America’s abortion regime and the absolutist ideology that animates it is part of a war by the powerful on the weak. This is true not only because it targets unborn children in the womb, the most helpless members of our society. It is also true because the regime is sustained by the rich while it targets the poor. American elites are the country’s main constituency for abortion absolutism while its consequences are visited upon the working class and the underclass. Ending America’s war on the weak is not only a legal project. It is a political, economic, and cultural project for the next pro-life generation.

Since the Supreme Court handed down Roe v. Wade in 1973, the United States has maintained one of the most extreme abortion regimes in the world, claiming more than 60 million lives. Seven U.S. states plus the District of Columbia even fund abortion on demand without gestational limits of any kind. These legal structures are supported by an absolutist sentiment that is on the rise. Since the national polling firm Gallup began asking Americans their views on abortion in 1975, never have more than 34 percent of respondents supported a regime of “legal under any circumstances.” Gallup’s 2021 poll put that figure at 32 percent, the highest tally since the first Clinton administration. Since 2001, Gallup has also asked Americans whether abortion was, regardless of legality, morally right or wrong. In 2021, a record-high 47 percent stated that abortion was in their personal view “morally acceptable.”

This ideology appeals primarily to American elites. Whereas only 21 percent of those with a high school diploma or less favor a regime of “legal under any circumstances,” 43 percent of college graduates currently do. Only 33 percent of Americans with a high school diploma or less believe abortion to be “morally acceptable,” compared to 72 percent of those with an advanced degree. We see the same story with household income: 38 percent of the poorest (those making less than $40,000 a year) consider abortion “morally acceptable,” while 63 percent of the richest (those making more than $100,000) say as much. Sixty-two percent of Americans with a high school diploma or less consider themselves “pro-life”; only 32 percent of college graduates do.

America’s social classes do not practice what they profess, however. Though the wealthy and the highly educated support and agitate for open access to abortion, poor and working-class women are the most likely to actually procure one. Women whose highest level of education is a high school diploma have twice the abortion rate of women with a college degree, and the abortion rate among women in poverty is a grim six times that of women with family incomes above 200 percent of the federal poverty line. The most enthusiastic advocates of abortion-on-demand are American elites. The highest rates of abortion in the United States are among poor women, cohabiting women, black women, and women in their twenties.

Yet in the public debate over abortion, elites assign themselves the starring roles in the national drama. Take 2021 media sensation Paxton Smith, the valedictorian speaker at Lake Highlands High School in suburban Dallas, who drew national attention for her three-minute speech against Texas’s new fetal heartbeat abortion law. In her speech, Smith placed herself at the center of the debate, describing the law as a “war on my body” (which will also be the title of her book, to be released next year). This description obscured not only the obvious war on her own future child, but also the fact that a white, single, (upper-) middle-class teenager is about the least likely woman in America to have an abortion.

Nearly ten years ago the progressive magazine The American Prospect asked, “Why does the ’70s-era image of the white, middle-class teenager as the typical abortion patient persist?” The answer, of course, is that the country’s most dogmatic and radical abortion supporters are elite women who understand themselves to be the primary beneficiaries of Roe. The college-bound white, middle-class teenager imperiled by pregnancy is culturally stereotypical precisely because she is a self-projection of our elites.

Paxton Smith ably deployed this class trope. “I have dreams and hopes and ambitions,” she said. “Every girl graduating today does, and we have spent our entire lives working towards our future. . . . I am terrified that if my contraceptives fail, I am terrified that if I am raped, then my hopes and aspirations and dreams and efforts for my future will no longer matter.” This class lament drew the enthusiastic public support of prominent feminists such as Hillary Clinton, Rep. Carolyn Maloney, former Texas gubernatorial candidate Wendy Davis, and superlawyer Gloria Allred. The message is as frank as it is depraved: The death of unborn children is a necessary condition of female equality and success.

The class ideology that abortion is necessary for women’s empowerment bears a distasteful resemblance to pro-slavery arguments used in the run-up to the American Civil War. Thirty years ago, the liberal abortion mantra was “safe, legal, and rare,” a position not unlike that of late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century American slave-owners, who viewed the “peculiar institution” as an evil, if perhaps a necessary one. Yet much like the evolution of contemporary feminism toward “shout your abortion,” Southern intellectuals in the 1830s changed course to insist that slavery was not evil at all but rather a positive good. South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun became the most prominent among the voices advancing such arguments. In Calhoun’s view, slavery was good because it reconciled capital and labor, thus freeing the South from the “disorders and dangers” of class conflict. At the same time, slavery freed whites from servile labor “unsuited to the spirit of a freeman.” The message was as frank as it was depraved: (Black) slavery is a necessary condition of (white) social equality and free institutions.

America is no stranger to claims that the foundation of equality is a radical and deadly inequality. Against this view, the pro-life movement asserts the moral equality of every human being. Its concern for human life does not end at birth. The contributions of pro-life organizations to crisis pregnancy centers, maternal health care, parenting classes, adoption, foster care, and post-abortion ministry are well known to all who want to know. Yet this traditional pro-life work depends for its success on a social and cultural infrastructure that is disintegrating.

