Two decades ago, I was an undergraduate at McGill University, where Charles Taylor lectured. Taylor, born in Quebec in 1931, is one of the most important philosophers of modernity and a public Catholic intellectual. His great theme has been the shift from a world where belief was taken for granted to a world where faith is one option among many. He tells the story of how we moved from Christendom to the “secular age,” when unbelief became not only possible but plausible. For students like me, he was magnetic. He explained the cross-pressures of our time—the longing for faith and the ease of doubt—without scorn. Taylor dignified fragility. He showed us why belief feels tenuous and, in doing so, gave us recognition. I, like many others, was enchanted.

At the same time, I was reading Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik. Known simply as “the Rav,” Soloveitchik (1903–1993) was heir to a rabbinic dynasty, trained in both Berlin philosophy and the Lithuanian yeshiva world, and for decades the head of Yeshiva University’s rabbinical seminary. He shaped American Orthodoxy with a mind both rigorous and pastoral, insisting that covenant could survive in modernity but not without cost. In The Lonely Man of Faith, he describes two Adams: the first a majestic cultural builder, the second a covenantal man bowed in submission before God. Modern culture exalts the first and isolates the second, leaving the man of faith to pay “the price of heroic loneliness.” At first I thought Taylor and Soloveitchik belonged together: Taylor gave a philosophy of fragility, the Rav gave a theology of loneliness. Both dignified the modern believer’s condition.

But enchantment and truth are not the same. Taylor’s genius is to describe the atmosphere of modern life. His danger is to treat that description as destiny. Fragility becomes not a wound to be healed but a climate to be endured. In A Secular Age he writes that we live in a condition where there are many construals of the world, and “these are not mere errors.” His generosity toward pluralism makes him humane, but it leaves us paralyzed before the question of truth.

His most famous diagnosis, the “Age of Authenticity,” makes the point. We moderns believe each of us has a unique way of being human, and our highest good is to be true to ourselves. That sounds noble, and it resists conformity. But it also makes truth subservient to self. Taylor admits that the dark side of individualism is a narrowing into the self, but he leaves it there, as malaise rather than rebellion. Fragility, in his hands, is no longer something to resist but something to accept.

Soloveitchik refuses this confusion. Loneliness is not fragility. It is the cost of covenant. Adam the second is not fragile; he is bound. The Rav’s halakhic consciousness insists that God’s will is objective, not subject to consensus or feeling. He warned that when halakhah is reduced to symbol or metaphor, its categorical claim is lost. It no longer commands; it merely suggests. Where Taylor dignifies fragility, Soloveitchik insists on law.

