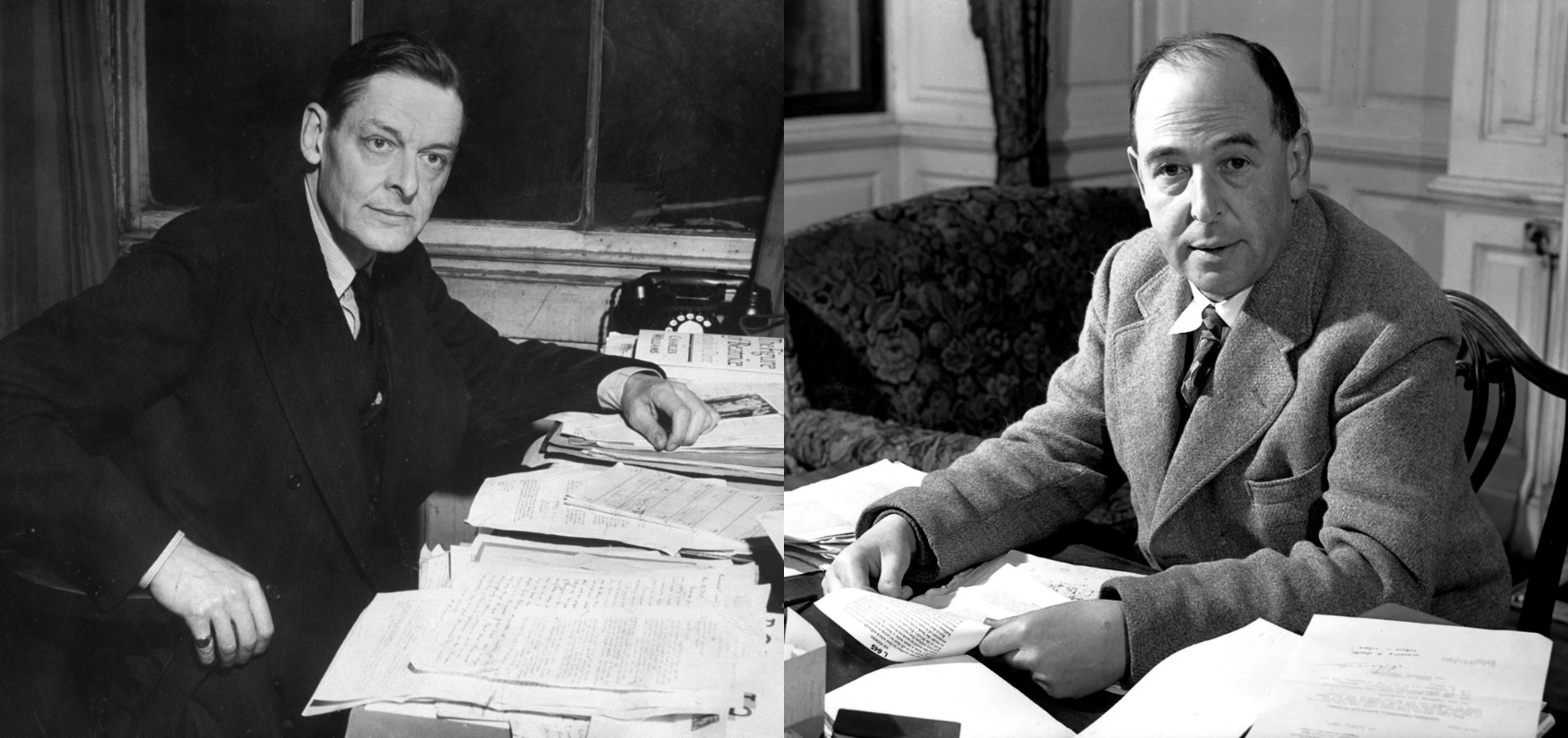

Melanie McDonagh’s Converts, reviewed in First Things last month, allows us to gaze close-up at the extraordinary procession of eminent literary, artistic, and intellectual figures that made its way over the threshold of the Roman Catholic Church from the 1890s right up until the 1960s. Wilde, Waugh, Greene, Anscombe, so many others: It is a mesmerizing spectacle. But there was, one might say, another contemporaneous procession. It was similar in some ways to the first, containing figures of equal stature and interest. However, this procession circled the Church, hugging its outer walls, but never entered. And at the head, I would place C. S. Lewis and T. S. Eliot.

Raised in Protestant Belfast, the young Lewis was something of a New Atheist avant la lettre; not for him was the “comfortable little universe with heaven above and hell beneath, an absolute up and down and a bare six thousand years of recorded history.” (One can imagine Richard Dawkins nodding and smiling.) He later made his way back to Christianity, guided, as Joseph Pearce has pointed out, by numerous Catholics: J. R. R. Tolkien and other papist friends, but also a string of authors whom Lewis greatly admired—G. K. Chesterton, Coventry Patmore, John Henry Newman. In Dante’s poetry, he found a beauty and complexity “very like Catholic theology—wheel within wheel, but wheels of glory, and the One radiated through the Many.”

