I retired from the University of Notre Dame at the end of 2025. More accurately, I left. After twenty years on the faculty, I could no longer do Notre Dame. So I’ve bailed, without being sure what will come next.

My leaving Notre Dame might seem unusual. I’ve only just turned sixty-five. I am active in research, publishing some of the best work of my career. I loved teaching Notre Dame undergraduates. I held a Kenan endowed chair, which provided a nice research fund. I earned an enviable salary. Almost any faculty member similarly situated would continue working five, ten, or fifteen more years.

And I was an ideal fit, the kind of academic Notre Dame should want on staff: an accomplished scholar who won awards as a classroom teacher and student mentor. Over the years, I brought in $15 million in external research grants. I was dissertation chair for the best-placed PhD graduate in Notre Dame’s history, now a full professor at Yale. I was an enthusiastic proponent of the university’s Catholic mission. I was devoted to my discipline, sociology, but also engaged ideas in philosophy, history, theology, and political theory.

But after two decades, I left. Not happily, not with a sense of fulfillment or closure, but disappointed and vexed. Why? And what might my experience reveal about the bigger picture?

When I came to Notre Dame, I believed the university was serious about its Catholic mission. I tried to make my contribution, I think with some success. But I also saw much of the institution absorbed by other interests that, in my view, were often irrelevant to or at odds with the Catholic mission. Most demoralizing was the leadership’s lack of vision and courage.

Above all else, a university is a community of scholars. Among themselves and with their students, faculty confront important intellectual questions within and across their disciplines, in pursuit of knowledge about what is real, good, true, beautiful, and beneficial. Their task involves mastering received academic traditions, inquiring into their key questions, and introducing new generations to that same project.

We live in a pluralistic society, and so the work of scholarship can and should be pursued within diverse, distinctive intellectual traditions—secular and religious, liberal and conservative. A Catholic university is Catholic only insofar as its scholars, however diverse their frameworks and methods, maintain a serious engagement with the Catholic intellectual tradition. The central and animating question should be: What do the Catholic tradition and the many scholarly disciplines have to say to one another?

Notre Dame’s leaders endorse this ambition in many official statements. The university’s official mission statement is stark: “The University asks of all its scholars . . . a respect for the objectives of Notre Dame and a willingness to enter into the conversation that gives it life and character.” And: “There is [for faculty] . . . a special obligation and opportunity, specifically as a Catholic university, to pursue the religious dimensions of all human learning. Only thus can Catholic intellectual life in all disciplines be animated and fostered and a proper community of scholarly religious discourse be established.”

Former university president John Jenkins struck similar notes: “We must have a preponderance of Catholic faculty and scholars, those who have been spiritually formed in that tradition and who embrace it.” According to former provost Tom Burish, that “preponderance” entails “[having] a majority of faculty who are Catholic, who understand the nature of the religion, who can be living role models, who can talk with students about issues outside the classroom and can infuse values into what they do.” Former president Monk Malloy concurred: “It remains our goal that dedicated and committed Catholics predominate in number among the faculty.”

The central problem at Notre Dame is that these fine words are not acted upon in a remotely consistent and thoroughgoing manner. Various programs, centers, and institutes scattered across campus, and a certain number of individual faculty members, do work hard to engage the Catholic intellectual tradition. But at the institutional level, with the university as a whole, Notre Dame’s leaders are equivocal about that Catholic mission and make decisions and pursue practices that undermine it.

Compared to most other places, Notre Dame has many good things going on. But compared to what it could and should be—what it says it wants to be—Notre Dame is a disappointment. It’s not just that the university hasn’t reached its potential, it’s that it hasn’t seriously tried. Sustained engagement with the Catholic intellectual tradition happens in pockets, but leaders avoid the institutional efforts that would make this engagement consistent and integrated.

What might such efforts look like? To begin with, Notre Dame’s leaders should be consistently clear and vocal about the purposes and entailments of a university with a Catholic mission. Department chairs and deans should understand and support that mission by being intentional and careful in recruiting faculty who understand (or are willing to learn about) the mission of a Catholic university and can in good faith commit to supporting it in their own ways.