We know that marriage is society’s best wealth-generating and commitment-building institution. Yet marriage no longer defines the lives of working-class (or, increasingly, middle-class) Americans. Its demise is a mortal threat to the successes of the pro-life movement. Despite recent declines, America’s abortion rate is still higher than that of most Western and Central European countries. It is also more than 50 percent above the rates of countries such as Italy, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Lithuania, which have liberal abortion regimes but also maintain a robust culture of marriage. Poor women and cohabiting women have the highest rates of abortion in the United States. Ending abortion will require rebuilding marriage.

How can this be done? By normalizing a single model of the family most conducive to the successful bearing and raising of children in every social class. In my 2018 book From Tolerance to Equality, I present evidence for the existence of three family models lived out in the contemporary United States. I label these models “blue,” “red,” and “Creole.” The blue family is a socially liberal model, favored by contemporary policy advocates and practiced primarily by elites. In the blue model, sexual behavior is governed by norms of individual autonomy balanced by individual responsibility. Marriage is ordered toward companionship rather than childbearing. Fertility is low, which is largely the outcome of late marriage, strong and consistent contraception use, and a fallback to abortion, all organized around long periods of education capped by successful professional or managerial employment that defines the class.

Though it delivers material benefits for elites, the blue family is poorly suited as a universal model. This is especially true for America’s working class, which increasingly practices a “Creole” model. This family type is characterized by matriarchy, father absenteeism, weak parental control over children, unstable sexual unions dominated by men, nonmarital births, and high fertility. Though many of these practices are negative, the Creole family positively places a high value on children and the mother-child bond. Marriage rates are low, but marriage itself retains high social prestige. Without secure professional-managerial-class employment waiting at the end of a long period of education and sexual responsibility, the blue model’s attractiveness to the working class is understandably low.

Instead, the wide promotion of the “red” model is a common way forward. The red family is a socially conservative ideal prescribing a unity of sex, marriage, and procreation. Unlike the Creole family, the red model delegitimizes cohabitation while successfully incorporating men into the family as husbands and active fathers. Unlike the blue family, the red model recommends early marriage and childbearing, and it places children at the center of the parental bond. By culturally proscribing cohabitation and prescribing children, the red family is the strongest pro-life ideal.

There is much that public policy can do to promote the red model. The federal government should make permanent universal monthly child benefits resembling the temporary allowances instituted this year and structured so as to encourage marriage. It should also pursue industrial policy targeting the expansion of skilled working-class employment. State governments should expand non-college educational tracks to impart greater labor market skills to working-class men and make them more attractive husbands. They should also implement Canadian-style legal regimes that effectively treat cohabiting couples as married after two years.

Promoting a culture of life in the United States does not end with overturning Roe. Ending the war on the weak needs to be followed by a period of reconstruction. It is time to begin thinking about the laws and policies that will render abortion unthinkable.

Darel E. Paul is professor of political science at Williams College.

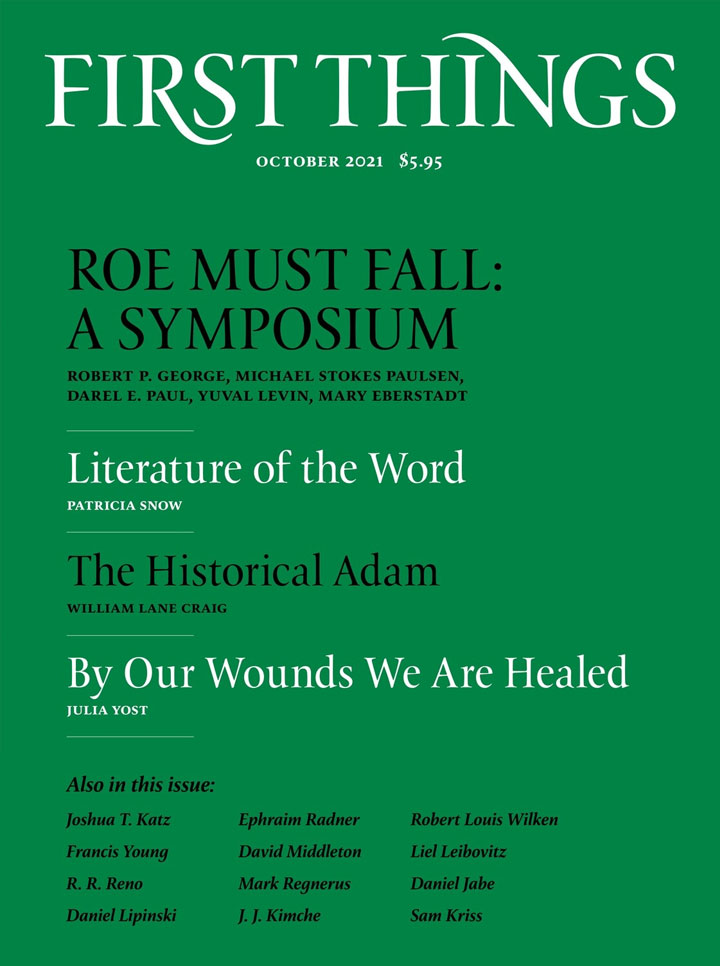

Image by Martin Junias via Creative Commons. Image cropped.