The Creation: A Meeting of Science and Religion

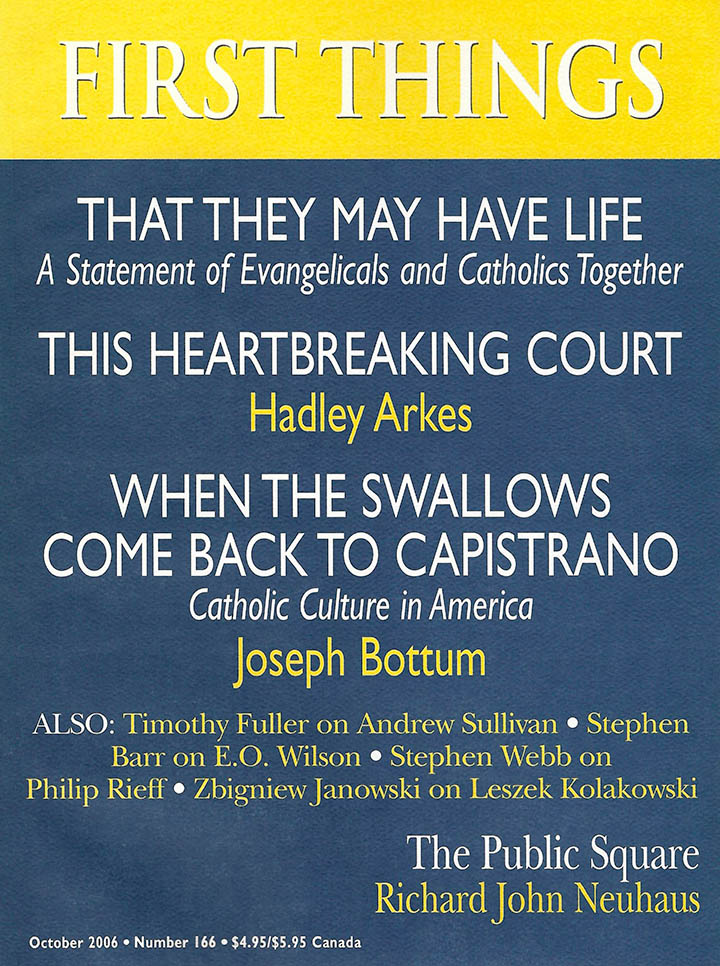

by Edward O. Wilson.

W.W. Norton, 160 pages, $21.95.

If there is a single word that sums up the life and work of Edward O. Wilson, it is naturalist. The dictionary defines a naturalist to be either “an expert in natural history; a person who makes a special study of plants or animals” or “a person who believes that only natural laws and forces operate in the world; a believer in philosophical naturalism,” and Wilson is the perfect embodiment of both. He has studied plants and animals for sixty-five years, making himself the world’s leading authority on ants. He is also the father of sociobiology, championing an uncompromising metaphysical naturalism in many of his writings. More than a mere scientist, Wilson is a devotee of the natural”which has led him in recent years to become an eloquent defender of “Living Nature” against the encroachments of man and technological spoliation.At one level, his new book, The Creation, is simply a conservationist tract, a passionate plea that we wake up to the rapid and accelerating loss of “biodiversity.” Much of the book is filled with descriptions of the astonishing variety of living things (900,000 classified species, with perhaps ten times as many remaining to be discovered) and accounts of the myriad ways in which we benefit from even the humblest of these creatures. Wilson spices up his account with many fascinating examples: [People] forget, if they ever knew, how voracious caterpillars of an obscure moth from the American tropics saved Australia’s pastureland from the overgrowth of cactus; how a Madagascar ?weed,’ the rosy periwinkle, provided the alkaloids that cure most cases of Hodgkin’s disease and acute childhood leukemia; how another substance from an obscure Norwegian fungus made possible the organ transplant industry; [and] how a chemical from the saliva of leeches yielded a solvent that prevents blood clots during and after surgery.This treasury of life is in peril. Wilson says that human activity has led the earth into “the largest spasm of mass extinction since the end of the Cretaceous period, 65 million years ago” and that this may result by century’s end in the loss of a substantial fraction of existing species.Not all the news is bad; some species have been brought back from the brink of extinction. He tells the story of the Chatham Island black robin, and the breeding of “Old Blue,” the last surviving female, with “Old Yellow,” the last surviving male. Such bright spots are the exception, however, and the picture he paints is not one to invite complacency. Yet Wilson is not an environmental absolutist or extremist. He calls himself a humanist, and much of his argument is couched in terms of the value of living nature to man”economically, aesthetically, psychologically, and even spiritually. Nor is he an enemy of technological progress and economic growth, or a crier of inevitable doom. With a one-time investment of $30