To this end, short-listed faculty prospects could be sent a friendly document explaining the Catholic mission and the many ways faculty can contribute to it. Interviews with faculty would include open conversations about the Catholic mission, not just about research and teaching records. New faculty hires might be given first-semester course releases for participating in a faculty seminar on the basics of the Catholic intellectual tradition and its place in Catholic higher education—not to indoctrinate, but to orient and inform. Reviews of tenure and promotion cases would include evaluations not only of faculty research, teaching, and service, but also of contributions to the Catholic mission.

In short, Notre Dame should advance its Catholic mission by means of standards and programs that involve truth-in-advertising, judicious hiring, incentives for faculty to learn about the Catholic intellectual tradition, and accountability for the expectation that faculty contribute to the Catholic mission. These are the kinds of initiatives institutions of all kinds implement—when they are serious about their missions.

Notre Dame can afford to implement these measures. But little in this vein is attempted. Many university leaders seem to have only a vague sense of what serious intellectual engagement with the Catholic tradition across academic departments might look like. Nebulous terms such as “identity” and “character” suffice. Though Notre Dame formally requires “a predominant number” of faculty to be Catholic, in many if not most cases that goal is achieved through a “tick the box” approach, whereby a candidate who was baptized Catholic but now despises Catholicism counts as Catholic. Faculty who have no business being at Notre Dame—both for the university’s mission and students and for their own sanity—are regularly hired and promoted with tenure.

No effort is made systematically to orient and educate new faculty in the Catholic intellectual tradition. Some department chairs are appointed who not only are indifferent to the Catholic mission but actively resist and subvert it. In my experience, talk of “mission hires” at departmental faculty meetings sometimes involves strategizing ways to recruit colleagues we want for reasons unrelated to Notre Dame’s Catholic mission, who might nevertheless pass “mission muster” in the dean’s office. Administrative tenure-and-promotion reviews scrutinize faculty research records but pay little attention to contributions to the Catholic mission.

Here is one anecdote, from a wealth of similar stories. A recent job candidate—a Catholic convert from Protestantism—emailed me this about her campus interview experience: “There were more than a few awkward moments when I was told some version of ‘and don’t worry about the Catholicism bit,’ to which my gut response was, ‘that’s the primary reason I applied,’ but which seemed like the wrong response.” Notre Dame has a knack for dispiriting just the kind of faculty it should most want on campus.

Notre Dame excels at being Catholic when it comes to liturgy, architecture, classroom crucifixes, ubiquitous chapels, campus artwork and statues, and (from what I have seen) residential life—that is, in atmosphere, aesthetics, and worship. Notre Dame also puts effort into honoring its Catholic commitments by “being a force for good in the world”—that is, by working to make the world a better place (although nearly every university claims to do that). I also think that the university’s human resources policies reflect a commitment to Catholic values. However, a university’s heart and soul are not found primarily in its atmosphere, humanitarian efforts, or HR policies, but in its intellectual life—its scholarship, teaching, and academic inquiry and formation. That life is what makes Notre Dame primarily an academic, not ecclesial or philanthropic, institution. Yet the intellectual life of the university is precisely where Notre Dame largely fails to be Catholic.

In my two decades of observation, I came to see that the strategy for serving the Catholic mission amounts to hiring tick-box faculty, requiring two theology and two philosophy courses for undergrads, recruiting the occasional Catholic “star” as a visible standout, and supporting certain interdisciplinary centers and institutes that take up the mission. Not bad. But not good enough, given Notre Dame’s stated aims. These efforts create pockets of mission-driven activities instead of integrating the Catholic mission across and within the core units of the university: academic departments. When it comes to the character of departments, university leaders take a mostly hands-off approach. And so we get “Don’t worry about the Catholicism bit.”

What explains the compromises and failures? At least three related factors play a role: fear of conflict, a craving for mainstream acceptance, and a desire to fast-track the process of becoming a pre-eminent research university.

