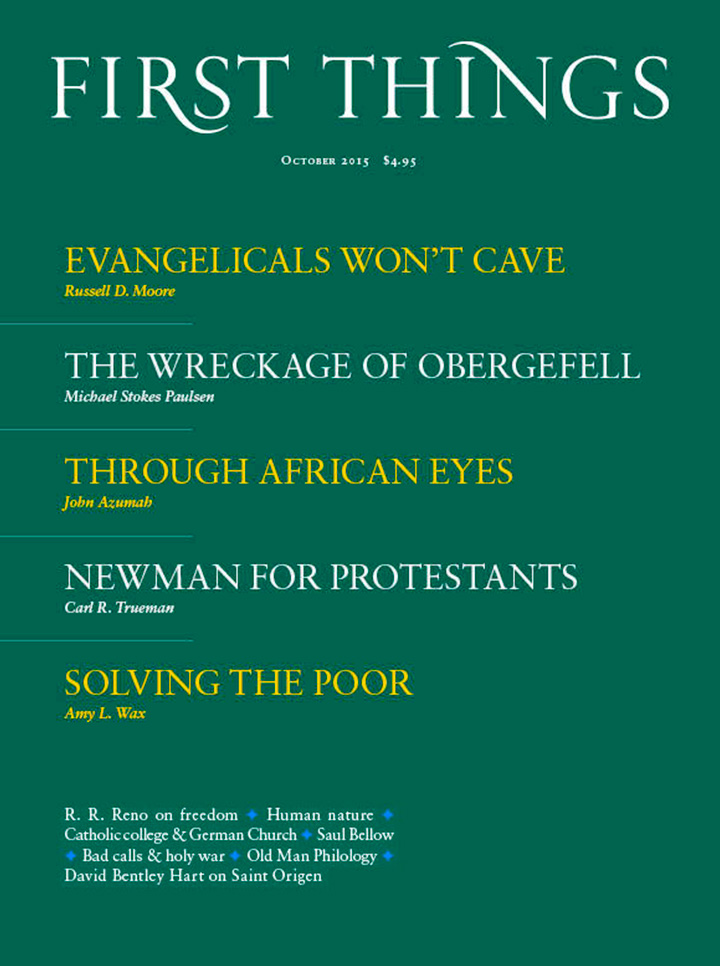

Could the next Billy Graham be a married lesbian? In the year 2045, will Focus on the Family be “Focus on the Families,” broadcasting counsel to Evangelicals about how to manage jealousy in their polyamorous relationships? That’s the assumption among many—on the celebratory left as well as the nervous right. Now that the Obergefell v. Hodges Supreme Court case has nationalized same-sex marriage, America’s last hold-outs, conservative Evangelical Protestants, will eventually, we’re told, stop worrying and learn to love, or at least accept, the sexual revolution. As Americans grow more accustomed to redefined concepts of marriage and family, Evangelicals will convert to the new understanding and update their theologies to suit. This is not going to happen. The revolution will not be televangelized.

In any given week, I’m asked by multiple reporters about the “sea change” among Evangelicals in support of same-sex marriage. I reply by asking for evidence of this shift. The first piece of evidence is always polling data about Millennial support for such. I respond with data on Millennial Evangelicals who actually attend church, which show no such shift away from orthodoxy. The journalist then typically points to “all the Evangelical megachurches that are shifting their positions on marriage.” I request the names of these megachurches.

The first one mentioned is almost always a church in Franklin, Tennessee—a congregation with considerably less than a thousand attendees on any given Sunday. That may be a “megachurch” by Episcopalian standards, but it is not by Evangelical standards, and certainly not by Nashville Evangelical standards. The church is the fifth-largest, not in the country, not in the region, not even in the city; it is the fifth-largest congregation on its street within a mile radius. I’ll usually grant that church, though, and ask for others. So far, no journalist has named more churches shifting on marriage than there are points of Calvinism. They just take the Evangelical shift as a given fact.

