The cry of lament in Psalm 102 exposed a raw wound: “My days pass away like smoke and my bones burn like a furnace.” I had been diagnosed with an incurable blood cancer, which had already burned away bone from inside my skull, an arm, and a hip. Thinking of my children (ages one and three), I found that the psalm expressed my most intimate, desperate prayer: “Do not take me away at the midpoint of my life, you whose years endure throughout all generations.”

Within a week of my diagnosis, I began a regimen of chemotherapy and steroids, five months of preparation for a stem-cell transplant. “Transplant” is a misnomer; the treatment is a lethal dose of chemotherapy followed by a rescue plan. After stem cells were withdrawn from my blood and frozen, I received high doses of a chemotherapy derived from mustard gas. Then the stem cells were infused back into my body, in the hope that they would start regenerating my immune system. The procedure requires a month in the hospital and three months in quarantine.

There were times I was grateful for God’s many gifts. Thanks be to God, my stem-cell transplant lowered my cancer levels, and my immune system eventually reactivated. Yet the good news had a surprising impact. My grieving worsened. Psalm 102 described me well: “I lie awake; I am like a lonely bird on the housetop.”

I lay on my bed in a cancer lodge for quarantined patients, crying aloud, when the thought came to mind: My life would never be the same. There will be “maintenance” chemo treatments for as long as my remission lasts, because the cancer is expected to return. When it comes back, I will need more-intensive treatment using different toxins (relapsed cancer is harder to treat). As I anticipated returning to normal life, I felt more alienated than ever. How was I to respond to ordinary questions like “How are you?” and “How have you been?” How was I to look with hope toward the future—for my family, for my vocation? I feared for my children. Would they lose their father midcourse in their childhood?

During my treatment, two friends with cancer reached the end of the line, moving from experimental chemotherapy to palliative care, to dying, to death. It all happened so quickly. I was in remission, but for what? To wait around for this to happen to me, just as it had happened to my friends? At certain moments, while other people’s lives were moving ahead at full speed, mine seemed to be spinning in the direction of my dying and dead friends. Rather than reentering into my previous, purposeful life, joyous at my recovery, I felt “forsaken among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave” (Ps. 88:5).

The sharp leg pain and intense nausea from earlier stages of my treatment waned, and my immune system was slowly coming alive again. I received notes and calls from friends who rejoiced at the news of my progress. I rejoiced with them, but I was grieving inside. My news was good—why was I grieving? It didn’t seem fitting that I would mourn at this point in the process, just when it looked like I’d passed through the valley of death and returned to regular life. Sometimes suffering feels like a free fall rather than a swing down to the valley on a rope that will bring us back up to safety.

“During the days of Jesus’ life on earth, he offered up prayers and petitions with fervent cries and tears to the one who could save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverent submission” (Heb. 5:7). These words were a consolation to me. My own “fervent cries and tears” were not blazing new trails into grief; I was not a pioneer in the darkness. An existential fear at the prospect of death had gripped me, but there was also a Spirit-enabled sharing in the One who has plunged even deeper into the darkness.

When Christ on the cross laments with the Psalmist, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” his desolation means that when we pray this ourselves, we are not in a free fall, even when it feels that way. We can utter a cry of unspeakable anguish and yet maintain a profound hope, because, in Christ, God himself has taken on our human suffering, including our alienation and dread. As the Heidelberg Catechism testifies, Christ’s suffering and lament “assure me during attacks of deepest dread and temptation that Christ my Lord, by suffering unspeakable anguish, pain, and terror of soul, on the cross but also earlier, has delivered me from hellish anguish and torment.” In the words of Ambrose, “Even as His death made an end of death, and His stripes healed our scars, so also His sorrow took away our sorrow.”

As I look back, I can see I received comfort, support, and reassurance in Christ’s suffering, but not in the way suggested by trends in recent academic theology and popular Christian piety. We’ve all heard messages like these: Since God is relational and loving, God is “suffering with me.” Or, God is in such solidarity with sufferers that he simply identifies with us in our calamities. Or, Christ’s suffering expressed something called “divine suffering,” an essential part of God’s identity.

This way of thinking about God and suffering was not good news during my ordeal. In the midst of my daily shots, sharp headaches, and heavy fatigue, these reflections on God and suffering didn’t console me. They troubled me. They didn’t encourage hope that I was not in a free fall. If Christ’s suffering does not triumph over death’s claim to have the final say over life, then I might as well give up. If the suffering of Christ is not, finally, a revelation of the triune God’s faithful, impassible love, then the cross could no longer be my solace in the midst of my physical agony and existential despair.