billion, he says, the world can come through the most critical period (the next hundred years) tolerably well as far as land creatures are concerned. (Preserving sea creatures will be more costly.) The Creation has as its subtitle A Meeting of Science and Religion

. Wilson has rightly been seen as an antagonist of religion, although he is not a fanatical hater of religion like Richard Dawkins. Wilson has an appreciation of the depth and complexity of human nature that leads him to what he calls “existential conservatism.” This shows, for instance, in his healthy skepticism toward the “giddily futuristic” fantasies of genetic engineering. “It is far better to work with human nature as it is . . . than it would be to tinker with something that it took eons of trial and error to create.” Consequently, Wilson does not have Dawkins’ puritanical impulse to extirpate deeply rooted aspects of human nature.Nonetheless, at a philosophical level, Wilson remains a proponent of a worldview that cannot share intellectual space with religious belief. Which makes it interesting that in The Creation , he proposes a truce. He suggests, in spite of what he sees as a deep and irreconcilable contradiction between science and religion, that they form an alliance to save the world of living things. Such cooperation is useful because science and religion are “the two most powerful forces in the world today,” and such cooperation is possible because the preservation of living nature is a “universal value.”The book is written in the form of a letter to an imaginary Southern Baptist pastor, whom he addresses as “my respected friend.” Wilson notes his own Southern Baptist upbringing in Alabama and how he once “answered the altar call” and “went under the water.” Nevertheless, there is a jarring inconsistency of tone throughout the book. The most unctuous professions of respect alternate with the most disdainful references to the Baptist’s beliefs in end-time prophecies, the torment of the damned (that will last for “trillions and trillions of years . . . all for a mistake they made in choice of religion”), and “the sacred scripture of Iron Age desert kingdoms.” Wilson speaks on one page of the “religious qualities that make us ineffably human” and on another of religion as the ignorant worship of “tribal deities.” The “respect” he has for his Baptist friend seems at times to be of the kind that a naturalist might have for an orangutan. It is a respect for biodiversity; no intellectual equality is implied. The pastor has nothing to teach Wilson except as a specimen.There is also a deep incoherence in the premise of the book. Wilson proclaims conservation a “moral precept shared by people of all beliefs” and yet avers that “the fate of ten million other [species] does not matter” for the “millions [of Americans who] think the End of Time” is imminent, a group he suspects includes his Baptist friend (“Pastor, tell me I am wrong!”). This idea of a causal link between end-time prophecy and the Religious Right’s supposed indifference to the environment has been popularized by the likes of Bill Moyers, who simply proclaim it as a fact without adducing genuine evidence and despite the vigorous denials of actual evangelicals.There is also some blame shifting in Wilson’s account. Even the unpleasant by-products of scientific progress (which, Wilson claims, has been “often opposed by the followers of Holy Scripture”) are somehow the fault of religion. After accurately describing how secular ideologies of progress have contributed to the neglect of the environment, Wilson, to lay equal blame on religion, implausibly conjures up the image of a hypothetical “religious scholar” who “might” argue for the unimportance of the “immense array of creatures discovered by science” on the grounds that they “are not even mentioned in Holy Scripture.”If Wilson knew more of the history of science, he would know that from Copernicus in the sixteenth century to Maxwell in the nineteenth, science was not “often opposed by followers of Holy Scripture” but was, in fact, largely built by them. Indeed, most great scientists in that period were such followers. But for Wilson, “science and religion do not easily mix,” and his model scientist is Charles Darwin, who “abandoned Christian dogma, and then with his newfound intellectual freedom” made his great advances. Far more typical among the founders of modern science, however, was Kepler, who announced his greatest discovery with the prayer, “I thank thee, Lord God our Creator, that thou allowest me to see the beauty in thy work of creation.”Despite his low opinion of religious thought, Wilson makes liberal use of religious language and imagery. He speaks of “the Creation” (meaning for him the world of living things), “the planetary ark,” the “redemption” of the environment, “Lazarus projects” to rescue endangered species, human life as the “mystery of mysteries,” and pristine nature as “Eden.” The word spiritual is