The Mirror and the Light

by hilary mantel

henry holt, 784 pages, $30

The arrival of this final installment of the Thomas Cromwell trilogy, penned by “one of our most important living writers,” has precipitated an avalanche of adulation for its author and her great work, already decorated with two Booker Prizes and no doubt in the running for a third. The Mirror and the Light concludes a project that began a decade ago with Wolf Hall and continued in 2012 with Bring Up the Bodies. The attention these three books have commanded now compels a summative assessment of the project, which occupies disputed ground between history and fiction. Of course, it is ultimately fiction (it has won the Booker Prize, not the Wolfson). But it is not classic historical fiction. Classically, historical fiction sets invented characters in an imaginary story situated in a realistic context. The ingenious and deservedly popular detective stories of C. J. Sansom are a case in point. Verisimilitude is lent by the judicious use of historical detail and by fictitious interactions with genuine historical figures. The Cromwell trilogy, by contrast, is better understood as fictionalized history. It takes as its theme the rise and fall of Thomas Cromwell (ca. 1485–1540), beginning with his service in the household of Cardinal Wolsey and ending sharply on the block. All but a handful of minor characters are historical figures, and historical events form the spine of the narrative.

There is no denying Wolf Hall’s commercial and social success. Prizes galore, spin-off dramas and adaptations on stage and TV, dizzying sales figures that revitalized the novelist’s lengthy backlist, myriad reviews and interviews and features (mostly favorable), all crowned by a distinction unique for a living author—the installation of her portrait in the British Library (at the top of the stairs leading up to the Manuscripts Reading Room). Yet the success of Wolf Hall itself, back in 2009, owed more to its historical than to its literary qualities or pretensions. Its appearance was timely, coinciding with the quincentenary of Henry VIII’s accession to the English throne, and the early publicity insisted upon the depth and detail of the historical research that had gone into its creation. A typical early review saw Wolf Hall as marking “a significant shift in the way . . . readers interested in English history will henceforth think about Thomas Cromwell.” The author herself emphasized the novelist’s responsibility to “adhere to the facts as closely as possible,” to “work with intractable facts and find the dramatic shape inside them,” and would later revel in the observation that she had “made a fetish of historical accuracy.” On the literary side, however, even some of the warmest admirers of the book had problems with its use of the third-person historical present to communicate an essentially stream-of-consciousness narrative: for the entire action is witnessed through the eyes, including the inner eye, of the protagonist. Its unique selling point, the point that caught the eye of most reviewers, was its radical reappraisal of two historical figures. The first was Thomas Cromwell, who was transformed from the obscure and sinister hatchet-man of Henry VIII into a sympathetic blend of social idealism and political realism. The second was Thomas More, who was transformed from Robert Bolt’s tragic martyr for freedom of conscience into a hate-filled prophet of religious fanaticism.

Considered as an artistic project, the most salient feature of the trilogy is its radical instability, an instability that runs through its central character. The most revealing thing the author has told us about the genesis of Wolf Hall is that she originally conceived it as a single novel, which would take Cromwell’s story to its end in a single sweep. What then happened was that as she got to grips with the pivotal events of 1534–35—in which Thomas More was targeted and ultimately destroyed by Henry VIII’s regime for his refusal to go along with the king’s assumption of the title of Supreme Head of the Church of England—she found the duel between More and Cromwell irresistibly dramatic. It became the dominant theme of the narrative, with a natural end in More’s execution. The single novel was therefore recast as a trilogy, with each novel closed by a beheading: Thomas More’s in 1535, Anne Boleyn’s in 1536, and Cromwell’s in 1540. But what one should note is that Thomas More in effect hijacked the story, despite his allotted role as a secondary presence. As Cromwell himself says much later, in a rather different context, “It all goes back to More.” The reason for this is that while it is entirely possible to talk about Thomas More without talking about Thomas Cromwell, it seems next to impossible to talk about Cromwell without talking about More. More’s very impact on the story uncovers one of the structural weaknesses in the project: The central character is not strong enough to carry the load placed upon him. It was the portrayal of More, not of Cromwell, that accounted for Wolf Hall’s early vogue. More’s impact on the project is the key to its failure not only on the historical but also on the literary level. One early reviewer, noting that “There is historical truth, and there is imaginative truth,” purred that Wolf Hall respected both. This is a judgment that is difficult to endorse.