As strange as it may sound, I found myself clinging to a different sense of God’s saving solidarity with us: the doctrine of divine impassibility. As I felt my life drained by the cancer, I took profound comfort in this doctrine that God’s power of life suffers no limits. As the Letter of James puts it: “Every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of the heavenly lights, who does not change like shifting shadows.” The doctrine of impassibility affirms God’s steady, indomitable love. He has the backbone to take on our terror and overcome it in Christ.

The doctrine of divine impassibility is the belief that God has no “passions”—that is, no disordered affections that could make his love ebb and flow. He delights in the goodness of creation and in obedience, has compassion for the suffering and hears their cry, grieves over the creation’s self-destructive sin, and is angry at evil, injustice, and wickedness. But the Lord who freely enters into covenantal relationships with creatures is never blindsided or manipulated by them. Instead, God loves in fullness. In this way, the doctrine of impassibility holds together two truths at once: While it is true and right to say that God loves, delights, grieves, and is jealous, there is also a fundamental difference and distinction between God’s affections and our own creaturely ones. Unlike our own emotional lives, God’s affections are never distorted through sinful, disordered passions, nor are they controlled by greater powers.

My grief over my illness was a function of my bodily vulnerability to sickness and death. The love, grief, wrath, and jealousy that we see in other humans are always tinged with outer influences. When tragedy hits, we reel in surprise and dismay. I did exactly that, and felt myself in free fall. You might say I was not myself.

In contrast, God’s affections are always in accord with his holy and gracious character. They are perfect, self-derived expressions of his faithful covenant love. While our emotional responses are often manipulated by others, or caused by circumstances that make us act “not like ourselves,” God is never less than true to himself. Thus, the fundamental difference between God’s affections and our own is rooted in the reality that God is God and we are not. Yes, God condemns human jealousy (1 Cor. 3:3), but God is righteously jealous when his people engage in idolatry (Exod. 20:5). His response is not like a human expression of jealousy, because God is not wounded or at a loss. In his delight, grief, wrath, and jealousy, God acts in and is perfect, untainted love.

Portrayals of the classical Christian teaching of divine impassibility often slide into caricature, presenting God as apathetic and unresponsive. Rightly construed, God’s impassibility is just the opposite. As Paul Gavrilyuk notes, “It is precisely because God is impassible, i.e., free of uncontrollable vengeance, that repentant sinners may approach him without despair. Far from being a barrier to divine care and loving-kindness, divine impassibility is their very foundation.” A healthy doctrine of divine impassibility emerges from a biblical meditation on God’s love. It is not a notion imported wholesale from Greek philosophy, as many claim, but rather was refined through debates about biblical exegesis as the Church in the fourth and fifth centuries developed the ecumenical confessions about the Trinity and Christ. That is why, when the Council of Chalcedon affirms the integrity of Christ’s two natures, it also condemns priests who “dare to say that the divinity of the Only-begotten is passible.” In the witness of John’s Gospel to the Incarnation of the Son, “the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.”

The doctrine of divine impassibility reflects the Old Testament testimony to God’s faithful, covenant love. It was developed to protect the integrity of the New Testament witness to the deep paradoxes of the great and transcendent God who takes on humanity in the birth, life, death, and resurrection of Christ—at once truly God and truly human in one person. Creator and creature are confessed as distinct yet united in the person of Christ. Thus, as Gavrilyuk explains, “God, as God, does not replicate what we, as humans, suffer. Yet in the Incarnation, God, remaining God, participates in our condition to the point of the painful death on the cross. Remaining impassible, God chooses to make the experiences of his human nature fully his own.”

The topic of divine impassibility came up a surprising number of times in responses that I received to my illness. I recall a greeting card with printed text from a well-known Evangelical author who sought to provide reassurance—“Does God hurt when you do? Absolutely.” I know what the person sending the card was seeking to say: “God knows you with intimacy in your suffering, and has compassion on you in suffering.” But the card actually said something else, a variant of a too common view that “God is suffering with you.” The message envisions a God who just reflects and mirrors what I’m feeling—like a Rogerian therapist. It sounds as if God was trembling in hurt and surprise from cancer just as I was. Apparently, all that the suffering person needs is a God of identification and solidarity, one who says, “I feel your pain.”