That presumption is a widespread case of wishful thinking. Many secular progressives believe that Evangelicals, along with their religious allies, just need a “nudge” to catch up with the right side of history, a nudge they are more than willing to provide through social marginalization or the removal of tax exemptions or various other state-mandated carrots and sticks. Our churches can simply accommodate doctrines and practices to new family definitions, these progressives advise, and everyone will be happy. Religious liberty violations, then, aren’t really harming Evangelicals, this reasoning goes, but instead are helping us to get where we’re headed anyway a little faster.

This narrative is entirely consistent with the sexual revolution’s view of itself—as progress toward the inevitable triumph of personal autonomy and liberation. As Reinhold Niebuhr put it, in the context of the New Deal, “In a democracy the crowning triumph of a revolution is its acceptance by the opposition.”

But however confident and complacent are these helpers, they can’t change the fact that the Evangelical cave-in on sexual ethics is just not going to happen. There is no evidence for it, and no push among Evangelicals to start it. In order to understand this, one has to know two things about Evangelicals. One, Evangelical Protestants are “catholic” in their connection to the broader, global Body of Christ and to two millennia of creedal teaching; and two, Evangelicals are defined by distinctive markers of doctrine and practice. The factors that make Evangelicals the same as all other Christians, as well as the distinctive doctrines and practices that set us apart, both work against an Evangelical accommodation to the sexual revolution.

The first stumbling block to any Evangelical cave-in is the Bible. Evangelicals are not “fundamentalists” in the way many have come to use the term—characterized by uniformity on secondary or tertiary doctrines along with a fighting sectarian spirit. But conservative Evangelicals are—and always have been—“fundamentalists” in the original meaning of the term, within the context of the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy of the early twentieth century. The controversy there was not over whether the millennium of Revelation 20 is literal or whether the days of Genesis 1 are twenty-four-hour solar cycles, much less over whether the King James Version of the Bible is the only legitimate English translation of Scripture.

The issues were the most basic aspects of “mere Christianity”—the virgin birth, the miracles, the atonement, the bodily resurrection, and the inspiration of Scripture. The Evangelical commitment to biblical authority means that the Bible is not written by geniuses but by apostles, to use Kierkegaard’s distinction. The words of the Bible are breathed out by the Spirit, as the apostle Paul puts it (2 Tim. 3:16). “For no prophecy was ever produced by the will of man,” the apostle Peter teaches. “But men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Pet. 1:21).

The Reformation principle of sola scriptura does not mean, as it is often caricatured by non-Protestant Christians, that the only authority is the Bible and the individual Christian. It means instead that the only final authority is the prophetic-apostolic word in the writings of Scripture. If an Evangelical needs driving directions to Cleveland, she consults Google maps, not her concordance. If, though, Google tells her that first-century Judea was uninhabited, she knows Google is wrong. The authorities here conflict, and Scripture trumps other authorities, not the other way around.

It’s also not accurate to say that sola scriptura negates church authority or the necessity of tradition or a teaching office. The most vibrant sectors of American Evangelicalism are those most committed to creedal definition and to a disciplined church. Evangelicals, though, do not believe in a “once saved, always saved” sort of eternal security for any particular institutional church. A church can lose the Gospel and with it the lampstand of Christ’s presence (Rev. 2:5).

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the Evangelical view of scriptural authority, a persistent cultural pattern has emerged from it. Evangelical Protestants are always aware of the possibility of false teachers. They judge every human teacher or teaching against the text of Scripture. This by no means is foolproof—see the heresies of prosperity gospel teaching, for just one example—but it does mean that innovators must be especially cunning, able to explain their views in a way that does not seem out of step with the Bible—if they are to win a long-term hearing among Bible-believing Evangelicals.

Revisionist arguments will not work among conservative Evangelicals because people read the texts, and the biblical texts—as orthodox believers and antagonistic unbelievers agree—hold to a vision of marriage and sexuality wholly out of step with post-Obergefell America.