Notre Dame’s leadership is petrified by the prospect of conflict. On every issue, dispute, or debate that might cause controversy, top administrators avoid institutional intervention like the plague. This is especially true when it comes to Catholic identity and mission. Notre Dame is a lightning rod for controversy in American Catholicism. Neither “trad” sectarian nor fully secularized, Notre Dame finds itself to be contested terrain in endless Catholic factional struggles (to which this essay now contributes). Pity the president. In his earliest addresses, John Jenkins laid out a truly impressive vision for Notre Dame’s distinctively Catholic place in higher education. He boldly asked, “If we are afraid to be different from the world, how can we make a difference in the world?” But there were missteps and blowups over The Vagina Monologues being performed on campus and President Obama being awarded an honorary degree. At times, the uproar on campus seemed like Berkeley in 1964. In my estimation, those conflicts induced a reaction of wary defensiveness.

That was one era, but the situation is endemic. Being a lightning rod locks university leadership into a pattern of conflict-avoidance. Rather than confidently advance the university’s stated Catholic mission—which would generate contention—Notre Dame’s leaders talk a good game and then retreat from the rough-and-tumble that implementing it would involve. Notre Dame’s marketing slogan, “What Would You Fight For?,” rings hollow when it comes to the stated central purpose of the university.

One example of the fear: In 2014, I (with John Cavadini) published a book titled Building Catholic Higher Education: Unofficial Reflections from the University of Notre Dame. It was in no way hostile, but as affirming and encouraging of Notre Dame as could be. Many outsiders read and discussed the book, contacting me with observations and questions. The entire faculty at one Protestant university on the West Coast struggling with its own Christian identity and mission read and discussed the book. I sent copies to academic leaders and many colleagues at Notre Dame.

The “response” was remarkable. A few colleagues in other departments said, “Nice work.” Not one leader of the university even acknowledged the book, much less asked to discuss it. Apparently, simply to see the topic addressed in print was frightening. The resounding silence was almost hilarious. I felt like the blunt son in a dysfunctional family who said a “wrong” thing at the dinner table and watched everyone freeze up and then carry on as if it had never been said.

Fear of conflict is debilitating to a university. Of its nature, academic life engages differing perspectives, names and forthrightly acknowledges disagreements, and works through arguments with civil critiques and replies. That is how disciplined inquiry gets anywhere. It is also what the Catholic Church and our entire American culture now desperately need to see modeled. Notre Dame’s Catholic mission should be a matter of ongoing questioning and argumentation. Different disciplines and programs may sort out its implications for their work. These necessary debates must recognize the centrality of the Catholic intellectual tradition, yet accommodate legitimate pluralism and sustain constructive conflict. Notre Dame’s fearful avoidance of conflict shuts all that down. What’s left are marketing slogans.

The second factor undermining the Catholic mission at Notre Dame is a craving for mainstream acceptance, especially by “peer” institutions: Duke, Northwestern, Vanderbilt, Washington University in St. Louis, Emory, Rice, Stanford, NYU, and the like. Notre Dame desperately wants to belong to this club. The anxious longing is odd. By many objective measures, the university already belongs. When it comes to endowment, campus facilities, admissions selectivity, alumni loyalty, sports programs, research, and many other standards of comparison, Notre Dame at least equals and often bests many of these peers.

Only one factor makes Notre Dame suspect: Catholicism. The Catholic thing is alien to Notre Dame’s peers. It’s okay for an individual within a university to be visibly Catholic, as was the case with Duke’s legendary basketball coach, Mike Krzyzewski, or the Crimson Tide’s Nick Saban. But an entire institution claiming to be seriously Catholic? That is suspiciously medieval, perhaps dangerously authoritarian. Thus, the very Catholicism that constitutes Notre Dame’s institutional identity also threatens its embrace by peer research universities. The “Catholic bit” is an embarrassment.

Everyone needs social acceptance, but the need seems especially powerful at Notre Dame, in ways I never sensed while serving on the faculties of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Gordon College. My best psychosociological interpretation: It derives, at least in part, from the long historical experience of American Catholicism.