Lewis’s preferred form of Anglicanism embraced several Romish ideas and practices. He went to confession regularly. He had a strong belief in purgatory and held that the Eucharist was more than symbolic. He opposed contraception and disagreed strongly with the notion of women priests. (“The Priest at the Altar must represent the Bridegroom, to whom we are all, in a sense, feminine,” he wrote to Dorothy Sayers.) On the wall of his bedroom in Oxford, Lewis hung a photograph of the Shroud of Turin.

Lewis benefited from Catholic action as well as ideas: Sisters of the Medical Missionaries of Mary in Ireland frequently treated his dear brother Warnie for alcoholism, continuously returning the latter to health but also upending his Belfast-grown preconceptions. Expecting to find himself somewhere “a little repulsive, almost ogreish” in keeping with “the R. C. religion,” he was instead surrounded by “a life of joy” in “a place of laughter” and struck by “the radiant happiness of these holy and very loveable women.”

C. S. Lewis was a man set fair for Rome then, one might have thought. (Several reviewers of his allegory The Pilgrim’s Regress assumed that he actually was Catholic.) Lewis scholars such as Fr. Michael Ward (a convert), speaking last year in Oxford, and Joseph Pearce (also a convert), in his 2013 book C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church, seem to agree on the major doctrinal sticking points that prevented the author of Mere Christianity from (as Fr. Ward puts it) “following his own lead”: Mariology and, above all, papal infallibility. Moreover, Lewis believed that a great deal of his utility to Christianity had depended on “having kept out of all the dogfights” between denominations.

There is little doubt his conversion to Catholicism would have stirred things up enormously (and might indeed have diminished his “utility,” as he perceived it). However, Pearce, who vigorously pursues various contradictions in Lewis’s stance, also identifies a deeper, psychological barrier: As a son of loyalist Protestant Ulster, Lewis could not ultimately find a way past deep, ancestral instincts and prejudices. Escaping the past isn’t easy in Ireland.

T. S. Eliot converted to Anglicanism in 1927, four years ahead of C. S. Lewis. Lewis, as it happens, strongly disliked Eliot’s poetry and felt equal antipathy toward his form of religion, which he saw as “trying to make of Christianity itself one more high-brow, Chelsea, bourgeois-baiting fad.” (The two actually became good friends later in life.)

Eliot developed a three-part worldview: “classicist in literature, royalist in politics and anglo-catholic in religion.” Curiously, growing up in a New England Unitarian household, he had had a Catholic Irish nanny to whom he was devoted. She would take him occasionally to the Church of the Immaculate Conception in St. Louis (which he “liked very much”) and explained to a six-year-old Eliot theological arguments for God as first cause. Eliot was eventually to conclude that Unitarianism was “a bad preparation for brass tacks like birth, copulation, death, hell, heaven and insanity.”

Like Lewis, Eliot appeared to have lines ready for when he was challenged about “not following his own lead” from Anglo to Roman. When Catholic journalist and publisher Tom Burns observed that he wished Eliot wasn’t a heretic, the latter replied, unperturbed: “I’m not, I’m a schismatic.” While he did not shy away from Mariology, even in his poetry (see, for example, his appeal to “Figlia del tuo Figlio, / Queen of Heaven” in “The Dry Salvages”), it does appear that, like Lewis, papal infallibility was one Roman doctrine he could never swallow. And he too was loyally keeping to the ways of his forebears, this time in England.

Who else might we place in the procession? Another great poet of the twentieth-century, W. H. Auden, re-embraced the Anglo-Catholic Christianity of his childhood, while his brother John made it all the way back to Rome. The Anglican Patrick Leigh Fermor—soldier, adventurer, bon viveur, raconteur, memoirist, and one of the century’s greatest prose stylists—was in the habit of putting “R. C.” on official documents up to the end of Second World War (when he was thirty years old). He also claimed to be descended from Irish Catholic nobility who fought at the Siege of Vienna of 1683 as counts of the Holy Roman Empire.

Readers may have their own suggestions. And perhaps one day these giants too will have a book to memorialize their near conversions.

The Testament of Ann Lee Shakes with Conviction

The Shaker name looms large in America’s material history. The Metropolitan Museum of Art hosts an entire…

Why I Stay at Notre Dame

I have been associated with the University of Notre Dame since 1984, first as a graduate student…

What Virgil Teaches America (ft. Spencer Klavan)

In this episode, Spencer A. Klavan joins R. R. Reno on The Editor’s Desk to talk about…