People can get used to most anything. Even the abyss may be rendered tolerable—or, for that matter, luxurious—furnished with creature comforts so that the unbearable truth of one’s condition is overlooked: a pair of lavishly upholstered armchairs, some choice pictures on the wall, bookcases laden with the best that has been thought and said, a sound system worthy of your favorite Beethoven and Brahms recordings, a well-stocked liquor cabinet, soothing overhead track lighting, and strategically placed table lamps to make you almost forget the perpetual darkness outside your walls. The hell with the world outside, anyway: You’re home, the best place there is, you’re prosperous and well liked, you’re a fine example to your children, your wife and your mistress are better-looking than you deserve, and you can’t imagine a better life than the one you’ve got.

“The specific character of despair is precisely this: it is unaware of being despair.” So declares Søren Kierkegaard in The Sickness Unto Death, and the novelist and essayist Walker Percy (1916–1990) uses this quotation as the epigraph to his first novel, The Moviegoer (1961), which won the National Book Award, remains his most celebrated work, and heads the new Library of America edition of his early writings. Binx Bolling is the hero of this novel, and he tells his own story: Pushing thirty, a stock and bond broker in his uncle’s firm, living in a basement apartment in the nondescript New Orleans suburb of Gentilly, Binx at first seems a paragon of the dullest conformity, a surefire candidate for unwitting despair. “I am a model tenant and a model citizen and take pleasure in doing all that is expected of me.” Watching television and going to the movies are the activities that occupy most of his evenings. The local movie house advertises itself as the haven “Where Happiness Costs So Little. The fact is I am quite happy in a movie, even a bad movie.” Whereas other people cherish memories of moments of high excitement from their own lives, Binx remembers John Wayne’s gunslinger heroics and Orson Welles’s glamorous villainy. One fetching young woman or another often accompanies him to the pictures, for he falls in love, or something like it, early and often, and makes a habit of bedding his secretaries. These momentary sweethearts leave his employ when the loving dries up. “No, they were not conquests. For in the end my Lindas and I were so sick of each other that we were delighted to say good-by.”

In the hands of a novelist of more punitive temperament, a John Cheever or a John Updike or a Philip Roth, a man like Binx might be doomed to inconsequence and middle-aged defeat before his time. But Percy’s hero possesses a saving longing for a life worth living. This singular man appreciates that his daily round ought to be a perpetual renewal of “the wonder,” and he dedicates himself to the search for a worthy source of this most precious treasure. He hesitates to say that he is seeking God, for the opinion polls tell him that 98 percent of his countrymen already call themselves believers, with the remnant professed atheists or agnostics, and there is scant distinction in being “dead last among one hundred and eighty million Americans.” As he thinks things over, whether he is a laggard or a pathbreaker in his seeking is unclear to him. “Have 98% of Americans already found what I seek or are they so sunk in everydayness that not even the possibility of a search has occurred to them?”

Rescue, or at least respite, from everydayness—Martin Heidegger’s coinage, a mouthful in German, Alltäglichkeit, denoting routine and inauthentic existence—comes from the intrusion of death upon carefully modulated, well-lighted lives. For Binx, it was lying wounded by Chinese gunfire in a ditch in Korea that made him feel most alive and prompted his vow to search for the wonder. For Kate Cutrer, Binx’s stepcousin, the revelatory near-miss was surviving a car accident that killed her fiancé. As she says to Binx,

Have you noticed that only in time of illness or disaster or death are people real? I remember at the time of the wreck—people were so kind and helpful and solid. Everyone pretended that our lives until that moment had been every bit as real as the moment itself and that the future must be real too, when the truth was that our reality had been purchased only by Lyell’s death.

The unreality of her pedestrian, psychiatrically monitored days and nights weighs her down, and after walking away from psychotherapy and entertaining with amused skepticism a marriage proposal from Binx that is the most feckless ever recorded, she takes an overdose of Nembutal. She doesn’t die, and she claims she knew the dose would not be enough to kill her. She just needed a break—to slide a bit “off-center.” “Everything seemed so—no ’count somehow, you know?” The family elders aren’t buying it, and they react with consternation to what they consider a suicide attempt in earnest.