Revisionists get around that flat conflict by citing a context for the text, asserting the difference between ancient and modern notions of sexual orientation. But, Evangelicals reply, the definition of marriage is not grounded in ancient Near Eastern culture but in the created order itself (Gen. 2:24). That’s why Jesus speaks of man-woman marriage and its permanence as “from the beginning” (Mk. 10:6). Moreover, the canon asserts that even this natural “one-flesh union” points beyond nature to the blueprint behind the cosmos, the mystery of the union of Christ and his Church (Eph. 5:32).

Much has been made in media circles of Evangelical dissenters from traditional orthodoxy on questions of sexual ethics. These dissenters, however, are not leaders known for Bible-teaching or church-building or institution-leading. They are known for the dissent itself. In virtually every case, the high-profile “Evangelicals” who have shifted on sexual ethics were already theologically liberalized on multiple other issues, often for decades. An “Evangelical” who attends a mainline, liberal Protestant church or who shares platforms with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence is not likely to be received as an Evangelical by Evangelicals.

Journalists covering such dissenters should ask them these basic questions: Where do you go to church? What do you believe about the inerrancy of Scripture? Is there a hell, and must one believe consciously in Christ in order to avoid it? They cannot portray these figures as representative Evangelicals unless they give certain answers. I would bet that a little probing would show that these stories are the equivalent of writing an article about the Democratic party’s views on foreign policy by citing hawkish independent-Democratic former U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman.

In his commentary on Paul’s Letter to the Galatians, the late Anglican Evangelical John R. W. Stott offers a prescient point relevant to this issue. It turns on Paul’s defense, in the opening chapter of the letter of his apostleship, of his genuine witness to the risen Christ and his authority to speak on Christ’s behalf by the Spirit. Against Paul were the “super-apostles” who sought to divide Paul from the original apostles in Jerusalem and even from Jesus himself. This contest did not end with the apostle’s beheading in Rome, Stott observes, nor with the close of the canon.

“The view of modern radical theologians can simply be stated like this: The apostles were merely first-century witnesses to Christ. We on the other hand are twentieth-century witnesses, and our witness is just as good as theirs, if not better,” Stott wrote. “They speak as if they were apostles of Jesus Christ and as if they had equal authority with the apostle Paul to teach and to decide what is true and right.”

The sexual revisionists within Evangelicalism appeal not merely to the priesthood of all believers. They appeal to the apostleship of all believers, something orthodox Christians of all branches reject. It underlies the crux of the revisionist argument: that the apostles did not know what we know now about sexual orientation.

The fact that homosexuality—and other forms of sexual immorality—is always and everywhere spoken of negatively in Scripture is explained away by a lack of scientific knowledge about loving, monogamous same-sex unions, the immutability of sexual orientation, or something else. Such arguments make sense if the authority of Scripture rests in the expertise of the apostles and prophets themselves. If, on the other hand, the authority of Scripture rests in the Spirit inspiring and carrying along the authors, the arguments collapse. If the Bible is a coherent book, with an Author behind the authors, one can hardly say that God is ignorant of contemporary knowledge about sexuality.

The revisionist position stands, then, not on an interpretation of the words of Scripture, but on a choice of who is the author of them. The revisionists are not only teachers; they are apostles, too. They can pronounce the meaning of Christ just as the first-century apostles did. The revisionists most often wish to keep the attention on Moses and Paul, pointing to the fact that Jesus said nothing about homosexuality. Of course, by defining marriage in terms of male–female complementarity and by affirming the moral teachings of the Torah, Jesus did speak to the issue. Not only that, but Evangelicals don’t set the words of Scripture not explicitly uttered by Jesus in so malleable a condition. If “all Scripture” is breathed out by the Spirit (2 Tim 3:16), and if the Spirit inspiring the biblical authors is the “Spirit of Christ” (1 Pet. 1:10–11), then every text of Scripture is Jesus speaking, not just those that publishers code out in red letters.