Notre Dame belongs to a tradition that was long excluded and persecuted. The Protestant and secular mainstreams viewed Catholics as dirty, working-class, urban ghetto immigrants who were probably more loyal to the pope than to the nation. The history of exclusion, harassment, and discrimination was horrid. In the 1920s, Notre Dame students physically brawled with the Ku Klux Klan in the streets of South Bend just to defend American Catholics’ right to exist. Notre Dame’s slogan, “God, Country, Notre Dame,” expresses a desperation to be believed loyal to the nation. Notre Dame’s ultra-patriotic ROTC program reflects the same desire.

John F. Kennedy’s election as president in 1960 indicated that American Catholics might be regarded as trustworthy Americans. And though American Catholics have since enjoyed a dramatic rise in socioeconomic and political status, Catholic teachings on abortion, birth control, same-sex relationships, the male priesthood, and other culture-war issues embarrass many Catholic professionals and intellectuals. The clerical abuse scandal and cover-ups by bishops were rightly excruciating. The history of Catholicism in America and the firmness of the Church’s positions on morally and culturally sensitive issues puts pressure on Notre Dame to adopt a version of Catholic higher education that won’t cause its representatives to be snubbed at the bar and on the golf course.

University leaders are not wrong to worry that serious faculty engagement with the Catholic intellectual tradition could get Notre Dame’s just-acquired Association of American Universities membership card revoked. The practices I suggest above could be viewed as oppressive impositions on academic freedom and scientific inquiry. Many Notre Dame faculty are embarrassed by the perception that the university’s Catholic commitments might impinge on their scholarship. What will the editors of top journals say? Far better to conform to mainstream norms and downplay the Catholic bit as a legacy to be finessed.

This dynamic shaped my own department. A few decades ago we might have paused and reassessed the purposes and practices of our entire discipline, re-envisioning what sociology might look like at its best, refracted in part through the Catholic intellectual tradition, especially Catholic Social Teachings. We might have had the courage to do something truly different—as I tried to do in some of my work on personalist social theory—and might have leavened the entire discipline of sociology over the long run.

Instead, we have mimicked every other sociology department, trying to claw our way up the rankings. The highest priority coming from the dean’s office was that our faculty should publish in top journals. Catholicism’s influence was quarantined in certain fields of interest: religion, family, and education. (Even this reductive understanding of mission, as counting studies on “Catholic topics,” has been partly abandoned.) In the end, we neither fulfilled Notre Dame’s Catholic mission nor became a great sociology program.

A crazy irony is at work: Notre Dame is chasing the acceptance of peer institutions that are far more lost than Notre Dame when it comes to the parameters and final purposes of higher education. Notre Dame allows its mainstream peers to set the terms—however confused and misguided—and then conforms to them. The fact that it does this should be the true source of its embarrassment. Notre Dame could forge a new university model, one that might foster a renewal of American higher education. (“If we are afraid to be different from the world, how can we make a difference in the world?”) Notre Dame is the one Catholic university in the world with the financial and alumni resources to pull it off. But doing so would require clarity of vision and strength of courage, and these I have not seen.

A third and related explanation for Notre Dame’s failure to fulfill its Catholic mission is its ambition to become a globally pre-eminent research university. Not long before my arrival, the Board of Trustees and campus leadership apparently decided that the university would no longer be content to pursue excellence in undergraduate liberal arts education, with a side serving of graduate studies, and maintain a serious Catholic identity. To those two goals a third was added: becoming a great research university—not cautiously, but as expeditiously as possible.

I was recruited to Notre Dame in part to help achieve that goal. And Notre Dame has undeniably made advances on this front. The problem is not the aspiration itself. The problem is the unrealistic belief that this third goal could be achieved without cost to at least one of the other two.

People in business and project management recognize a concept known as the “Iron Triangle” or “Triple Constraint.” In any production process, one can achieve only two of three desired features—cheap, fast, and high quality—but never all three. Cheap and fast is doable, but at a cost to quality. Fast and high quality is possible, but it will be expensive. And cheap and high quality can be done, but never quickly.