Soon afterward, Binx takes Kate along on a business trip to Chicago, and they don’t let the family know she is going with him. Despite a botched attempt at making love, the two of them begin to realize that they belong together and might even be each other’s salvation. When they return, Binx’s outraged Aunt Emily, Kate’s stepmother, lets him have a blast of her contempt right in the face with both barrels. Her personal disgust swells into an eloquent diatribe against the rotted all-American character: “Ours is the only civilization in history which has enshrined mediocrity as its national ideal. . . . What is new is that in our time liars and thieves and whores and adulterers wish to be congratulated and are congratulated by the great public, if their confession is sufficiently psychological or strikes a sufficiently heartfelt and authentic note of sincerity.” Hers is the very best worldly wisdom: stoic, aristocratic, disdainful of gross moral collapse that nowadays passes for acceptable behavior. Mournfully she invokes the times they listened to music, read the Crito together, and spoke of “goodness and truth and beauty and nobility.” But Binx says he doesn’t love these things or live by them, and when she presses him on what he does love and live by, he is silent. There is little doubt that Percy, in some vital part of his soul, exults in Emily’s hottest animadversions, and certain readers have thought this harangue the author’s last word on Binx’s spiritual condition. Yet it also seems apparent that Emily is unable to see clearly into a soul as murky as Binx’s and discern the light that shines there, however dimly.

For when, by and by, Binx is moved to reflect on the state of the world and his place in it, he sounds not unlike Aunt Emily, though far less polite:

My only talent—smelling merde from every corner, living in fact in the very century of merde, the great shithouse of scientific humanism where needs are satisfied, everyone becomes an anyone, a warm and creative person, and prospers like a dung beetle, and one hundred percent of people are humanists and ninety-eight percent believe in God, and men are dead, dead, dead; and the malaise has settled like a fall-out and what people really fear is not that the bomb will fall but that the bomb will not fall—on this my thirtieth birthday, I know nothing and there is nothing to do but fall prey to desire.

To reach for the nearest warm girl—as long as she’s not Kate—is once again his reflex. But Kate is somehow the one for him, and riding a tidal wave of decisiveness and personal responsibility, he not only marries her but also honors Aunt Emily’s wish that he go to medical school.

What exactly got into our boy, and what can come of this sudden resolve to change his life? Percy’s philosophical learning undergirds his hero’s transformation, as Binx shows himself a practicing existentialist along the lines laid down by Kierkegaard. The quest for the wonder, the everlasting core of truth and light, Binx sets aside. As “the great Danish philosopher” has written, Kierkegaard himself lacked the authority to proclaim the truth but at best could only edify, and a blighted century later, Binx is in no position to do even that—“or do much of anything except plant a foot in the right place as the opportunity presents itself—if indeed asskicking is properly distinguished from edification.” Practical wisdom now guides his way. Like William James escaping the doldrums of fatalism, his first act of free will having been to believe in free will, Binx’s decisiveness proves above all that the course of his life is his to decide. The past need not bind him, nor incalculable possible futures confuse him. The romance of limitless possibility that marks Kierkegaard’s aesthetic man, Mozart’s hell-bent Don Giovanni being the exemplar, contracts to the settled intention of the ethical type, the one who loves his wife alone and wills the life that comes with such exclusivity.

Binx admits that he does not have it in him to become the type of man whom Kierkegaard considered the highest: the religious. The very word religion strikes Binx as suspect. Yet when his fourteen-year-old half-brother dies, Binx consoles the remaining children with calm certainty about the life eternal: When Our Lord raises us up on the last day, Lonnie won’t need his wheelchair, but will be like the rest of us—able not only to walk but to go skiing. Percy confirmed the insight of perceptive commentators that he had in mind here the final scene of The Brothers Karamazov, in which Alyosha assures a group of neighborhood boys that they will always remember their friend Ilyushechka, who has just died, and that at the appointed hour they will all rise from the dead, meet one another again, and tell joyously of everything that has been. The comparison with the saintly Alyosha attests to what is extraordinary in Binx’s soul. You can’t tell whether he will live up to it or retreat into everydayness, but at novel’s end you are pulling for him.