Increasingly, though, revisionists have to deal with Jesus himself. Journalist Brandon Ambrosino argued that the best argument for same-sex marriage is that Jesus was simply wrong about marriage, owing to the fact that he was ignorant of contemporary scientific notions of sexual orientation and the evolving standards of a morality of love. It takes quite a messiah complex to school the actual Messiah on moral and ethical truth, all while claiming to follow him. This argument is immediately off-limits for Evangelicals because they are, first of all, “mere Christians” who agree with Nicaea and Chalcedon about who Jesus is. The argument that “Jesus would agree with us if he’d lived to see our day” won’t work for people who know that Jesus is alive today—and that his views aren’t evolving (Heb. 13:8).

Some would say, though, that even if the Bible can’t be easily made to fit into a sexual revolutionary matrix, the culture will change quickly enough to make traditional Christian sexual ethics implausible. The Church will adapt to same-sex marriage the way the Church adapted to divorce. Pastor Danny Cortez, for instance, who was dis-fellowshipped from the Southern Baptist Convention for moving his church to a “welcoming and affirming” position on homosexuality, argued that Evangelicals have already moved in this direction on divorce and remarriage. Few celebrate divorce in theory, but there are many divorced and remarried people in our pews, sometimes even in our pulpits. There’s some truth to this. I’ve argued for years that too often Evangelical churches are filled with “slow-motion sexual revolutionaries,” adapting to where the culture already is, simply ten or twenty or thirty years behind. Divorce is all too common in Evangelical congregations, even the most conservative ones. But divorce does not show us the future as it relates to the current controversies over marriage and sexuality.

First of all, most Evangelicals (unlike Roman Catholics and some other groups) believe there are some instances in which divorce and remarriage are biblically permitted. Most Evangelical Protestants acknowledge that sexual infidelity can dissolve a marital union and that the innocent party is then free to remarry. The same is true for abandonment (1 Cor. 7:11–15). Disciplined churches that held couples accountable to their vows would see far fewer of these situations, but, still, remarrying after divorce is not, on the face of it, sin in an Evangelical perspective, and never has been.

Beyond that is the question of what repentance looks like. In an Evangelical Protestant view, a remarriage after a divorce may well constitute an act of adultery, but the marriage itself is not, in the view of most Evangelicals, an ongoing act of adultery. Even if these marriages were entered into sinfully in the first place, they are in fact marriages. Jesus spoke of the five husbands of the woman at the well in Samaria, and differentiated them from the man with whom she lived, who was not her husband (John 4). Same-sex unions, which do not join male and female together in the icon of the Christic mystery, do not constitute marriages biblically. Repentance, in this case, looks the same as it does for every other sexual sin—fleeing from immorality (1 Cor. 6:18).

A better example for the future shape of this debate is that of “Evangelical feminism.” In the 1970s and 1980s, a movement gained steam in Evangelicalism to read biblical texts on gender in a more egalitarian way. These feminist groups stood with other Evangelicals on biblical inerrancy (and on the prohibition against homosexuality) but argued for women’s ordination. They wrote scholarly books and articles on why the apostolic prohibitions on women “teaching and exercising authority over men” (1 Tim. 2:12) were culturally conditioned, addressing specific problems in the first-century churches rather than timeless prescriptions for the Church. Several years ago, I argued that although I strongly disagree with it, I thought Evangelical feminism would win the day in American Evangelicalism. The cultural currents were simply too strong, I thought.

I was wrong. It is now hard to find leaders of Evangelical feminist organizations who are recognized by the rest of the movement as solidly conservative and orthodox. The ones who speak up and often about gender are those with “complementarian” (traditional) views. The largest Evangelical denominations and church-planting organizations and conferences are now complementarian (in a way that wasn’t true at all just a decade or two ago). What happened? The center of gravity in Evangelicalism moved from “seeker sensitive” pragmatism to a yearning for connection to older, theologically robust, confessional traditions, which often had developed theologies of gender. Moreover, the “slippery slope” from Evangelical feminism to heterodoxy proved to be real. More and more Evangelical feminists applied their gender views to sexuality in ways clear enough for conservative Evangelicals to see it as a rejection of biblical authority.