The author certainly knew what she was about. In 2015 she complained that “some people have seen the novel as an outrageous attack on the reputation of Thomas More and as a travesty of the facts,” to which she responded, “But the truth is I have not discovered anything new about More.” Now it is indeed true that she has “not discovered anything new about More.” Some of what is said to his discredit is familiar from the charges of his Tudor enemies and detractors. The author claims to have depicted him “from the point of view of the London evangelical community,” but the point of view more often is that of the typical New York Times columnist. Much is derived from a few recent historians and writers, and the rest is the product of the author’s imagination.

The Thomas More of Wolf Hall is first introduced to us by Thomas Cromwell as “some sort of failed priest, a frustrated preacher,” and this is a fair harbinger of the catena of long-range psychoanalysis, secondhand “scholarship,” and old-fashioned character assassination that follows. This purported insight was first put about by a modern biographer, Richard Marius, on the flimsy basis of Erasmus’s report that More had in his youth considered a vocation to the priesthood, only to reject the idea because he had no vocation to celibacy. Linking this to More’s alleged obsession with sex in his voluminous religious polemics, Marius constructed a warped psyche tormented by sexual temptation and frustration. This construct was enthusiastically taken up by the historian Geoffrey Elton, whose own improbable idolization of Cromwell as the architect of modern England impelled him to belittle any rivals among Cromwell’s contemporaries. More’s so-called obsession with sex comes down to his harping on the fact that Luther broke his own vow of celibacy by marrying a former nun—a tactic More deploys consciously, with the deliberate aim of discrediting Luther. If this amounts to evidence of a tormented psyche, what is to be made of the fact that there is more talk of sex in the Wolf Hall trilogy than in More’s complete works?

The character of Cromwell himself is the sort of fantasy figure who fills popular fiction. As irresistible to women as James Bond (though more restrained in his exercise of that power), as politically farsighted and idealistic as Josiah Bartlet, as observant as Sherlock Holmes, even as good an archer as Robin Hood, he is in general as astonished at himself as is his creator. There really are no limits to his capacities. He will offer a penetrating analysis of the verse of Thomas Wyatt in terms worthy of an Ivy League professor or an ingenious improvement on the mechanical advantage in a treadmill. When he sees a comet in 1531, his instinct for astronomy associates it infallibly with one seen back in 1456. (Edmond Halley finally caught up with him on this in the 1680s: The author herself has warned about the pitfalls of hindsight.) In Bring Up the Bodies, Cromwell brings Henry back from the dead by means of a timely anticipation of CPR. This is hardly sophisticated characterization, and one wonders whether identification or infatuation is uppermost in the author’s mind.

There is at least plenty of Cromwell, though he remains a puppet, jerked about to display this or that prejudice of his creator. The rest of the characters are disappointingly one-dimensional, and there is a comfortingly old-fashioned division between the goodies (almost all the Protestants, with the exception of Anne Boleyn) and the baddies (almost all the Catholics, with the half-exception of Catherine of Aragon). One might as well be reading Charles Kingsley. By the time one is halfway through The Mirror and the Light, moreover, one is wondering whether there is a genuinely sympathetic female character in the entire opus. (To be fair, there are one or two, in modest walk-on parts as wives or lovers.) The author may betray pity for Catherine of Aragon, but certainly not liking. As for the queen’s daughter, Mary Tudor, she staggers through the novel like one accursed: plain, ugly, stubborn, deceitful, timorous, sickly, stupid, bigoted, clumsy, ill-dressed, unloved and unlovable. . . . Rarely, one feels, has any human creature been so ill-favored.

In Wolf Hall, Cromwell rather curiously presents More as a misogynist who hates and is hated by women, which sits oddly with his decision to emulate More by giving his daughter a fashionable humanist education. In terms of characterization, though sadly not in plot, the Wolf Hall trilogy is pure melodrama. Stephen Gardiner: “a crouching brute nibbling his claws, waiting for his moment to strike.” Eustache Chapuys: his face, “smiling, a mask of malice.” This last phrase, by the way, is one with which the author was obviously rather taken. Thomas More also wore the “mask of malice.” One had hoped to see the phrase a third time, but it was not to be.