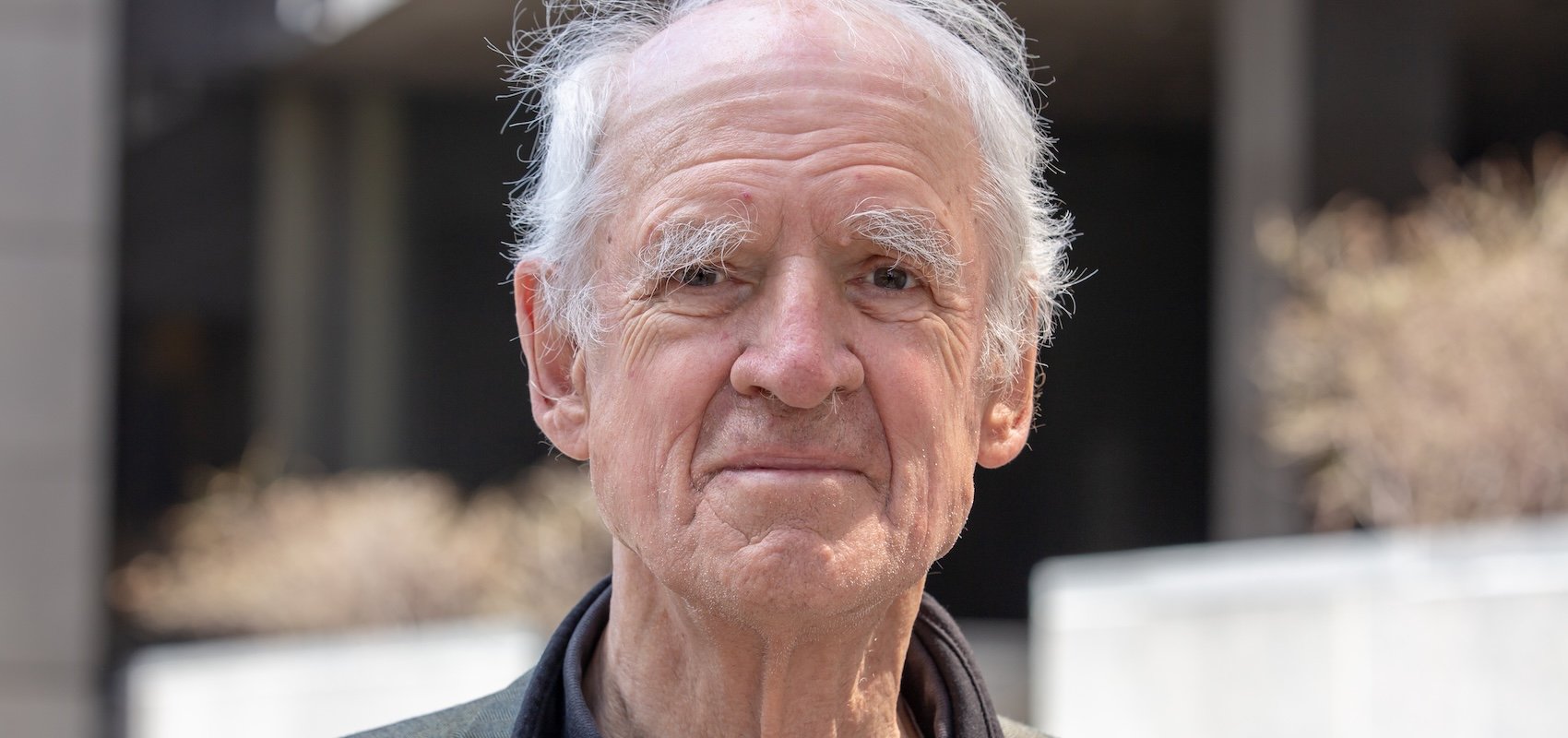

Joseph Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, pressed the same point with Catholic precision. Born in Bavaria in 1927 and marked by the devastation of war, Ratzinger rose from the lecture halls of Germany to the Second Vatican Council, to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and finally to the papacy. He was often caricatured as severe, but in truth he was one of the great Catholic theologians of the century, combining pastoral concern with intellectual clarity. His lifelong question was how faith can endure in a culture that treats truth as negotiable.

Ratzinger diagnosed with unflinching clarity what Taylor only described. Where Taylor saw pluralism as dignity, Ratzinger warned of the “dictatorship of relativism.” Where Taylor accepted fragility as a condition, Ratzinger saw it as captivity. In Introduction to Christianity he wrote that the question of God is the question of truth—not lifestyle, not preference, but truth.

Nowhere was this clearer than in liturgy. Taylor’s “Age of Authenticity” tempts us to see worship as one more space for self-expression. Ratzinger rejected that outright: Liturgy is not about what pleases us, not a cry into the dark of our own creativity. It is God’s action among us, our entry into the great worship of the communion of saints. Soloveitchik struck the same note from a Jewish angle: Prayer is not the outpouring of subjective experience but the service of God, rooted in covenant and disciplined by halakhah. Taylor describes why worship feels fragile; Soloveitchik and Ratzinger insist fragility is not fidelity.

The same holds for relativism. Taylor tells us we must live with many construals, none of them mere errors. Soloveitchik called that posture subjectivism; Ratzinger called it tyranny. Both refused to let pluralism pass for humility. And both saw that once truth is surrendered to preference, tradition collapses. For Ratzinger that meant liturgy remade by taste; for Soloveitchik it meant halakhah reduced to symbol. In both cases, the sacred loses its authority and becomes a mirror of the self.

Ratzinger’s pastoral eye saw that these were not abstractions. They eroded the most basic practices of faith. In education, he warned, relativism turns formation into indoctrination in the fashions of the moment. In worship, it turns liturgy into performance. He understood that a faith offered as one option among many will not endure, because no one will suffer for a lifestyle choice. Only truth is strong enough to carry generations.

And here is the lesson for Jews as well. Our schools face the same temptation to present Judaism as heritage rather than covenant. When day schools make formation into self-expression, they produce consumers of identity, not disciples of Torah. Our synagogues face the same temptation to market worship as “authentic” because it feels relevant, tailored to attention spans and moods. But prayer is commanded before it is chosen. It binds before it pleases.

Taylor helps us name the condition of fragility. Soloveitchik makes us feel the loneliness of covenant. Ratzinger insists on truth as the only ground that can sustain worship and education. Together they reveal the challenge of modern faith—but only Soloveitchik and Ratzinger point us beyond description to fidelity. If Jews are to endure as a people of faith, we cannot be content to describe fragility. We must teach truth, pray truth, and live truth. Only then will our children inherit not a fragile option but a living covenant.

Image by Lëa-Kim Châteauneuf, licensed via Creative Commons. Image Cropped.

Against “God Alone”

A few years ago, I had some routine surgery. Something went wrong in recovery. The nurses on the…

The Scandal of Judaism

Christianity has been marked by hostility toward Jews. I won’t rehearse the history. I’ll simply propose a…

Trump’s Civilizational Project

Secretary of State Marco Rubio spoke at the recent Munich Security Conference. Last year, Vice President JD…