That All Shall Be Saved:

Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation

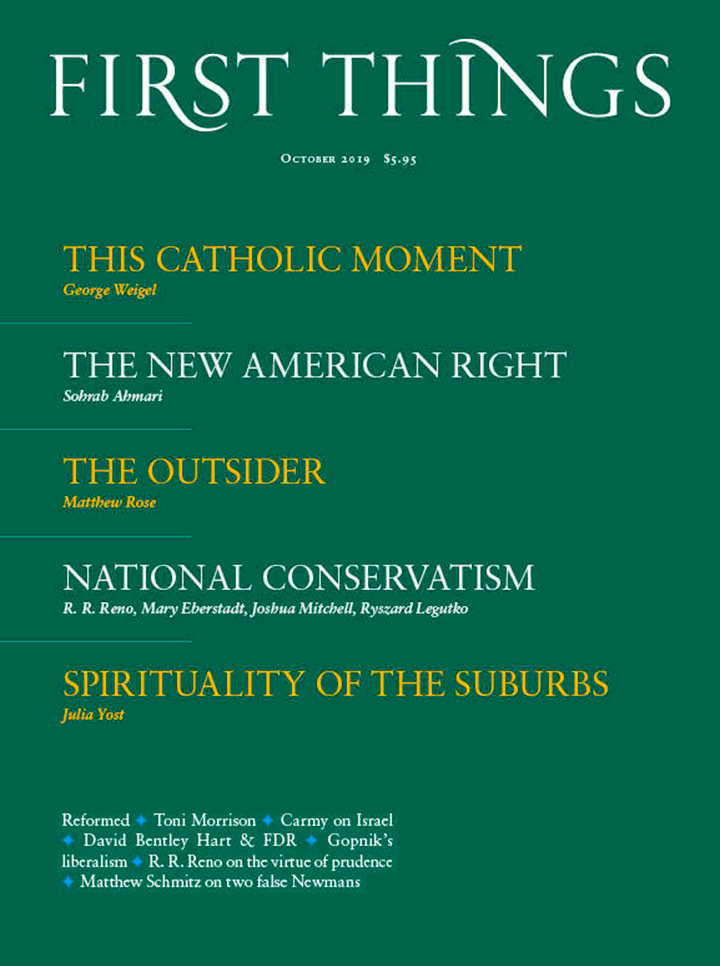

by david bentley hart

yale, 232 pages, $26

David Bentley Hart, familiar to readers of these pages as an intellectual pugilist who floats like a butterfly and stings like a bee, has entered the ring for the Big Fight. Armed with his recent translation of the New Testament, he is ready to prove that no one suffers eternal damnation. Almost the entire Western tradition, backed by much of the East, is in the other corner. In his corner are fellow followers of Origen, the evangelical universalists, and a motley crew of sparring partners from the gyms where he has trained. As he approaches the ring, he strikes a Luther-like pose. Of course he wants nothing whatever to do with Luther, or any other product of the Augustinian stable. But he will stand where he must stand; he can do no other. The Church has backed the wrong man. She is about to be taught a lesson.

The man in question is Augustine, the bête noire of universalists everywhere. He wears the black trunks. Hart is in the white trunks, standing in for Gregory of Nyssa, the man the Church ought to have backed and didn’t.

Full disclosure: Your fight-night reporter lacks what Hart regards as “a properly functioning moral intelligence,” that having been drummed out of him by long exposure to “profound misreadings of the language of Christian scripture, abetted by absolutely abysmal historical forgetfulness.” To make matters worse, he happens to be the sort of “self-deceiver” that, “say, a Catholic philosopher at a fine university, a devoted husband and father of five children” is likely to become, if in pursuit of the “soberly orthodox . . . he believes that he believes the dominant doctrine of hell.” Your correspondent can check most of these boxes. (His wife wonders about “devoted.”)

After some bobbing and weaving, Hart lands his first blows. Can we really love a god, Hart asks, “who has elected to create a reality in which everlasting torture is a possible final destiny for any of his creatures”? Could such a god be Christianity’s “infinitely good God of love”? That is the existential question. With it goes a more philosophical question. Is it possible that a rational creature could forever hold out against the infinitely good God of love, thus damning itself? The answer to both questions is “no,” and the conclusion we ought to draw is that God will keep the door of love unlocked from his side until every rational soul, no matter how depraved it has been, finally passes through it.