Notre Dame’s threefold ambition—maintaining excellent undergraduate education, sustaining a strong Catholic mission, and rapidly becoming a great research university—is an attempt to overcome the constraints of the Iron Triangle. Notre Dame admits that its project is “ambitious.” It should rather admit that it is impossible.

Here is how things are working out: The first goal (excellent undergraduate education) continues to be realized well enough; the third goal (a great research university, fast) has enjoyed significant but unspectacular progress; and the second goal (Catholic mission) is compromised. The latter outcome is not the result of failed execution. It is the predictable result of an inexorable logic.

Why can’t the fast-and-high-quality-but-expensive option work? In the current environment, no amount of money can generate enough believing Catholic scholars who are also top-shelf researchers and excellent teachers. It would take massive investments across many decades to produce anything like a pipeline of such scholars. What is available today? Scholars who can advance Notre Dame’s research agenda, yes, but many of them are neutral-to-hostile toward Catholicism.

Furthermore, to ask new faculty to spend time, energy, and attention on the Catholic intellectual tradition would—even if they were amenable—distract them from the very research activities that Notre Dame hired them to perform. As Notre Dame faculty engage with the Catholic intellectual tradition, their peers elsewhere work with total focus on scholarly productivity. Notre Dame faculty cannot be asked both to compete with their peers as scholars and to take on the extra learning and discussions that a robust Catholic mission requires.

In short, the imperatives of Catholic mission are impediments to the success of a modern research university. Understanding how the Catholic intellectual tradition interacts with mainstream academic disciplines is a burden that only a few, some of them at Notre Dame, readily shoulder, prepared for some career costs, out of love for an integrated life of the mind. For Notre Dame to imagine that it can, in a short time frame, populate its faculty with a predominance of atypical characters of this sort is delusional.

The governing logic of the modern research university is hyper-specialization. A Catholic mission that focuses on intellectual life (not just humanitarianism) tends in the opposite direction: toward integration, holism, coherence of thought and life. Notre Dame credulously thinks it can have its hyper-specialization and its integration, too. This refusal to recognize hard limits and trade-offs leads to the inevitable compromise of the Catholic mission. (Over time, given the governing priorities of nearly every research university, it will take herculean efforts to prevent Notre Dame’s mission of excellence in undergraduate education from being sacrificed, as well. It has happened everywhere else, for obvious reasons.)

I want to be clear on a crucial point: None of my analysis privileges Catholic conservatives over liberals, or even religious people over secularists. I’m concerned about the integrity of a distinctive institution, not positions on a political or theological spectrum. Very different faculty—including atheist and religious faculty who are not Catholic, and both liberals and conservatives—may contribute to Notre Dame’s Catholic mission in valuable ways. (However, the claim that “I support the Catholic mission by believing in peace and justice” grows old. What academic champions war and injustice?) An atheist with the right knowledge, intentions, and methods can support Notre Dame’s Catholic mission better than a disgruntled Catholic or indifferent careerist.

I will go further. Conservative activists who mobilize pressure campaigns against what they see as Notre Dame’s apostacies can do more harm than good. Their tone, and sometimes their methods, reinforce the conflict-aversion that shuts down constructive discussions of Catholic mission. Worse, their pet issues misleadingly imply that Catholic university faithfulness can be reduced to a set of positions in the culture war. The most fundamental issue at stake is not gays or abortion, but serious engagement with the Catholic intellectual tradition in academic work.

Relatedly, my criticisms here concern the gap between Notre Dame’s clear and repeated statements of purpose and the reality I have observed over two decades—not the notion that Notre Dame has fallen away from some “golden age” of faithfulness. Mine is not a story of historical decline—which I do not have the perspective to assess—but a reality check on stated goals.