sprinkled throughout his book. This is not just rhetoric, I think, meant to give a patina of religiosity to his ideas to make them more attractive to his imagined Baptist friend. He is up to something else, and what takes shape in the pages of The Creation , though never avowed explicitly as such, is a new religion, or a new form of a very old religion. It is naturalism writ large.Here are the tenets of this Naturalist creed: Nature is all in all. It is an “ancient, autonomous creative force,” the beneficent provider and source of life. Man is but a part of nature, and thus when we understand nature more fully we will learn “the meaning of human life” and “the origin and hence meaning of the aesthetic and religious qualities that make us ineffably human.” Indeed, human beings find their proper fulfillment in nature, since “the human species . . . adapted physically and mentally to life on Earth and no place else.” That is why we feel most at home and most serene in natural environments, especially those that most resemble the African savannah in which our species evolved.For that matter, humans have a natural “biophilia,” a love for and attraction to the rest of “living Nature.” The human race did fall, indeed more than once, and each fall involved a “betrayal of Nature.” We attempted to “ascend from Nature,” whereas what we really need is to “ascend to Nature.” In restoring and preserving living nature, we will restore Eden and experience nature’s “deeply fulfilling beneficence.” This fulfillment will be achieved in two ways: by “primal experience” of nature and scientific understanding of nature. The science of biology is the path to both: “Biology now leads in reconstructing the human self-image. It has become the paramount science . . . . It is the key to human health and to the management of the living environment. It has become foremost in relevance to the central questions of philosophy, aiming to explain the nature of mind and reality and the meaning of life.”Thus, biological science is nature understanding itself. It is a way of life. Even laymen can partake in it through scientific education, nature excursions, field trips, “bioblitzes” (in which “citizen scientists” descend upon a locale to inventory its biodiversity), and other activities that will combine recreation, education, primal experience, scientific research, and saving the planet. By serving nature, we will also bring abundant material blessings upon ourselves in agriculture and medicine.How did Wilson end up pitting science against biblical religion and erecting nature into a god? It begins with an ignorance of Western religious tradition. This reveals itself in little gaffes, as when he misuses the word magisterium, and when he innocently quotes a badly translated passage from a sixteenth-century chronicler that refers to the saints in heaven as our “lawyers” instead of “advocates.” But his theological ignorance runs deeper. He plays with the word creation, even choosing it as the title of his book, while evincing no grasp of what it means. In its traditional and profounder meaning, creation is that timeless act whereby God holds all things in existence. It is not an alternative to natural theories of origin or natural explanations of change.Just as the events of a play unfold according to an internal logic and have among themselves causal relationships, and nevertheless the whole play with all its parts has its being from the mind of the playwright, so too in the universe there are natural causes, processes, and laws, and yet the whole depends for its reality upon God. Did this insect evolve or is it created by God? To ask that is as silly as to ask whether Polonius died because Hamlet stabbed him or because Shakespeare wrote the play that way. For Wilson, nature is a play that somehow wrote itself, and, since he cannot find the author among its dramatis personae , he concludes that he must not exist.The blindness that afflicts scientists like Wilson was accurately diagnosed twenty-two centuries ago by the author of the Book of Wisdom, speaking of the physikoi of ancient Greece. “They were unable from the good things that are seen to know him who exists; nor did they recognize the craftsman while paying heed to his works . . . . Yet these men are little to be blamed, for perhaps they go astray while seeking God and desiring to find him. For, as they live among his works, they keep searching; and they trust in what they see, because the things that are seen are beautiful. Yet again, not even they are to be excused; for if they had the power to know so much that they could investigate the world, how did they fail to find sooner the Lord of these things?” In the love of nature and the preservation of nature, the Christian can join, but the Naturalism of Wilson is idolatry. Stephen M. Bar is a theoretical particle physicist at the Bartol Research Institute of the University of Delaware. He is the author of Modern Physics and Ancient Faith.