Hart is happy to affirm a Thomist view of freedom. The mind guides the will by showing it the good. The more the will knows the good, the better able it is to love it. And the more a rational soul knows and loves the good, the freer it is. Very well. But the Thomist thinks it possible for this soul freely to reject God and so to incur God’s eternal wrath. That’s a contradiction, says Hart. If God is the good, only the soul clinging to God is free. The soul rejecting God is not free. And if not free, not capable of sinning in such a fashion as to warrant eternal wrath. The more thoroughly a soul rejects God the more irrational it becomes, and the more irrational it becomes the less culpable it is.

Were we to translate this into Augustine’s categories, we might say that to sin freely in such a way as to merit eternal damnation one would have already to be non posse peccare, unable to sin. Damnable sins, therefore, cannot happen and will not happen, unless of course (here’s the counter-punch) God is cruel and unjust. Which leads straight back to the existential question. Do we suppose God to be cruel and unjust? Who ever taught us to think like that? The double-predestinarians did. Their God saves and damns without respect to merit or deserts. He acts not out of goodness and love but with inscrutable power, as clearly displayed in the damned as in the redeemed. But these predestinarians are “diabolists,” not Christians, says Hart.

Those who instead say that God tries but fails to overcome the obstacles that prevent persons from arriving at full knowledge of his glory—that he then gives up and consigns them to hell—sacrifice his power without salvaging his goodness. For a God who consigns his own creatures to eternal torment falls short even of ordinary human goodness. (What decent parent would behave like that?) All ought to believe rather in the God of universal power and goodness whose grace triumphs over every obstacle and brings everyone to glory.

Hart presses the attack by asking about the nature of God. What could be better than God saving everyone? How could God do less than the best? Perhaps the God of the Greeks can do no better than to leave behind an “irrecuperable or irreconcilable remainder” of natural and moral evil, but not the Christian God, who creates freely ex nihilo. God must answer for it all, and will—not by taking out his frustration through everlasting tortures, but by universal salvation. Away with absurdities like inherited guilt and other bits of Augustinian claptrap that serve to justify the great evil remainder known as hell. Away with the notion that vessels of eternal wrath are required for the display of God’s glory! By way of these absurdities, these “sordid lies” about God, the great majority of Christian theology has descended into “sheer moral hideousness.”

Hart must absorb countless biblical body blows. The New Testament’s many passages about judgment are only metaphors, he says, “fragmentary and fantastic images” that serve as warnings against sin but say nothing of eternity in some infernal Lubyanka. By contrast, he insists, there are several passages stating plainly that God intends the salvation of all. Last-things language in the New Testament is overwhelmingly positive, at least in Hart’s translation. After he has dished out numerous examples of that translation, he appeals to Origen, whose cosmological construct can absorb almost any blow. For on that construct our conflicted age, with its horizon of impending judgment, turns out to nest inside another, the age to come, and then another and another until all conflict is resolved and eternal peace reigns.

Admittedly, that’s not the construct in the little apocalypse of the Gospels or in that big Apocalypse of John’s (to say nothing of 2 Thessalonians or 2 Peter, of which nothing is mentioned). There salvation and damnation frame the final divine act in history. The way to deal with these apocalypses, and the Gehenna passages, is simply to review the basic options: judgment as annihilation, as purification, or as eternal punishment. Neither the first nor the last will do, so purification it must be, and we must read all of Scripture in that light. It would be madness to distill doctrinal content from texts whose riotous metaphors constitute “an intentionally heterogenous phantasmagory, meant as much to disorient as to instruct.”

The Book of Revelation requires special caution, Hart thinks. Perhaps it is best read as “an extravagantly allegorical ‘prophecy’ not about the end of history as such, but about the inauguration of a new historical epoch in which Rome will have fallen, Jerusalem will have been restored, and the Messiah will have been given power”—in short, as “a religious and political fable.” Alternatively, it may be collapsing history as a whole into the cross event. Be that as it may, all these apocalyptic texts remind us that God is faithful and just. His justice will usher in the “Easter of creation” in which all shall be saved.

His toughest round behind him, Hart again denounces the “sheer moral squalor of the traditional doctrine.” He argues from the nature of personhood, using italics freely. “There is no way in which persons can be saved as persons except in and with all other persons.” We cannot “cease to care for any soul” without in principle ceasing to care for every soul, for souls exist only in webs of mutual attachment. How can every tear be wiped away without all being saved? “A person is first and foremost a limitless capacity, a place where the all shows itself with a special inflection.” We belong, in fact, “to an indissoluble coinherence of souls.” So “either all persons must be saved, or none can be.”