Furthermore, the theologically orthodox are not always the “good guys.” For some time, with the support of my dean, I made efforts to encourage my friends in the department of theology to leave their disciplinary cocoons and interact intellectually with colleagues in other departments. I wrote and circulated a paper about how Pope John Paul II’s Ex Corde Ecclesiae (1990) obliges theology faculty at faithful Catholic universities to engage colleagues in all disciplines. This initiative culminated in a meeting with most of the Notre Dame theology faculty, whose fundamental posture, I was astonished to find, was a willfully suspicious, self-protective isolationism. Today, we don’t know what conversations about the implications of Catholic beliefs for psychology or physics or film studies (and vice versa) might look like, in part because most of Notre Dame’s theology faculty stay in their disciplinary shell. Blame for failures to live up to Notre Dame’s Catholic mission lies with many parties.

Not all of the problems that drove me away from Notre Dame obviously pertain to Catholic mission. Another is Notre Dame’s out-of-control branding, marketing, public relations, social media, fashion line, entertainment, and merchandizing machine. That juggernaut has grown so powerful that Notre Dame, Inc., increasingly operates in a world of curated appearances with little connection to academia or Catholicism.

Exhibit A: the campus “bookstore.” When I first arrived, the entire main section of its ground floor was occupied by shelves of books, including serious academic, theological, and devotional works. For years now, that space has been given over to an ocean of Notre Dame clothing and other branded merch and bling. Want a book? Head to a corner upstairs. The attached coffee shop, which once afforded modest comforts for conversation, has changed into a barren self-serve grab-and-go. Browsing Notre Dame’s online store a few years ago, I stumbled on tarot cards and other occult paraphernalia. This is not surprising, as Notre Dame has outsourced responsibility for key campus centers to clueless marketing consultants and contractors. So now we have an Irish-inflected Macy’s–Martha Stewart–Apple Store emporium. This is not subtle mission drift, but blatant surrender to profit-maximizing consumerism.

There are other schemes: star-studded stadium concerts (AC/DC, Billy Joel, Garth Brooks), weekend football trips to Ireland, the inanely marketed “Notre Dame Family Wines,” and more. Notre Dame alumni, parents, and “friends” have become a lucrative consumer base to milk. I want to ask: Who is in charge here? Who gave whom permission to turn Notre Dame into a self-aggrandizing entertainment and shopping carnival? How does this project reflect Catholic purposes or values? Why does nobody see what is going on, and the message it sends to students who are already drowning in digital noise and commercial gluttony? St. Augustine wrote that the world is ruled by libido dominandi. To the very same, it seems to me, Notre Dame is far too captive.

I love the motto of my former state of North Carolina: Esse Quam Videri, “To be rather than to seem.” Notre Dame’s public image and marketing machine promotes the opposite imperative, “To seem rather than to be.” Why work with educated integrity on environmental stewardship, for instance, when it’s easier to develop a shiny “green” digital advertising image? The “Notre Dame family” appears happy to be duped by its own marketing. I couldn’t take it anymore.

And then there was my own intellectual life. I realized I was starving at Notre Dame, enjoying only one rewarding interlocutor from another department. On the surface, the university seems awash in intellectual activity. Bulletin boards are layered with posters advertising talks by speakers. Graduate student training workshops meet weekly to discuss articles and papers in progress. Seasonal cycles of faculty recruitment fill schedules with sometimes interesting job talks. But this adds up to a scratch-and-sniff intellectual life—not colleagues and students engaged in ongoing, serious conversations and arguments about big ideas, assumptions, theories, methods, and research programs.

Why the lack of intellectual life? Partly for me it was the result of American sociology’s mostly ceasing to engage the big-picture questions that drew me into the discipline in the first place. Beyond that, faculty are too harried—by careerist competition and bureaucratic demands—to sit down and talk ideas. At most universities these days (and certainly at Notre Dame), we are busy attending administrative meetings, writing annual reports, collecting neoliberal efficiency metrics, assimilating procedural updates from administrative staff, discussing program revisions, attending candidate talks, gathering external review letters to assess colleagues, and meeting endless other bureaucratic and resume-building demands, so that we have little time and energy to think and talk of things intellectual. Notre Dame’s fear of conflict likewise discourages faculty and students from discussions that would lay bare disagreements.

