunday, twenty-six nuns signed a full-page ad in the New York Times declaring that there is more than one authentically Catholic position on abortion. The Vatican got on the case and notified their superiors that the nuns must retract or face expulsion from their orders. Dominican Sister Donna Quinn was one of the signers. Twenty years later she says, “We held firm. The Vatican backed off actually, but they’ll never admit it.” Quinn, along with four other nuns, marched in last April’s raucous “March for Women’s Lives” in Washington. Ann Carey of Our Sunday Visitor notes also that the National Coalition of American Nuns gave its “national medal of honor” to Francis Kissling, founder of Catholics for Free Choice. Ms. Carey is puzzled that these nuns seem to have an untroubled relationship with their orders and with the Church at a time when bishops are trying to clarify the meaning of communio and Communion. Ms. Carey is not alone.

• Father Michael Prior, author of Zionism and the State of Israel: A Moral Inquiry, was a main speaker this spring at a conference of six hundred people, one half from the U.S., sponsored by the Sabeel Ecumenical Liberation Theology Center and held at the Notre Dame Center in Jerusalem. The conferees met with Palestinian President Yasser Arafat in his Ramallah compound, and he thanked them for their efforts to counter Christian support for Israel in the U.S. The title of the conference was “Challenging Christian Zionism: Theology, Politics, and the Palestine-Israel Conflict.” Fr. Prior attacked churches and Bible scholars who “buy in very comfortably to the biblical narrative that allows legitimacy to preferential treatment on the part of God in favor of one people, that not only legitimizes but actually mandates genocide.” The Book of Exodus, “which we read with great piety, is actually a con job.” The authors of these biblical stories, he continued, “were narrow-minded, xenophobic, militaristic, pin-headed bigots.” Joshua, who led the occupation of Canaan, is “the patron saint of ethnic cleansing.” Shortly after his return to the U.S., Fr. Prior was hit by a massive heart attack and died. Christian Zionists discern the hand of YHWH. They would, wouldn’t they?

• Survey research and common sense combine in telling us that children tend to share the values of their parents, including their political views and way of life. It is far from the most important factor in abortion, but there are enormous political consequences in the forty million children aborted since the infamous Roe v. Wade decision of 1973. In the June issue of the American Spectator, policy wonk Larry Eastland does the number crunching on “missing voters.” “There were 12,274,368 in the Voting Age Population of 205,815,000 missing from the 2000 presidential election, because of abortions from 1973–82. In this year’s election, there will be 18,336,576 in the Voting Age Population missing because of abortions between 1973 and 1986. In the 2008 election, 24,408,960 in the Voting Age Population will be missing because of abortions between 1973–90.” Moreover, according to a major survey by Wirthlin Worldwide, Democrats account for 40 percent more abortions than Republicans (49 percent versus 35 percent). Statistically, the more liberal Democrats are, the more abortions they have; the more conservative Republicans are, the fewer abortions. Eastland writes, “Examining these results through a partisan political lens, the Democrats have given the Republicans a decided advantage in electoral politics, one that grows with each election. Moreover, it is an advantage that they can never regain. Even if abortion were declared illegal today, and every single person complied with the decision, the advantage would continue to grow until the 2020 election, and would stay at that level throughout the voting lifetime of most Americans living today.” Given the partisan distribution of “missing voters” as a result of abortion, says Eastland, in the 2000 election Gore would have won Florida by 45,366 votes instead of Bush winning by 537. The abortion factor powerfully affects not only presidential elections but also congressional elections in the most crucial swing states. Eastland concludes: “As liberals and Democrats fervently seek new voters and supporters through events, fundraisers, direct mail, and every other form of communication available, they achieve results minuscule in comparison to the loss of voters they suffer from their own abortion policies. It is a grim irony lost on them, for which they will pay dearly in elections to come.” I’m not vouching for Eastland’s argument. I suspect there are variables not taken into account. But it does seem blindingly obvious: killing your offspring is not a good way to multiply your kind. As I say, this is very far from being the most important consideration regarding abortion, but it is not uninteresting. It should not be necessary to say that, whatever gratification conservatives may draw from the working of a rough justice suggested by these statistics, they must not forget that being pro-life means being pro-life also with respect to the children of those who aren’t.