This is a blow struck for Gregory’s doctrine of the one Man, against the foul Augustine with his two cities and against the Thomist delusion that knowledge of the damned can actually contribute to the felicity of the redeemed. In preparation for delivering that blow, Hart briefly elaborates the idea that ignorance is the key to sin and undertakes a short digression on Romans 9–11, in which we are reminded that “all” means all and that’s all “all” means. (The gentle George MacDonald is allowed to underscore that point.)

Hart argues that God will be “all in all” only when he has completely liberated creation from the nothingness from which he began to raise it in making it exist. Hell is “merely the final, purgative completion” of that liberating process. The certainty of release from evil is already evident from the fact that evil, as a defect in something finite, is itself finite. To postulate, as the reverse side of creaturely freedom, the existence of an eternal hell is to make evil infinite, conjuring that monstrous deity who presides “over an evil world whose very existence is an act of cruelty.”

What is required, Hart believes, is a better understanding of freedom, which consists not in the power to choose but in choosing well. Until a will is fixed on God, it is not truly free and hence not truly culpable for the evil it does. Moreover, since God constitutes “the transcendental horizon” of the will, evil cannot attract us forever or hold us forever. We are divinely determined for goodness and freedom. Therefore we cannot consign ourselves to hell forever. God so arranges “the shape of reality” that all rational creatures will come upon the right path in the end and, just because they are rational, all will take it. “There may be conflicts and confusions, mistakes and perversities, in the great middle distance of life . . . but the encircling horizon never alters, and the Sun of the Good never sets.”

Under that Sun, the Incarnation demonstrates that it is no part of human nature to reject God finally. The Incarnation confirms the fact that “evil has no power to hold us and we have no power to cling to evil.” Evil, and hell with it, must disappear in the consuming fire that is God. Evil exists within our rational nature and within every soul, as Bulgakov suggests, in a dialectic with good that gradually resolves itself on God. This journey of resolution is our freedom and will make us free. To believe otherwise is not really to believe in God at all, but to believe in a sadistic devil.

Having told us what we may not believe—the “banal” doctrine of an eternal hell in which lost souls are tortured incessantly alongside actual devils—Hart now tells us what we may believe. We may believe that we came to think such blasphemous things only because we thought we had to as good sons of the Church. We may believe that the Church itself came to say such things only because they served institutional power. We may believe that the whole business is a sign of sin and psychological sickness, the very stuff of that inner Satan from which we need to be saved and of that hell we walk in every day.

How shall we score this fight? Hart does his best to make it difficult. He insists that where we think him weak or even partly mistaken it is only because we don’t understand him or because we stubbornly deny the obvious force of what he is saying. As ever, he shows flashes of brilliance, with punches thrown so quickly that we can hardly tell whether they landed. These combinations are accompanied by copious trash talk normally reserved for pre-fight hype. Our pugilist all but exhausts the world’s stock of insults, leaving his critics little to work with. Still, at the risk of entrenching a reputation for “indurated moral imbecility,” I will venture a few remarks for the home viewer.

First, be thankful that Hart has spared you the trouble of watching longer and less entertaining fights. Hart harrows “hell” with panache. And do not fault him for falling carelessly into that “error about mercy” that Augustine rejects, an error “based on human sentiment” (Augustine’s words) that sets mercy against justice. Hart is indeed sentimental, viscerally sentimental, in embracing what Augustine rejects and rejecting what Augustine embraces, but there is nothing careless about it. He thinks it right and just to do so.

On the other hand, he does not address the vital question as to whether, and how far, fallen creatures can trust their visceral feelings and instincts to guide them. Nor is he inclined to be respectful or just to his opponent. Low blows abound; holding and head-butting likewise. Is Augustine really responsible for the vicious God of the double predestinarian and for the evils of later Western determinism? Does he not make clear, in critique of Cicero, that predestination rests on foreknowledge and that foreknowledge does not entail determinism? One must not dismiss Augustine and the tradition that stems from Augustine on the basis of a moral horror that is rightly felt at certain Reformation doctrines. Besides, it is Hart’s own determinism that bears watching, the determinism of the apokatastasis doctrine.