Notre Dame graduate students have for some years been pressured to complete their doctorates “efficiently” under threat of losing their funding (even as the university’s budget generously affords the hiring of new armies of non-academic administrative staff). This misguided policy puts grad students on the specialization treadmill, making it far less likely that they will read, think, and talk about the ideas that matter most. We are pushing out technicians with doctorates, not properly formed intellectuals.

Sociologists call this phenomenon “goal displacement”: Time and energy are increasingly consumed by secondary organizational processes, which supplant what should be primary. In a university context, the work of administrative upkeep, “career advancement,” and university status becomes dominant, and the work of thinking, reading, talking, collaborating, and learning about important ideas recedes in importance. Goal displacement is happening at every university. But it is acute at Notre Dame—and deleterious to its Catholic mission.

Former president Ted Hesburgh used to say (with some self-congratulation, I always thought) that Notre Dame is “the place where the Church does its thinking.” These days, few have the time or energy to think much at all, whether on the Church’s behalf or otherwise.

Academics love ideas. They love exploring, understanding, explaining, and sharing research with colleagues, students, and readers. This love drives aspiring professors to endure graduate school for long years after college, and to work nights, weekends, and vacations for the rest of their careers. Faculty are of course willing to do administrative work in order to keep their institutions running. But when intellectual life is crowded out by career stressors and bureaucratic takeover, the professor’s soul slowly dies.

I could say more about why I left Notre Dame. There was the disconnect between the environmental-sustainability programs taught in classrooms and the “hidden curriculum” of self-indulgent, ecologically destructive attitudes and practices, evident in wasted energy, plastics, and food on campus—a glaring hypocrisy against which I struggled with operations staff for years to ameliorate, totally in vain.

There was the bright senior finance major (a committed Catholic weeks away from graduating and anxious about environmental problems) who told me, after we discussed Catholic Social Teaching on creation stewardship in my environmental sociology class, that she had never heard of Catholic Social Teaching during her four years in the Mendoza College of Business. This was a mind-blowing dereliction of duty: sending wonderful students out to “Grow the Good in Business™” without trained knowledge of Catholic teaching on socioeconomic life.

There were the multiple gut punches of sometimes inept, sometimes underhanded decisions and dealings by various administrative authorities in the Main Building. There was the dark side of Notre Dame’s dyed-in-the-wool, bleeding-blue-and-gold, insider family loyalty, beset by a subtle parochialism yet also subtly exacting an almost mafia-like allegiance, alert to any disaffection and averse to any self-criticism.

There was the experience of being thrown under the bus by a former department chair who preferred to coddle a faction of woke graduate students seeking to overthrow our discipline’s theory canon rather than stand behind a colleague, whose offense was to ask those students to answer hard questions about their ideas. My colleagues froze with fear when a junior colleague endorsed the charge of one of the graduate students that our entire university and sociology department were “white supremacist.” Nothing petrifies white liberals more than the imputation of being “racists.”

I know these problems can afflict any organization. But Notre Dame does not sell itself as just any organization.

Much of this is on me. I have never done well with institutions whose performances fall far short of their stated principles. It’s probably some residue of Protestant Reformation sensibilities in me. I also have difficulty not naming things frankly what they are. That’s my Philadelphia upbringing, no doubt. I own it. But at some point the personal costs became intolerable.

Whether Notre Dame realizes or squanders its opportunity to become a genuinely Catholic university—that is on Notre Dame. I am certain that the last thing the world needs is yet another pretty-good-but-not-great research university, “Catholic” or otherwise. I am putting my lost battles behind me. For those who still care about Notre Dame, perhaps this postmortem will be of value. But I advise: Don’t get your hopes up.