The sentiment of the Kierkegaard epigraph can stand as the motto for Percy’s entire oeuvre, much as the memorable lament “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation” commonly does for Thoreau’s. Despite their superficial similarity, Thoreau’s observation is really quite different from Kierkegaard’s and Percy’s: Thoreau’s sufferers know they are in despair. Yet Thoreau and Percy both home in on an affliction that has come to seem typically modern, and even more typically American, in its unrelenting, poignant ordinariness. How to make it through ordinary Wednesday afternoons poses a confounding moral and spiritual problem—sometimes building to a crisis—for Percy and his characters. It is the rare man—a hero—who realizes that he is a moral desperado and sees his way up and out to a triumph, however incomplete, over everydayness.

What relief, what hope, do the secular caretakers charged with the cure of American souls offer to the populace weary of their psychic burden? Not much, by Percy’s lights. Psychoanalysis was very much in vogue when Percy came of age, and while a medical student he saw his shrink five times a week for four years. In his 1957 essay “The Coming Crisis in Psychiatry” for the Jesuit magazine America, the veteran analysand argues that getting the patient to march in step with his biological imperatives and cultural norms is fast becoming a useless prescription for mental soundness. Such normality is stultifying, an insult to mind and heart.

We all know perfectly well that the man who lives out his life as a consumer, a sexual partner, an “other-directed” executive; who avoids boredom and anxiety by consuming tons of newsprint, miles of movie film, years of TV time; that such a man has somehow betrayed his destiny as a human being.

Percy goes on to paraphrase Pascal on the soul-killing endless diversion that keeps a man from understanding that he is in fact “the center of the supreme mystery”—that “he comes into this world knowing not whence he came nor whither he will go when he dies but only that he will for certain die.” To live your life in this hapless way is to miss the point of being on this earth, and it makes you worse than a fool.

What men truly crave is transcendence, Percy continues. He says that the existentialist philosophers he swears by all agree—even the notorious deicide Friedrich Nietzsche and his atheist epigoni Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre. Of course Heidegger and Sartre proclaimed transcendence for the masses in monstrous political ideologies, one sage serving Hitler and the other endorsing first Stalin and then Mao, but Percy finds them suggestive as diagnosticians of the epidemic malaise. Percy, who went to medical school at Columbia and trained as a pathologist, called himself a diagnostician as well, after the manner of his medical colleague Anton Chekhov. Writing his novels and essays, Percy took his scalpel to the living dead, as he called the sufferers from a surfeit of meaninglessness who populate the upper-middle-class enclaves in which he both lived and set his novels. What distinguishes Percy from the other artists and intellectuals who condemn modern democratic life, and whose heroes find redemption in the universal solidarity of millenarian politics or in the embrace of erotic sorceresses? Percy knows something genuinely better, something that hard experience, some luck, and the authority of an apostle helped convince him was the truth.