• All in all, Adam Kirsch, book editor of the New York Sun, seems to want to like Gertrude Himmelfarb’s new book, The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments (Knopf, 284 pages, $25). He says nice things about her argument that intellectual elites have been strongly biased in favor of the French version of enlightenment, including this: “Such elitism helps to explain the philosophes’ enthusiasm for enlightened despots, and their lack of interest in political liberty. This marks the central difference between France and America. The America Founders, she writes, devised a Constitution based not on pure reason but on practical checks and balances; they did not theorize about the best imaginable government, but actually created the best possible one. They even managed to make liberty and religion mutual allies, to the surprise of Tocqueville: ‘Among us,’ he wrote, ‘I had seen the spirit of religion and the spirit of freedom almost always move in contrary directions. Here I found them united intimately with one another.’” But then there is Kirsch’s remarkable caveat that Professor Himmelfarb fails to appreciate that British “benevolence” masked an increasingly rapacious capitalism, “while Voltaire and Diderot showed greater moral courage in confronting religious questions than did the rather evasive [Adam] Smith.” A good Straussian may here discern the influence of Leo Strauss. Were he not so evasive (read cowardly) Smith might have joined Voltaire in crying, “écrasez l’infame!” The infamous thing, of course, was Christianity, and the Catholic Church in particular, although the cleverly obnoxious Voltaire used the phrase also in connection with other irrationalities, an irrationality being any idea or practice of which he disapproved. Mr. Kirsch does restrain himself from suggesting that Tocqueville was also evasively “writing between the lines” against religion’s dolorous influence on American democracy. He ends up with the evasive observation that the book “is meant to start debates, not to settle them; in that purpose, Ms. Himmelfarb succeeds admirably.” No, Prof. Himmelfarb clearly wants to settle the debate about the relative merits of eighteenth-century enlightenments, and Mr. Kirsch just as clearly disagrees. One has to wonder what oppressive regime—unless it is the conservative Sun’s friendly disposition toward Gertrude Himmelfarb—compels him to write with such Straussian indirection.

• “One-size-fits-all solutions are often inadequate. We must renew our efforts to ensure that the punishment fits the crime. Therefore we do not support mandatory sentencing that replaces judges’ assessments with rigid formulations. . . . Finally, we must welcome ex-offenders back into society as full participating members, to the extent feasible.” Thus spake the U.S. bishops in a November 2000 document on the American criminal justice system, “Responsibility and Rehabilitation.” Less than two years later, meeting at Dallas in June 2002, they took it all back, at least insofar as the teaching applies to priests accused of sexual abuse with minors. The “essential norms” hastily adopted at Dallas come up for review by Rome this December. There is every reason to believe that review will be informed by “Rights of Accused Priests,” a recent article by Avery Cardinal Dulles in America. The “zero tolerance” policy of Dallas, he writes, is in fifteen ways unjust, unwise, or in violation of church law and Christian morality, or all of these combined. Most of the points made by Dulles have received repeated attention in these pages. They include the denial of a presumption of innocence and due process, a definition of sex abuse so malleable as to mean almost anything, an abandonment of proportionality between offense and punishment, an abdication of the episcopal duty of judgment, betrayals of confidentiality, the “forced laicization” of priests contrary to the doctrine of priestly consecration, and other actions reflecting “an attitude of vindictiveness to which the Church should not yield.” I expect my favorable mention of Dulles’ article will again produce protests that he and I are “soft” on sexual abuse. Nonsense. There must be zero tolerance of crime. The punishment of the innocent and the demonstrably reformed sinner who poses no credible threat to anyone is itself another crime. The denial of the power of conversion is a denial of the Church’s very reason for being. The Dallas document quoted from the Pope’s address to American cardinals in April 2002: “There is no place in the priesthood or religious life for those who would harm the young.” Nobody should deny that, but the document omitted what the Pope also said: “At the same time, we cannot forget the power of Christian conversion, that radical decision to turn away from sin and back to God, which reaches to the depths of a person’s soul and can work extraordinary change.” Minimally, one might expect the bishops to rise to the norms they prescribe for the criminal justice system of the secular order. In a more hopeful mode, one might even dare to look for an understanding of sin, forgiveness, conversion, and justice consonant with the gospel the Church proclaims. When it comes time for Rome to reconsider the gravely flawed norms of Dallas, the pertinent parties should have Cardinal Dulles’ checklist of necessary remedies close at hand.