The overflowing character of Cromwell, however, continually loses shape because of the conflicting imperatives to establish him as the moral superior of More yet also as the near infallible consigliere of a brutal yet curiously babyish monarch. You can be one or the other, but not really both. “More says it does not matter if you lie to heretics, or trick them into a confession,” the morally superior Cromwell preaches censoriously in Wolf Hall. This moralism comes strangely from the Cromwell who, in Bring Up the Bodies, tricks Mark Smeaton into furnishing the confessions he needs to destroy Anne Boleyn. Again, when Cromwell considers threatening Thomas More with a lingering death—because, of course, More is a weakling and a coward who cannot even take Cromwell’s manly handshake without flinching—he concludes that he will not sink so low: “He knows he will not do it: the notion is contaminating.” Not, though, by 1537, when he lectures Thomas Wriothesley on the dark arts of political interrogation.

Cromwell, though, is quite a decent chap, really. He certainly tells us so often enough, and in case we are reluctant to take his unsupported word for it, we have confirmation from none other than Thomas More’s son-in-law, William Roper, who ruefully assures Cromwell, “We know you are not vengeful, sir. Though, God knows,[More] has never been a friend to your friends.” However, this does not sit especially comfortably with one of the few threads of authorial invention that run through the trilogy, namely the conceit that Cromwell was motivated to seek high office in his own right in order to inflict condign punishment on those who had brought down his erstwhile and beloved master, Cardinal Wolsey. This temporary character trait is called in to explain Cromwell’s persecution of the alleged lovers of Anne Boleyn. While Mark Smeaton strummed the lute, it transpires, George Boleyn, Mark Brereton, Henry Norris, and Francis Weston had been the disguised dramatis personae of a court pageant in which the figure of the late cardinal was consigned gleefully to hell (a sort of masque of malice). Thomas “you are not vengeful, sir” Cromwell had, it seems, nursed this vicarious grievance until fate and a disenchanted monarch presented him with revenge on a plate.

The trilogy as a whole is the product of prodigious research. The Mirror and the Light, pursuing its painfully slow and at times rudderless course, can read to the professional Tudor historian like a summary of that vademecum of researchers, the Letters and Papers . . . of the Reign of Henry VIII. Yet historically, too, the project falls short alike of the pretensions of its author and the praises of its admirers. One example: We are shown an enlightened Cromwell despising More for employing torture. During one of their exchanges in the Tower, Cromwell rebukes him with it to his face, and More can find nothing to say. In the historical record, it is true, people accused More of using torture. Yet in the historical record, too, More refuted their accusations. You may prefer to conclude that he was lying. But you are not entitled to imply, as Wolf Hall does, that he could make no answer to the charge. In the historical record, moreover, we have evidence in Cromwell’s own hand authorizing the use of torture without any attempt to deny it or disguise it. It doesn’t matter how much of a fetish you make of accuracy over clothes or buildings or the weather if you can’t tell the difference between a man who used torture without a second thought and a man who, if he did use it, was at the very least embarrassed enough to lie about it. (The balance of the evidence on the question, by the way, can be summarized thus: The case against More consists of hearsay, while the case for the defense is his own direct testimony, published at the time and left unrefuted by his contemporaries.)

In Wolf Hall, Thomas More is central to the action. Through the remaining two volumes he continues to haunt Cromwell, who gradually reveals his counterpart’s most heinous crime, namely that More was the hidden paw behind the arrest in Antwerp of William Tyndale in May 1535 (by which time More had been in the Tower of London for more than a year). Hinting obliquely at it in Wolf Hall (“More has a sticky web in Europe still, a web made of money . . .”), the author doubles down on the claim in Bring Up the Bodies, and then in The Mirror and the Light depicts Cromwell delivering what amounts to a three-page summary of the source of the idea—a 2003 biography of Tyndale by the late Brian Moynahan. This is not the place to pick apart Moynahan’s bizarre thesis. Suffice it to say that there is not an iota of evidence for it in the historical record. The idea that in early 1535, when all his assets had been confiscated, and when his wife was writing to the king begging for assistance and relief, Thomas More was somehow financing and masterminding, from captivity in the Tower, an international plot to capture a renegade Englishman on the other side of the Channel . . . simply to say it out loud is to hear its absurdity. The author has often described her method in this trilogy as using imagination to “fill in the gaps between the facts.” This is not filling in the gaps between the facts: It is fantasizing an alternative reality around them—or some of them.

