It was Gerstäcker’s mother. She held out her trembling hand to K. and had him sit down beside her, she spoke with great difficulty. It was difficult to understand her, but what she said”—thus ends Franz Kafka’s final novel, The Castle. If he intended to finish the novel (a point of debate among Kafka aficionados), then death intervened to ensure that the work literally ended mid-sentence.

The ending of The Castle captures the impact of human mortality. Accidental though it may be, its sheer incoherence makes it a stroke of genius in its presentation of the human condition. I have faced the very real and unexpected prospect of imminent death twice. The first was a few years ago when I suddenly found myself facing the business end of a pistol held by a rather angry and unstable fellow who had stepped out of the shadows to confront me. He then spent fifteen minutes telling me he was going to pull the trigger and terminate my existence. The second was more recent, when I was afflicted with an unforeseen and catastrophic medical incident. Like many, I had always wondered what my feelings in such circumstances would be. Strange to tell, on neither occasion did I feel much panic, perhaps because everything was happening so quickly. Rather, my dominant emotion was melancholy confusion, summarized in the sentence, “What an absurd way for it all to end!” My life, as I saw it both times, had not yet reached its logically coherent and satisfying conclusion. I was going to depart this life too soon.

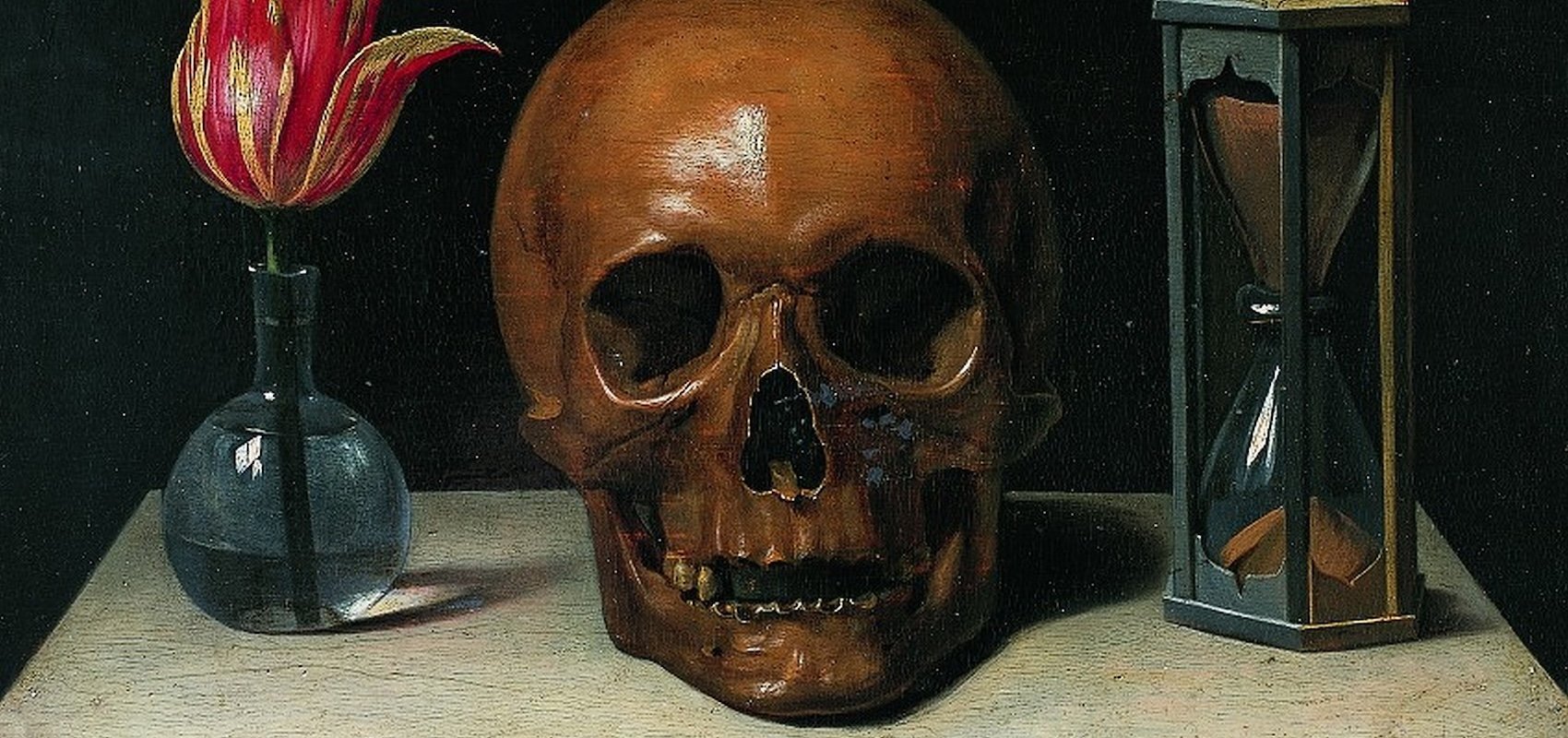

Perhaps it is the fact that we live in a culture that has pushed death to the margins that makes us resent not just its inevitability but also its absurdity. We no longer have the regular, even routine, exposure to it that our ancestors did. I have never been present at a death. Few in the younger generation have even seen a dead body. Death occurs in faraway places and to other people. We don’t need categories for handling it, and so when it intrudes upon our worlds, we don’t know how to respond.

Perhaps more significantly, a world saturated with movies and TV shows trains us to think that life must have a plotline and a structure. It must have a beginning, a middle, and an end. These must stand in continuity with each other and make sense as a whole. But in reality, this is not so. Life just ends. Indeed, as with Kafka’s novel, it ends mid-sentence, with business permanently unfinished. There are still words to be spoken, things to be done, conversations to be had, friendships to be enjoyed, kisses to be given and received. But there is no satisfying, coherent resolution to the whole.