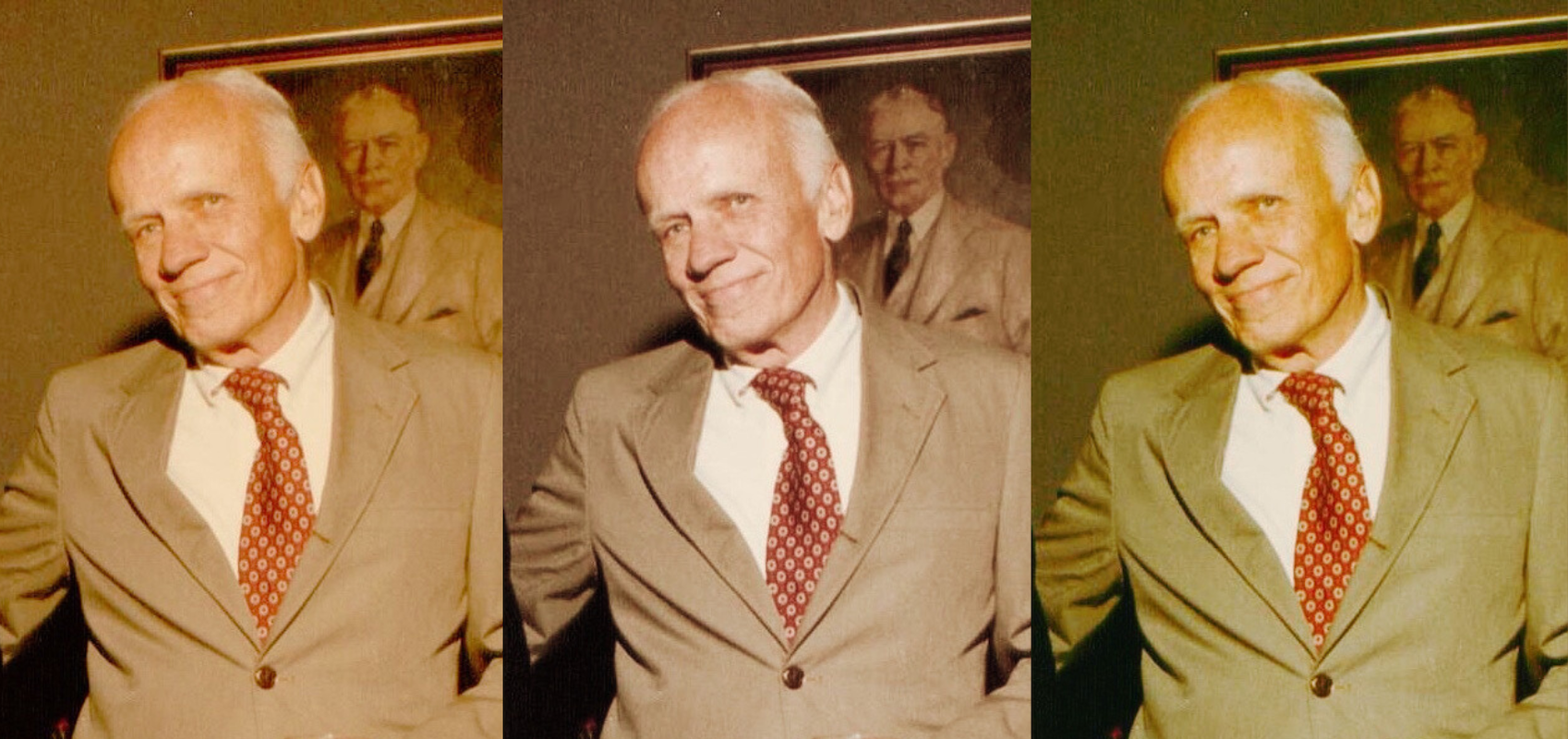

Walker Percy was born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1916, the oldest of three sons. His father, LeRoy Percy, educated at Lawrenceville, Princeton, Harvard, and Heidelberg, was a lawyer with a thriving practice, a testament to his fine mind, first-rate training, and privileged upbringing. Walker grew up in a grand new house adjoining the country club of which LeRoy was president. Darkness, however, encroached upon the model household. In 1925 LeRoy did time in the Johns Hopkins psychiatric hospital, brought low by anxiety and depression. Bandaged wrists marked a suicide attempt, though LeRoy spoke only of an accident in handling broken glass. In July 1929, while Walker was away at summer camp, LeRoy climbed to the attic and killed himself with his 20-gauge shotgun. There was neither marital strife nor financial trouble to explain the self-slaughter. Walker would tell his biographer Robert Coles that his father had suffered from manic depression, a disease with a high violent casualty rate. LeRoy’s father had been prey to the same illness and had likewise committed suicide, Walker believed, though his shotgun death was officially ruled accidental. The dead fathers left a distressing emotional residue: Rumors that LeRoy’s ghost stalked the attic were convincing enough that a famous parapsychologist from Duke University came to check out the scene. The dead man’s estate left his widow, Mattie Sue, and her sons comfortably established, and the family remnant moved to Athens, Georgia.

The intercession of LeRoy’s cousin, William Alexander Percy, shaped Walker’s life for the better as dramatically as LeRoy’s suicide did for the worse. With astonishing goodness and nobility, Uncle Will, a lawyer, planter, and poet in Greenville, Mississippi, the son of a United States senator, a decorated war veteran, and a lifelong bachelor, offered to help raise the boys.

Uncle Will was a marvel of cultivation, his capacious house furnished with the prized possessions of an aesthetic gourmand—lots of the best of everything: Japanese paintings; Moroccan rugs; Victorian bibelots; a bronze statue of Lorenzo de’ Medici; a marble Venus; a Jacob Epstein bust of a dear friend; the latest splendid Capehart phonograph; a record collection heavy on Beethoven and Wagner, but hospitable also to Ravel and Shostakovich; and a library fit to deck out the mind of an embryonic writer and intellectual.