The haunting presence of More through the trilogy, however, unwittingly testifies to the very truth that the project seeks to obscure or overturn: Thomas More has never been forgotten; Thomas Cromwell has only recently been remembered. Nowhere is there a collection of Cromwell memorabilia to match the Moreana preserved at Stonyhurst College in Lancashire. People fell over themselves to write More’s biography, even in the Tudor era. The biographies by William Roper, Nicholas Harpsfield, and Thomas Stapleton all survive. The one by William Rastell is preserved only in a few stray fragments. Not a century has gone by without its share of biographies of More. Nobody bothered about Cromwell until the late nineteenth century, when the opening of the archive and the birth of professional history revealed his crucial role in the events of the 1530s. There have been more editions of Roper’s life of More than there have been biographies of Thomas Cromwell.

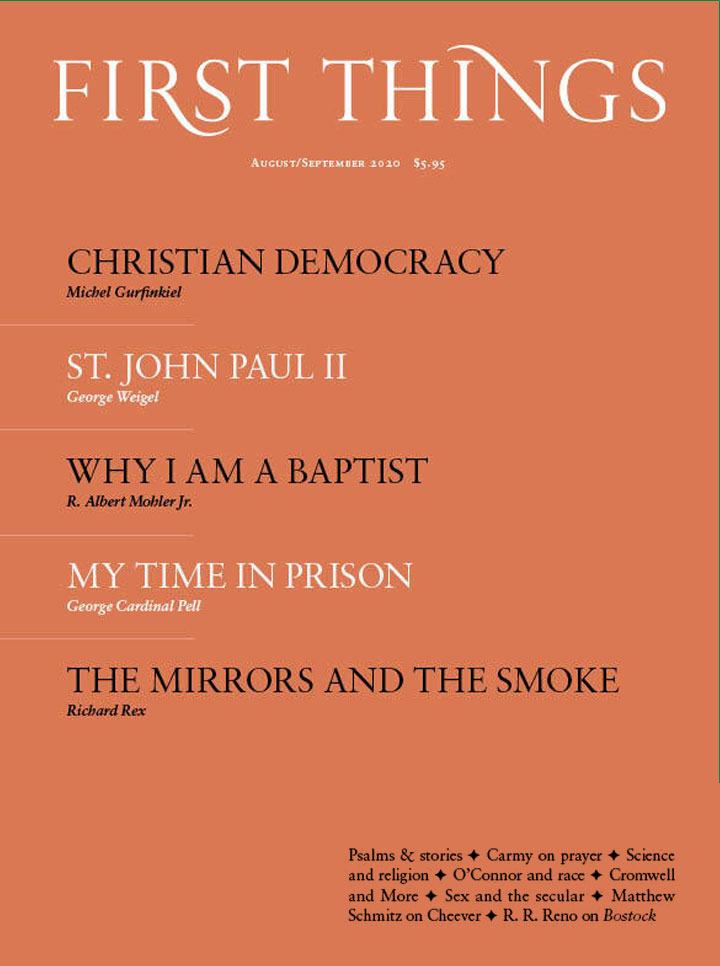

There is a reason for all this. One can see it at the Frick Collection in New York, where More and Cromwell gaze at each other across a fireplace, captured by the hand of the sixteenth century’s greatest portraitist, Holbein. The art critic Waldemar Januszczak once labelled Cromwell “the least attractive sitter in the whole of Holbein’s art.” Holbein’s More, in contrast, is famously and sublimely alive. Even the author of Wolf Hall has had to admit that Holbein’s Cromwell is an “incredibly dead picture.” This is a serious problem for her project, a problem at which Bring Up the Bodies glances sidelong, when Cromwell wryly muses on the risk of Holbein’s “committing another portrait” against him. The Mirror and the Light tries to meet it head-on. The artist is shown at work on his iconic Henry VIII, and we are laboriously assured by Cromwell that Holbein’s portraits only ever show the clothes rather than the man. Good effort. But seeing is still believing. If you did not know who Cromwell was, you would never give his picture a second thought. If you had never heard of More when you first saw Holbein’s portrait, you would have to ask who he was. And that is why, all in good time, the Wolf Hall moment will pass.

Richard Rex is professor of Reformation history at the University of Cambridge.