But this identification (God “hurting” with me) is not a true one. As I came to realize in a powerful way during my treatment, pain and suffering are never less than a bodily reality. I’ve experienced too much of it to believe otherwise—the sharp pain of mouth sores, the exhaustion of deep fatigue, the sting of another injection. And it’s true of my emotional pain, too. When I was in anguish for the sake of my young children, this was not just a “thought” hovering above me, but an experience of my whole body—tightened muscles, shallow breath, and tears.

As Elaine Scarry puts it in The Body in Pain, “Physical pain has no voice.” Of course, we seek to express our pain—with cries, metaphors, stories—but those linguistic expressions always fall short. Human suffering is inseparable from bodily pain. It’s not just an “idea” that can float free of a body.

This should give us pause when we too quickly speak of God’s suffering. Is a human body a part of God’s divine nature? If we say no, then the flat assertion that “God suffers” becomes a mere abstraction, a dark enigma, not an illuminating mystery. The notion of God-as-Spirit suffering in a nonbodily or nonhuman way provides me no solace, no companionship, no identification. I believe that God knows me in my suffering, with a perfect, loving intimacy. But to say “God suffers with me” leaves me isolated in my bodily suffering.

Thankfully, for the vast bulk of church history, Christian teaching has insisted that in the Incarnation the Son assumes human suffering and death in order to conquer suffering and death—emptying them of their finality. In a sense, it is true that God embraces us in our suffering, and does so with perfect compassion. In Christ, we see a fulfillment of the Suffering Servant portrayed in Isaiah: “a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief” (53:3). In Christ, we have a High Priest who is able “to sympathize with our weaknesses” (Heb. 4:15). God identifies with human sorrow, grief, and suffering. But our hope is not that God is overtaken by suffering in the same way that we are. We hope because, in Christ, God has taken on human suffering and death, so that they are denied their power to define our lives.

When we locate suffering in the mystery of the Incarnation, we move toward paradoxical words of worship. As Charles Wesley wrote in his beloved hymn:

Amazing love! How can it be,

That Thou, my God, shouldst die for me?

Amazing love! How can it be,

That Thou, my God, shouldst die for me?

’Tis mystery all: th’Immortal dies:

Who can explore His strange design?

In vain the firstborn seraph tries

To sound the depths of love divine.

Wesley’s paradox hinges on the union of a holy, transcendent God with the suffering, dying humanity of the person of Jesus Christ. The Creator takes on human flesh, uniting himself to it, dwelling among us as the perfect embodiment of God’s covenant law and promises, becoming “obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross” (Phil. 2:8). In this way, the triune God “reconciled us to himself through Christ” (2 Cor. 5:18).

It is therefore essential for us to affirm that God is still God in the suffering flesh and soul of Christ. As Gregory of Nazianzus put it, in the Incarnation, God the Son “remained what he was; what he was not, he assumed,” and “what is united with God is also being saved.” Thus, our suffering in all of its messy bodiliness is redeemed, because God has assumed a bodily, human suffering in the Incarnation. “He is weakened, wounded—yet he cures every disease and every weakness.” Amid my cancer treatment, doctors have poked and prodded my body dozens of times, covering me with bruises. But there is One whose bruises bring healing, and even my “incurable cancer” is not beyond his reach.

In a famous and influential move away from divine impassibility, Jürgen Moltmann insists that when Jesus laments on the cross, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” there is a separation between the Son and the Father, an “abandonment.” “What happened on the cross was an event between God and God,” he says. “It was a deep division in God himself.” He makes this claim in order to rethink the doctrine of God after Auschwitz. But by asserting that the Father abandons the Son on the cross, Moltmann denies the way Jesus’s cry from Psalm 22 establishes solidarity with those who suffer. When Jews and Christians have cried out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” they have done so with the belief that God will not forsake his suffering people, not that they have been abandoned.

When he makes suffering internal to the divine nature, Moltmann describes not a God of genuine love who freely enters into covenant with creatures but rather a God who “loves” us as part of a divine self-realization project. As David Bentley Hart argues, if we require God to suffer in his own nature in order to be a loving God, “goodness then requires evil to be good; love must be goaded into being by pain. In brief, a God who can, in his nature as God, suffer cannot be the God who is love, even if at the end of the day he should prove to be loving.” In rejecting divine impassibility, theologians such as Moltmann expound the idea that “God is love” (1 John 4:8) without remembering that the same biblical book insists that this same God is also “light, and in him there is no darkness at all” (1 John 1:5).