The danger of the visceral, even the deliberately visceral, is that it too readily eviscerates reason. Hart, for example, takes every opportunity to display his outrage at the insufferable suffering of hell, hell construed as one tortured moment after another ad infinitum. But nothing requires us to understand hell in that way, as if the time of hell were merely an extension of ordinary secular time. Even if Augustine makes this mistake, as arguably he does, that does not justify Hart making it. Besides, it is absurd to say with the universalist, or for that matter with the annihilationist, that if we confine this putative succession of moments to a finite series the whole problem of insufferable suffering simply disappears. It does not disappear. What disappears, or rather what never appears, is a convincing argument.

Second, many will be perplexed, if not astonished, by Hart’s handling of Scripture. A proper argument here would require detailed exposition of enormous tracts of Scripture, which he does not attempt. Text after text—eight pages of texts—confronts the reader. But it all comes down to this: Hart takes thelei in 1 Timothy 2:4 as “intends” rather than “desires”—which is semantically possible, and contextually all but impossible. God intends, God determines, that all men be saved. He then reads the rest of Scripture in that light, demonstrating what at 1 Timothy 6:4 is called “a morbid craving for controversy.” When he finds reference to salvation for all, he does not pause to consider the covenantal and sacramental context of “all,” but insists that the meaning is “all without exception.” Where this does not seem tenable, he writes off the text in question as poetic fancy.

Others, as already intimated, will be perplexed by his handling of tradition. Tradition does not posit (even if some proponents of tradition posit) that hell exists because “there must be some real alternative to God” open to the creature. That is to misunderstand the nature of our freedom. As Anselm explains, freedom operates in the space between the will to happiness and the will to justice, both of which are given us precisely to lead us to God. What Hart describes as freedom—“freedom consists in the soul’s journey through this interior world of constantly shifting conditions and perspectives, toward the only home that can ultimately liberate the wanderer from the exile of sin and illusion”—is not a sound alternative. With this formulation, Hart builds into freedom the very thing he rightly says does not belong to it: negotiation between sin and righteousness, God and the devil.

Christology naturally gets caught up in this false negotiation. Adam represents sin and the devil (that is, the predominance of the devil within, the only devil in which Hart seems to believe). Jesus represents God and righteousness. The latter triumphs over the former, once and for all, bringing all of humanity to God. For the first man, Adam, and the second man, Jesus, are but two poles in one and the same Man, who in the course of his corporate journey at first rejects and later accepts his proper destiny. This way of thinking, which goes back to Gregory, implicates Jesus in every man’s sin, just as it imbricates every man into his salvation. Such is the price of universalism.

Hart pretends not to notice that. All he wants from his Christology is support for universalism. At one point he even tries to argue that since (a) Jesus is a man whose humanity is unimpaired, and (b) Jesus is a man incapable of rejecting God, then (c) no man to be a man must be capable of rejecting God. But (c) does not follow. And even if it did follow, it wouldn’t warrant his view that (d) no man can or will finally reject God. It is entirely orthodox, of course, to assert (c) along with (a) and (b), though not as a logical consequence of (a) and (b). It is entirely unorthodox to assert (d), which can only be maintained by running all men together into one single Man—the idealist error that has as its opposite nominalist individualism.

With this running-together, freedom ossifies and determinism sets in. We are made to love the good and so to be happy, which means to love God above all and to share God’s own happiness. But what happens when we stipulate that “made to love the good” means must love the good, unable not to love the good? Let us happily concede that man is not fully human until he does properly love the good; indeed, that his making is not complete before that point. But from that follows only that all men, if and when fully human, will properly love the good; not that all who have begun to be men will permit themselves to be perfected as men. Shall we assert the latter out of respect for the Maker? Certainly, if that is what respect for the Maker requires or even recommends as fitting. Only it isn’t. Man is a creature made to love God freely. He is not just another way of God’s loving himself.

God loves freely, not of necessity, whether he loves himself or loves us. This does not mean that God might not love himself or even that he might not love us. But it does mean that we might not love God and might therefore experience him as wrath. The point at issue is whether we might do this in perpetuity. Hart says no. We are made to love him, we must love him, and we will love him; if we don’t love him we cease to be a rational being, which he will not permit. Tradition, by contrast, says that we are made to love him, we may love him, but we might not ever love him. If we don’t, we don’t cease to be rational beings but we do cease to be rational beings at peace (Augustine again). The God confessed by the Church is transcendent enough, and the man being made by that God mysterious enough, for the “may” and the “might not.” Not so with Hart. His God sees the “might not” as defeat, and his man is not so much man as God-writ-small.