• John F. Kennedy wore his Catholicism as “unselfconsciously and elegantly as he wore his London clothes,” wrote the late John Cogley, Commonweal columnist and Kennedy adviser. Icon is the word to describe Cogley’s status among “Commonweal Catholics” in the years during and immediately following the Vatican Council II. Before he died in 1976, Cogley joined the Episcopal Church, believing that there he could live a lower-case catholicism free of the cumbersome burden of authority. Many years later, commenting on John Kerry’s failure to make a plausible connection between his pro-abortion politics and Catholic faith, the current editors of Commonweal cite the above quote and offer this reflection: “Historians now tell us that Kennedy’s Catholicism was perhaps not so much unselfconscious as it was unthinking. In any event, forty-four years later the potential conflict between a President’s duty both to uphold the Constitution and to abide by Catholic teaching is perhaps even more acute. This time the divide is not over issues like the constitutionality of tax support for religious schools but the much more fundamental question of what obligations the state has to protect fetal life. The social context has also changed. Kennedy was the charismatic symbol of Catholic material success and cultural assimilation, not Catholic distinctiveness. At the dawn of a new century, Catholics are asking if assimilation has not become simple co-optation, and they increasingly wonder what must be done to preserve any distinctive Catholic practice or identity.” Catholics are indeed asking that, and many of them—including perhaps a majority of the bishops—have arrived at the answer that the “acceptance” of Catholicism represented by JFK’s election was a poisonous prize.

• Paul Holmer died this past June. Michael Linton, who writes on music in these pages, tells me that as a young man Holmer was both pianist with Dimitri Metropolis and lead piano for Mordecai Ham, a famous Baptist gospel crusader. That suggests a person with a certain cultural reach. Born in 1916, he was the son of free-church dissenters from Sweden’s establishment Lutheranism. Inspired by David Swenson of the University of Minnesota, Holmer was instrumental in introducing Søren Kierkegaard to an American audience. It was as professor of philosophical theology at Yale, however, that Holmer helped to form generations of pastors, theologians, and philosophers. Linton writes: “These are issues of the human heart and Holmer insisted that theology was a kind of therapy, or care, for the human heart. Once a discussion at the Yale Divinity School common room was devoted to the question of whether or not the institution was a ‘caring’ place. Henri Nouwen (with whom Holmer shared a deep friendship), spoke at length about the importance of ‘caring’ and a colleague seconded his remarks, at equal length. Holmer, a bit irritated, said, ‘You get the feeling we’re all a lot of hothouse plants just crying for attention. I thought that Christian caring was something specific. A doctor cares for the patient by restoring the patient’s health. The teacher cares for the student by expunging ignorance in the student. Now Christian care means helping to overcome human sinfulness by the grace of God. That’s Christian care.’ Holmer’s Christian care was to clear away confusions and to allow various capacities to be nursed and others to be starved. Students would ask Holmer what he thought was required to be a theologian, thinking that perhaps he would say Syriac as well as Greek and Hebrew plus a good foundation in modern philosophy and psychology. Instead Holmer would say, ‘Well, I would think that a hunger and thirst for righteousness would be required. And meekness. It helps to be poor in heart.’” Michael Linton visited Holmer in Minnesota shortly before his death. He had Parkinson’s and his wife Phyllis was in frail health, but he could still read and was as alert as ever. “He talked with gratitude about his life, his children, and his colleagues. We shared some chocolate and prayed and said our goodbyes.” Paul Holmer, Requiescat in pace.

• It would seem to be a slam dunk for Barry Lynn of Americans United for Separation of Church and State. The fellow works so hard at dividing Americans over fake alarms about First Amendment violations, but this time he is on to something. Sun Myung Moon, under apparent U.S. Senate auspices, put a big costume shop crown on his head and another on his wife’s and read a declaration that “declared to all heaven and earth that Reverend Sun Myung Moon is none other than humanity’s Savior, Messiah, Returning Lord, and True Parent.” The declaration was read in Korean, so the senators and representatives present weren’t sure what was happening. Said Roscoe G. Bartlett, Republican of Maryland, “We have the king and queen of the prom, the king and queen of 4-H, the Mardi Gras and all sorts of other things. I had no idea what he was king of.” The politicos claimed they were lured to the meeting because their constituents were getting citizenship awards from one of Mr. Moon’s front organizations. Never mind, it’s the sort of thing that should not be happening in a Senate meeting room. Huffed Barry Lynn, “You had what effectively amounted to a religious coronation in a government building of a man who claims literally to be the savior.” I am grateful for the opportunity to agree with Mr. Lynn. We are also indebted to the New York Times for highlighting this outrage on its front page. As the Lord Mayor of Dublin, John Philpot Curran, said on July 10, 1790: “The condition upon which God hath given liberty to man is eternal vigilance.”(See also Elmer Davis, 1954.) Admittedly, coronations in the U.S. Senate office building are not a regular thing, since most senators would respectfully decline the demotion, but staunch friends of this constitutional republic will follow the advice of Madison in taking alarm at the first experiment with our liberties. A tip of our crown to Barry Lynn and Americans United.