It is not the case that gender egalitarians challenge Christian orthodoxy at the same fundamental level as same-sex marriage revisionists do. I disagree with these egalitarian arguments, but they have a far stronger case for their views than the sexual revisionists, both in terms of the biblical text (examples of women leaders such as Deborah the judge and the joint inheritance of men and women in Christ, etc.) and in terms of the history of the Church (some orthodox groups in, for instance, the Wesleyan and Pentecostal wings of the Church had women preachers and leaders long before the modern feminist movement). Yet if Evangelicalism can withstand the strong cultural tides of feminism—even in its most popularly palatable forms—Evangelicalism can do the same with the even more clearly defined issues of sexual morality.

The Christian sexual ethic is controversial, to be sure, and in different ways at different times, it always has been. But it’s not the most controversial thing orthodox Christians believe. That would be the doctrine of hell. In almost every generation of the Church, someone seeks to negotiate away the doctrine of hell through a universalism that sees to it that judgment will not fall on sin. Churches that embrace universalism typically start out on that path with exuberance, as they are freed from the shackles of guilty consciences and fears of eternity. But those churches quickly wither and die. There are no universalist megachurches, no universalist church-planting movements. That’s because consciences are not burdened with an externally imposed eschatology; consciences are pre-loaded with an eschatology. The law written on the heart, the Apostle Paul writes, informs the conscience which “bears witness” toward the day when “God judges the secrets of men by Christ Jesus” (Rom. 2:15–16).

What the sexual revolution’s revisionist ethic asks is that the Church adopt a pinpointed surgical-strike universalism, one that denies that judgment is coming for this one particular set of sins. As with any form of universalism, this doesn’t liberate people, but rather enslaves them to their own accusing consciences. Even if we can excise what the revisionists call “clobber verses” from the Bible, we cannot overpower the witness of the conscience.

Will some high-profile Evangelicals cave on a Christian sexual ethic? Yes, of course, a few will. Some Evangelical leaders are entrepreneurial and driven by pragmatism and a need for relevance. Others use Evangelicalism the way an aging rock star uses the country music audience when he’s too old for top-40 radio. They make a living peddling mainline Protestant shibboleths to Evangelical markets because, after all, that’s where the money is. But, as the apostle Paul says of the Egyptian magicians Jannes and Jambres and of the false teachers in the first-century church at Ephesus, “They will not get very far, for their folly will be plain to all” (2 Tim. 3:9).

Secularization and sexualization have put orthodox forms of Christianity on the defensive, especially the most culturally odious form of Christianity, conversionist Evangelicalism. This not only changes the nature of the Church’s mission field; it also clarifies the Church’s witness. What previously could be assumed must now be articulated.

For nearly the past two centuries, Evangelicals, especially in the South and Midwest, could count on the culture to do a kind of pre-evangelism. The culture encouraged people to aspire to a kind of God-and-country citizenship, to marriage, and to stable family life. Even when people didn’t live up to those ideals, they knew what they were walking away from. Evangelicals, then, could use “traditional family values” to build a bridge to people for the Gospel. Churches could plan on crowds to hear counsel for a better marriage, or how to put the sizzle back in a sex life, or how to discipline toddlers or maintain a good relationship with one’s teenagers. One could trust that the culture shared the “values.” People just needed practical tips on how to achieve those values, starting with “a personal relationship with Jesus.”

We can no longer assume, even in the Bible Belt, that people aspire to, or even understand, our “values” on marriage and family. These parts of our witness that were the least controversial—and could be played up while playing down hellfire and brimstone, for those churches wanting a softer edge—are now controversial. Churches that reject the sexual revolution are judged as bigoted. Churches that don’t won’t fare much better, for in a secularizing culture, churches that embrace the revolution are unnecessary—just as the churches that rejected the miraculous in favor of scientific naturalism were in the twentieth century.