There is a rich irony here, one that I became acutely aware of while undergoing treatment. Many modern theologians depart from the classical Christian tradition to seek after a “kinder, gentler” God—one with a “reciprocal” relation to the world. But such a God is not truly merciful. He may model “relationality” in ways that charm academic audiences, but he is useless for sufferers desperate for deliverance, those who cry to God out of the depths. Moltmann romanticizes suffering by making it an essential part of God’s life, as if empathy were enough to redeem those who need a sovereign Lord.

In the hospital, I didn’t need just solidarity in my suffering. I needed to know that God’s covenant love is so steady and powerful that, in Christ, suffering and death lose their dominion over my life. This God does not need suffering and death in order to be God; instead, in the love that accords perfectly with his covenantal promises, God becomes incarnate as the Pioneer, our Brother, the great High Priest who in his humanity is able to “sympathize with our weaknesses” (Heb. 4:15). This is not “a deep division in God himself.” This is steadfast, trustworthy love.

In the dark time of my cancer treatment and recovery, I rediscovered the importance of Paul’s prayer for the Ephesians: that we “may have the power to comprehend” the “breadth and length and height and depth” (3:18) of Christ’s love. God’s love is not as frail as our love. It “surpasses knowledge.” God’s is a covenant love that the Psalmist trusts in the midst of his anxiety, joy, anger, and misery. It is the steadiness of God’s love that allows us to approach him amid the unsteadiness of our anguish and frailty.

I have become increasingly openhanded in my prayers, hopeful in a generous and loving God—even when he doesn’t seem to follow the instructions of my petitions. Like Job after his restoration, I realize the risks of loving others, given our all-too-human fate of suffering and eventual death. Yet, I have emerged with a deeper trust in God’s loving promise, because unlike human beings who constantly toss and turn, fabricating and prevaricating, forgetting their promises, “it is impossible for God to lie” (Heb. 6:18).

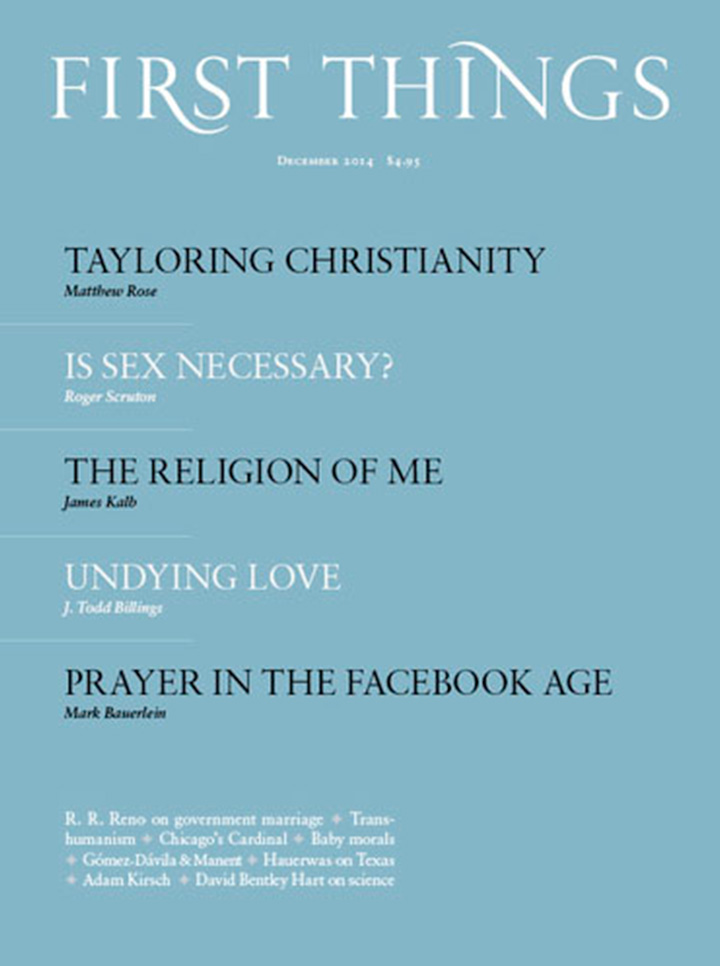

J. Todd Billings is the Gordon H. Girod Research Professor of Reformed Theology at Western Theological Seminary in Holland, Michigan. This article is adapted from his forthcoming book, Rejoicing in Lament: Wrestling with Incurable Cancer and Life in Christ (Brazos Press).