Finally, it must not be overlooked that Hart introduces a false polarity into God himself by making him responsible for evil. Creatio ex nihilo (which on Hart’s view is distinguished from emanationism by “no metaphysical difference worth noting”) is a liberation from nothingness, which is already a kind of evil. In that liberation we have being, but brute or ignorant being; and ignorant being leads to sin, for which we are culpable but never fully culpable. Out of sin we shall be trained, though the training requires more time for one man than for another. (Hart does not deal with angels; perhaps like Origen he finds no difference worth noting there, either.) Some, as it happens, will need a long spell on the purgative side of the divine fire; but that is not damnation, just a damn good roasting. All of this belongs to God’s ongoing creative-redemptive act, to the fulfillment of his original will, to the realization of his “primordial ‘ideal’ Human Being.” For created time, in whole and in part, is “nothing but the gradual unfolding . . . of God’s eternal and immutable design.”

Recall here that the whole point of Hart’s argument is to repudiate the sordid lie that God presides over a perpetual hell, like Nebuchadnezzar over his fiery furnace. But Hart is KO’d by his own argument. For hell, that evil remainder, is eradicated only by bringing it inside the primordial ideal. Are we to be horrified by the notion that God consigns anyone finally to hell—even the father of lies, if there really is a father of lies—yet not horrified by the notion that all human suffering and sin, up to and including what we call hell, belongs to the very act of creation? And are we to deny perpetuity to hell, without denying perpetuity to creation itself? What then? How shall we answer the charge laid against Origen from the start, that it must forever go round in circles—that he has by no means escaped the cyclical worldview of the pagans, on which true happiness is rendered impossible?

To be knocked out by one’s own argument is not an uncommon fate for those who set themselves over tradition rather than within it. In this case, however, there was another punch Hart didn’t see coming: the publication, just before his own book, of Michael J. McClymond’s two-volume work, The Devil’s Redemption: A New History and Interpretation of Christian Universalism. Though he appears there only in a footnote, in connection with a warm-up fight at Notre Dame, it is amply demonstrated that the problem of historical forgetfulness is Hart’s own.

No doubt the next edition of that monumental work will expand its incisive note into an appendix dismantling Hart, just as it dismantles Ilaria Ramelli’s tendentious history, The Christian Doctrine of Apokatastasis, on which Hart leans and in which Gregory is already the “hidden hero.” The immediately striking thing, however, in examining McClymond and Hart together, is that Hart’s claim to being “sufficiently novel” to forgo a proper scholarly apparatus is a hollow one. Hart’s contention that Christians before Augustine were largely universalist appears starkly as the falsehood it is. Most telling of all is the fact that McClymond’s critique of universalism—after a full account of its history from its Gnostic and Kabbalistic roots, through its earlier and later Christian stalks in Origen and Böhme, to its Enlightenment and twentieth-century flowering—is readily applied to Hart.

McClymond points out the irony that extending grace to all results in a denial of grace to any. While this happens in different ways in different universalist theories, Hart’s preference for Gregory in the early going, and for Bulgakov in the late, suggests how it happens here. For Hart, conversion is an interior purgative process, for which Adam and Christ, like Satan and even God, threaten to become mere narrative ciphers. The objective pole of grace, in the person and work of Christ, weakens as the subjective pole, in the itinerarium mentis, strengthens. Hart, it seems, is closer to certain late medieval and early modern Latin sensibilities than he realizes. The drama of salvation is reduced to a contest between light and darkness within the human soul.

Suffice it to say that anyone seriously interested in the universalist question will want to read both Hart and McClymond, albeit for different reasons: Hart to see what things look like when tradition is abandoned in favor of a private demand of conscience or personal “moral” instinct; McClymond to discover both the history and the nature of the counter-tradition to which that instinct belongs.

What is at stake between them is anything but trivial. Hart makes clear in conclusion that if Christianity requires belief in eternal punishment, then Christianity is false. Which prompts from this reporter an unhappy observation. If he really believes that, then the New Atheists, to whom he gave a thorough thrashing in earlier books, should demand a rematch. This time they might well win, and that by default.

Douglas Farrow is professor of theology and Christian thought at McGill University and the author of Theological Negotiations.