That is where the Christmas story comes into play. Death is the enemy that makes all of life ultimately absurd, and the Incarnation is the beginning of the answer, the start of that which brings a coherence to creation. Light shines in darkness and the darkness has not overcome it. If life for me, as for all of us, ends mid-sentence, then that is where grace begins. Yes, there is continuity in the gospel. The New Testament’s genealogies and attention to Old Testament prophecy testify to the historical continuity of the Messiah’s mission but this does not overwhelm the fact that Christ represents a decisive break in the ages. Light explodes into the bleak, dark night of human existence, contradicting it and putting it to flight, just as the cross will later contradict all human moral and epistemological expectations of how God should act. How many of us will receive cards this Christmas showing the child in the manger as the source of light for Mary, Joseph, and the other witnesses to his birth? There is a serious theological truth being represented there.

Of course, in an obvious play on those scenes, later artists presented science as the source of light. But we live at a time when science is much more morally ambiguous and where attempts to make sense of life by claiming that the darkness is light have run their course. Reality is beginning to dawn for many. Even many intellectuals are now taking the Christian message seriously, at least as something to be considered. There are, of course, those who think that light is a good idea, even though they do not believe it really exists. Even Richard Dawkins has grudgingly gestured toward “cultural Christianity” in a desperate attempt to set limits to a science unencumbered by any sense of final causality.

But that will not do. One cannot reduce Christianity to a matter of merely instrumental importance. Like those TV shows and movies that present life as having a beginning, a middle, and an end, such approaches are insufficient, a form of nihilism that wants the benefits of the faith while denying those truths upon which those benefits necessarily rest. The Christmas message makes claims about life and about God, not least that life makes no ultimate sense without God, doomed as it is to end mid-sentence for all of us. And only in the child lying in the manger do we see how those sentences can be completed.

Announcing Portico: A New Literary Quarterly

First Things is pleased to announce the publication of its new print literary quarterly, Portico, starting in…

Antoni Gaudí’s Icon of the Universe

This year marks the hundredth anniversary of the death of Antoni Gaudí, the great medievalist-modernist architect from…

Uncovering the Christian Past: New and Notable Books

Several books on some aspect of the history of Christianity have recently come my way. “The Most…