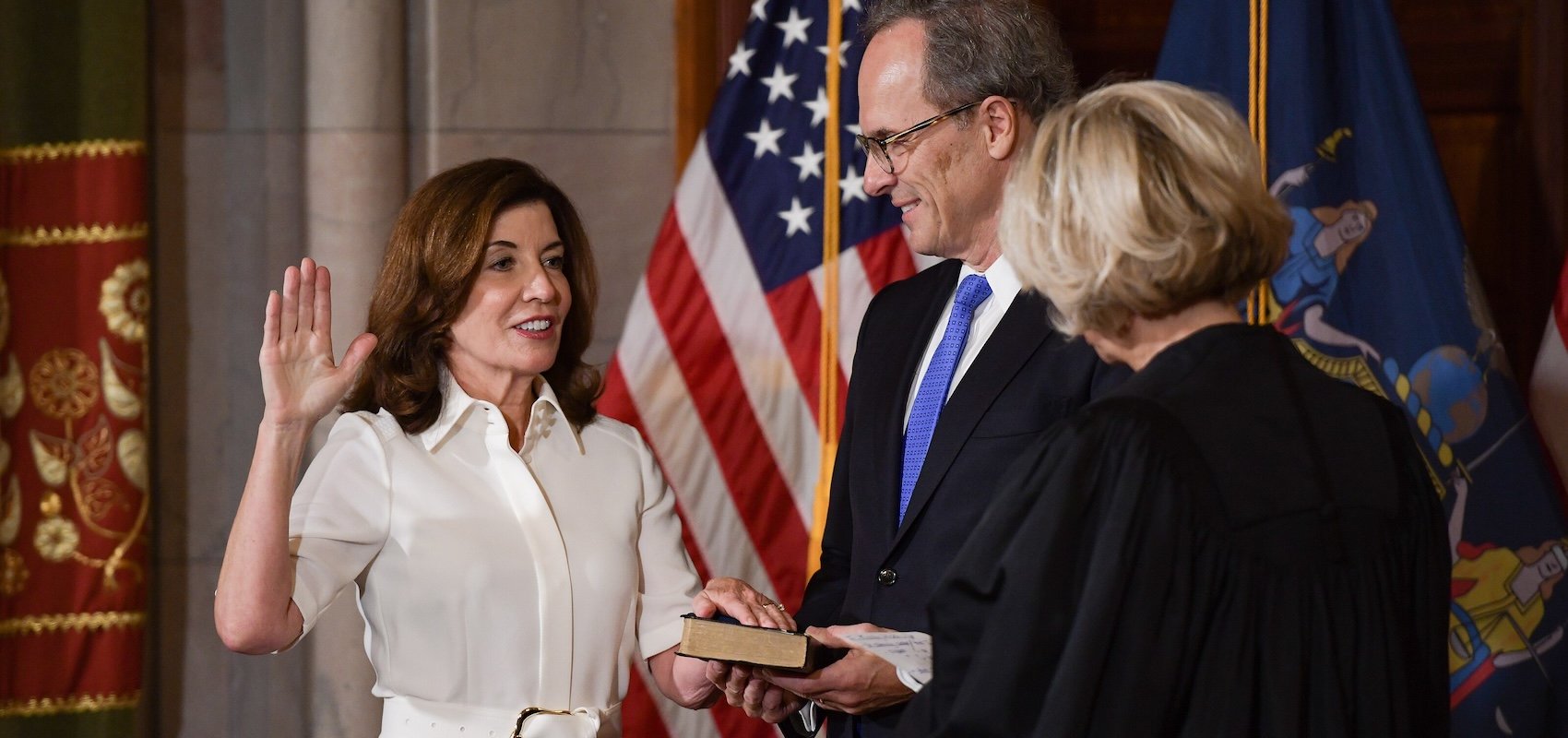

Yesterday, New York Governor Kathy Hochul announced her intention to sign the Medical Aid in Dying Act, a bill that will legalize physician-assisted suicide in the state. Explaining how she came to this “difficult decision,” Gov. Hochul writes:

I reflected on this during a Catholic funeral Mass for a family friend where the priest spoke of the welcome home to eternal life. I was taught that God is merciful and compassionate, and so must we be. This includes permitting a merciful option to those facing the unimaginable and searching for comfort in their final months in this life.