• Despite our unflagging efforts, aided by outside proofreaders, typos still crop up from time to time. With new technologies of electronic transmission we cannot even blame the fabled “printer’s devils.” So it is with considerable relief that we received the following item forwarded by a reader who found it on the Internet: “I cdnuolt blveiee taht I cluod aulaclty uesdnatnrd waht I was rdanieg. The phaonmneal pweor of the hmuan mnid. Aoccdrnig to rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deson’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be in the rghit pclae. The rset can be a taotl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit a porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe. Amzanig.” Amazing indeed.

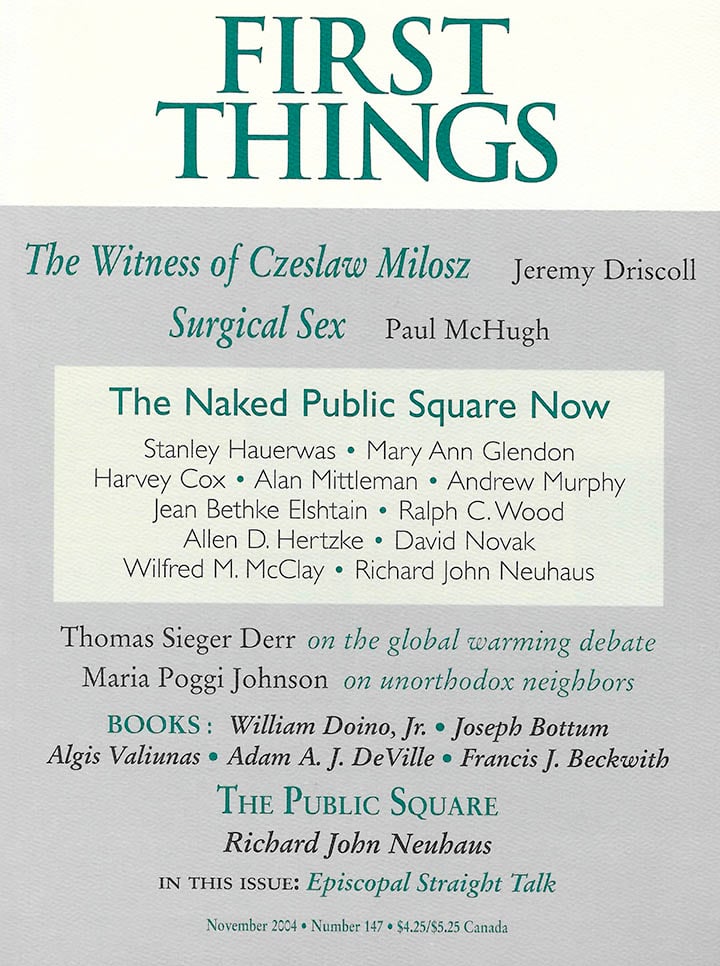

• New groups of ROFTERS (Readers of First Things) are cropping up at a most remarkable rate. In fact, there are so many that there is no longer space enough to list them all here. We will post newly formed groups and contact information for their conveners as promptly as possible, along with already established groups, on the website, old.firstthings.com. Please go there to see if there is a group near you. If you wish to convene a ROFTERS group, please contact Erik Ross at er@firstthings.com. These are independent groups. How often they meet and the format of discussions are questions left entirely to conveners and their ROFTER friends. Of course it is very gratifying to the editors that there is such interest in exploring with others the questions addressed in the journal. We thank you.

Sources:

Metrosexuals in glass elevators, Seattle Times, August 8, 2004. Lesbians in the library, National Post, August 21, 2004. Kimball review, Wall Street Journal, September 3, 2004. Placher on the Trinity, Context, September 2004. Advance directives, www.archinternmed.com, July 26, 2004. Greeley, Chicago Sun Times, June 11, 2004. Abortion nuns, Our Sunday Visitor, July 18, 2004. Prior to Zionism, Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation press release, July 26, 2004. Kirsch on Himmelfarb, New York Sun, September 1, 2004. Dulles on Dallas, America, June 21–28, 2004. JFK’s Catholicism, Commonweal, June 18, 2004. Moon’s coronation, New York Times, June 24, 2004.

Why I Stay at Notre Dame

I have been associated with the University of Notre Dame since 1984, first as a graduate student…

A Critique of the New Right Misses Its Target

American conservatism has produced a bewildering number of factions over the years, and especially over the last…

Europe’s Fate Is America’s Business

"In a second Trump term,” said former national security advisor John Bolton to the Washington Post almost…