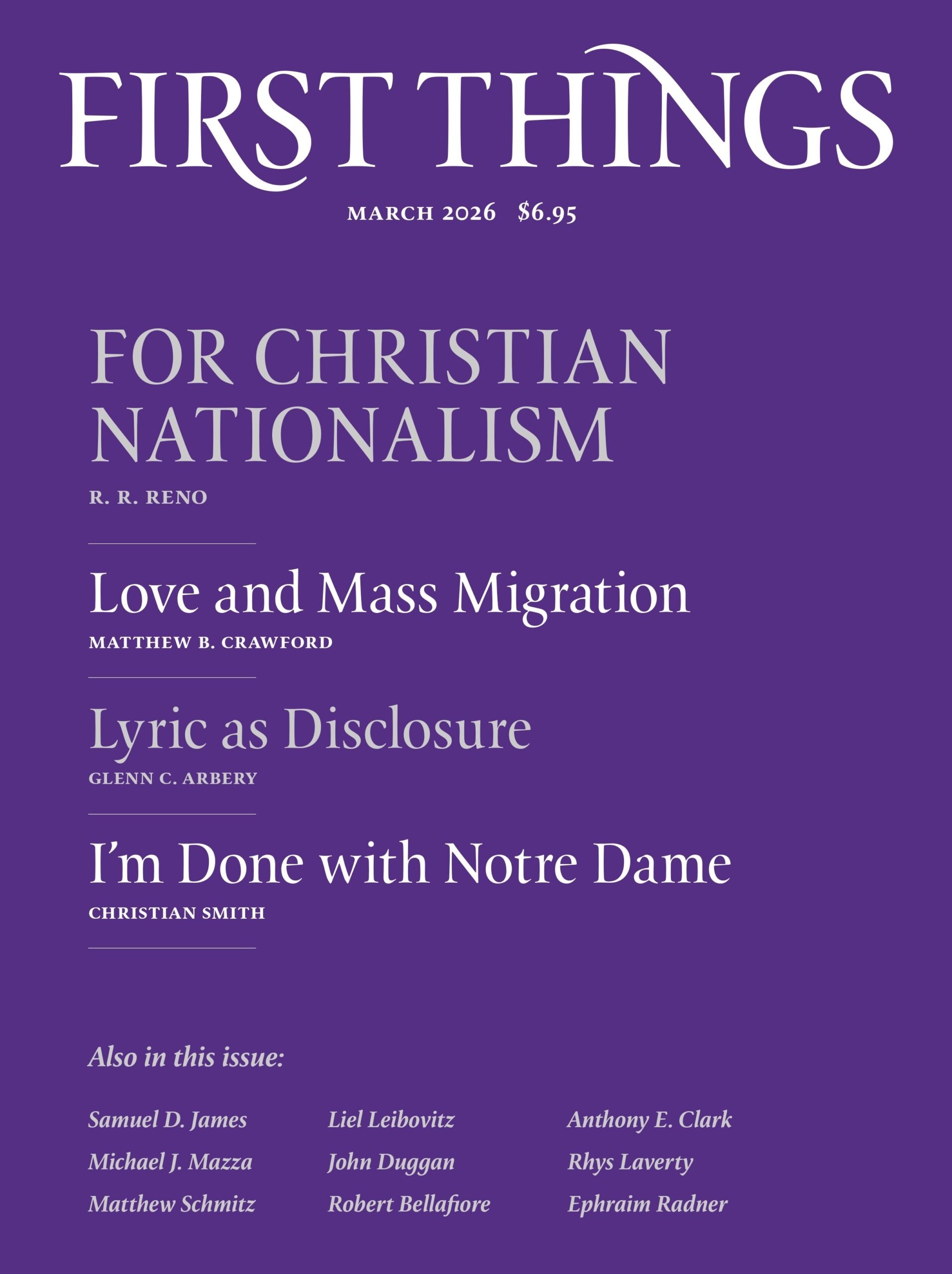

Image by Dan Dzurisin, licensed by Creative Commons. Image cropped

Students for Notre Dame

As I walked out of class Thursday morning, the day before the planned student-led “March on the…

What the USCCB Gets Wrong About Birthright Citizenship

In the wake of the 2007 Supreme Court decision to uphold Kansas’s ban on partial birth abortion,…

Politics of the Professoriate (ft. John Tomasi)

In the latest installment of the ongoing interview series with contributing editor Mark Bauerlein, John Tomasi joins…