Lost on the governor is the irony that for almost all of Church history, those who took their own life were denied a Catholic funeral and burial, so grave a public scandal was suicide deemed. While current norms reflect an understanding that such persons may not be responsible for their actions, due to physical or psychological distress, those entrusted with their care ought to be.

None of that denies the genuine pain that terminally ill patients and their loved ones often experience. The problem of suffering is precisely that—a mystery that challenges even persons of deep faith. For Christians, the mystery is revealed, if not solved, in the Cross on which God himself took on the depths of human suffering and pain. In the long shadow of Calvary, suffering becomes not a problem to be solved but an invitation, admittedly not always welcome, to share in that same redemptive work. Thus can St. Paul exhort believers to “complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions” (Col. 1:24).

The merits of the Passion are infinite; what is lacking is our own participation, becoming channels through which that treasury of grace can flow to every person. That process stretches the soul, expanding it outward beyond oneself. Such magnanimity extends to those who care for the sick and suffering, often calling forth heroic self-sacrifice and eliciting deeper wells of love. And God remains neither silent nor indifferent to such pain. He who can no longer suffer, but whose glorified body yet bears the wounds, suffers along with them. The word compassion, evoked by Gov. Hochul in her apologia, literally means co-suffering: accompanying those in pain, carrying that cross with them, and loving them to the end.

That message did not come across to Gov. Hochul in the Mass she attended, perhaps in itself an indictment of modern-day Catholic funerals that are heavy on saccharine sentimentality and light on the sobering reality of death and judgment. Instead, the governor invokes the principles of “choice and freedom,” as she “proudly” connects this legislation to her championing of abortion rights and same-sex marriage. Indeed, there is a through line: Why can a human person considered burdensome or unwanted be legally killed only at the first stages of life but not the last? And the nominalism that attempts to redefine marriage through linguistic gymnastics (“marriage equality”) here employs the same Orwellian tactics, calling the deliberate killing of an innocent person “medical aid” that is not “about shortening life but rather about shortening dying.”

The governor, though, lacks the courage of her own agonized convictions. If this decision is really about “bodily autonomy” and “an individual’s deeply personal decisions,” why limit the right to die only to those who are terminally ill? Why should it otherwise remain a felony in New York State to assist someone in taking his own life? Such is the slippery slope that inevitably follows upon this precedent. Wherever assisted-suicide has become legal, the restrictions have quickly loosened. As seen so many times with abortion, the definition soon expands to cover not just physical health, but mental and emotional health as well.

For all the guardrails that Hochul touts (for example, a physician must be certain that a patient has less than six months to live, an assessment that presumes divine omniscience), such an expansion becomes inevitable when the “dignity and sanctity of life” are no longer inherent qualities, but now placed on a sliding scale of subjective criteria. Once we admit that life may indeed not be worth living, such guardrails quickly fade into irrelevance. What pressures, even self-imposed, will the dying now face so as not to burden their own loved ones, emotionally and financially? What abuses and errors in judgment will result in an outcome that can be regretted but never reversed? The governor wishes only to allow people to “speed up the inevitable.” But death remains inevitable for every one of us, and its timeline is not ours to determine.

Gov. Hochul concludes her contorted rationale by invoking gauzy language of spending one’s final days “with sunlight streaming through their bedroom window” and hearing “the laughter of their grandkids echoing in the next room.” That is, until the plug is pulled. No, there is no sunlight or laughter in this bill, but only darkness and sorrow. The governor now heads into a re-election campaign having burnished her credentials as a champion of the culture of death, leaving those most vulnerable, at life’s beginning and end, without the legal protections that their God-given dignity demands. Regardless of the outcome in November, Gov. Hochul has made New York a colder, crueler, and more callous state.

How Hipsters Gave Us Trump

Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign was powered by its embrace of the white working class. It also…

While We’re At It

January 8 marked the seventeenth anniversary of Fr. Richard John Neuhaus’s death. We owe the existence of…

The Case for Christian Nationalism

Recent polling paints a disturbing picture: Fewer than half of Gen-Z Americans are extremely or very proud…