In post-Obergefell America, Evangelicals and other orthodox Christians will be unable to outrun our freakishness. That is no reason for panic. Some will suggest that a Christian sexual ethic puts the churches on the “wrong side of history.” Well, we’ve been on the wrong side of history since a.d. 33. The “right side of history” was the Eternal City of Rome. And then the right side of history was the French Revolution. And then the right side of history was scientific naturalism and state socialism. And yet, there stands Jesus still, on the wrong side of history but at the right hand of the Father.

If we are right about the end of human sexuality, then we ought to know that marriage is resilient. The sexual revolution cannot keep its promises. People think they want autonomy and transgression, but what they really want is fidelity and complementarity and incarnational love. If that’s true, then we will see a wave of refugees from the sexual revolution, those who, like the runaway son in Jesus’ story, “come to themselves” in a moment of crisis.

Churches so fearful of cultural marginalization that they distort or ignore the hard truths of the Gospel will not be able to reach these refugees. Churches that scream and vent in perpetual outrage won’t, either. It will be of no surprise if the churches most able to reach those wounded by sexual freedom, and the chaos thereof, will be the churches most out of step with the culture. Whatever one thinks of the “temperance” of many wings of American Evangelicalism, it is no accident that so many ex-drunks, and their families, found themselves walking sawdust trails to teetotaling Baptist and Pentecostal churches, not to the wine-and-cheese hour at the respectable downtown Episcopalian church.

The days ahead require an Evangelicalism that is both robustly theological and warmly missional, both full of truth and full of grace, convictional and kind. This does not mean a kind of strategic civility that seeks to avoid conflict. The kindness that is the fruit of the Spirit is of the sort that “corrects opponents,” albeit with gentleness and patience (2 Tim. 2:24–25). A Gospel-driven convictional kindness will not mean less controversy but controversy that is heard in stereo. Some will object to the conviction, others to the kindness. Those who object to a call to repentance will cry bigotry, and those who measure conviction in terms of decibels of outrage will cry sell-out. Jesus was controversial among the Pharisees for eating at tax collectors’ homes, and he was no doubt controversial among the tax collectors for calling them to repentance once he arrived there. He sweated not one drop of blood over that, and neither should we.

While I am not worried about Evangelicals’ caving on marriage and sexuality in post-Obergefell America, I am worried about Evangelicals panicking. We are, after all, an apocalyptic people, for good and for ill. We can wring our hands that the world is going to hell, but then we ought to remember that the world did not start going to hell at Stonewall or Woodstock but at Eden. Adam was our problem, long before Anthony Kennedy. Mayberry without Christ leads to hell just as surely as Gomorrah without Christ does. We cannot respond pridefully to the culture around us as though we deserve a better mission field than a sovereign God assigned to us.

This means that Evangelicals can best serve the culture by being truly Evangelical. We are not in a “post-Christian” America, unless we define “Christian” in ways that disconnect Christianity from the Gospel. The mission of Christ never calls us to use nominal Christianity as a bridge to redemption. To the contrary, the Spirit works through the open proclamation of truth (2 Cor. 4:1–2). It is the strangeness of the Gospel that confounds the wisdom of the world, and that actually saves (1 Cor. 1:18–31). The Gospel does not need idolatry to bridge our way to it, even if that idolatry is the sort of “Christianity” that is one birth short of redemption. Our frame of reference is not happier times in the 1770s or 1950s or 1980s. We are not time travelers from the past; we are pilgrims from the future. We are not exiles because American culture is in decline. We are exiles and strangers because “the world is passing away, along with its desires” (1 Jn. 2:17).

I don’t think American Evangelicals will fold on our sexual ethic. But if we do, American Evangelicalism will have nothing distinctive to say and will end up deader than Harry Emerson Fosdick. If so, the vibrant Evangelical witness God has called together in Nigeria or Argentina or South Korea or China will be alive and well and ready to send missionaries to preach the whole Gospel. Whether from America or not, a voice will stand, crying in the wilderness, “You must be born again.”

Russell D. Moore is president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention and author of Onward: Engaging the Culture Without Losing the Gospel.