This was not the flimsy refuge against despair that LeRoy Percy’s fancy house on the golf course had been, but rather the home of a man who knew what he was and what he loved, and who dispersed happiness with both hands to all who entered, despite a sadness of his own, which he could not shake. Upon meeting an interesting neighborhood youth, Uncle Will told him that he had some young relations staying at his house, and they would welcome his company. The interesting youth was Shelby Foote, who would become a novelist and the author of an extraordinary three-volume history of the Civil War, an American classic that is as impressive an achievement as Walker Percy’s fiction. Foote and Walker would be best friends for life, each challenging and enriching the other’s mind, and just having a high old time together. The volume of their correspondence is witness to one of the most heartening friendships in American literary life.

For all the joy and promise of this new life, sorrow proved inescapable. In 1931, Mattie Sue Percy drove off a bridge over Deer Creek and died. There was speculation that a heart attack might have sealed her fate before she hit the water, but no autopsy was performed, and exactly what had happened was left in the air. Walker, for his part, was sure his mother had committed suicide—and even attempted murder, for his brother Phinizy had been her passenger. Phinizy had escaped to tell of his mother’s reaching out to him underwater, her foot stuck between the accelerator and the brake. Walker never told his family members of his suspicion, though he did share his angry grief with some friends. He appeared to be staggering along under the burden of an inherited curse.

Many another person would have cracked under the strain. Percy, however, persevered gamely, taking his bachelor’s degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—where Foote was a year behind him—and then his medical degree from Columbia. His immersion in psychoanalysis—the cure that is worse than the disease, as the Viennese wit Karl Kraus put it—seems to have done him no harm, though he never said that it helped him come to terms with the family penchant for violent exits.

During the pathology rotation of his internship at Bellevue Hospital in 1942, he took part in the autopsies of some 125 tuberculosis patients and contracted the disease himself. His case was a comparatively mild one, with a persistent slight fever and non-productive cough—fortunately a far cry from the dreaded galloping consumption. Percy resigned from Bellevue and withdrew to a sanatorium in the Adirondacks. The enforced leisure, like Hans Castorp’s in The Magic Mountain, served an elevated purpose, as Percy examined what he really knew and how he had been living. His scientific cast of mind had taken him far along in the knowledge of human activity in this world but had stopped short of the ultimate questions, under the aspect of eternity. “I had found that [scientific] method an impressive and beautiful thing, the logic and precision of systematic inquiry; the mind’s impressive ability to be clear-headed, to reason. But I gradually began to realize that as a scientist—a doctor, a pathologist—I knew so very much about man, but had little idea what man is.” His physiology and bacteriology textbooks yielded pride of place to the philosophic tomes, novels, and plays of Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Heidegger, Sartre, Albert Camus, Karl Jaspers, and Gabriel Marcel—the existentialists in the vanguard of the modern understanding of what it is to be human. He came especially to cherish Kierkegaard’s improvement on the all-knowing iron-hearted philosophy of Hegel, which “explained everything under the sun except one small detail: what it means to be a man living in the world who must die.” Pondering over his most profound needs was Percy’s salvation. He would later say that catching tuberculosis was the best thing that ever happened to him.

It was upon his recovery from the illness that he became a Roman Catholic. In 1948 he and his wife of two years, whom he had married in a Baptist church, though neither had really been a believer, were baptized as Catholics. No spectacular Pauline conversion had taken place; grace worked in him by degrees over the years, as Paul Elie suggests in The Life You Save May Be Your Own, his joint biography of Percy, Flannery O’Connor, Thomas Merton, and Dorothy Day. Percy’s mind and heart and soul were swayed variously by a friend at Chapel Hill who quietly got up at dawn to attend daily Mass, a Catholic sanatorium patient who defended his faith with steamroller logic and imperturbable deftness, the formidable reputation of Scholastic philosophy, and the gathering awareness that the faith offered a wisdom unavailable to the scientific method. The undercurrent of melancholy in his beloved Uncle Will, a man of integrity, intellectual delight, and personal vigor but no belief in God, helped Percy realize that he needed more for the life of his soul than reason, aesthetic bliss, and warm friendship. And an essay by the Protestant Kierkegaard, “On the Difference between a Genius and an Apostle,” likely provided the more-than-intellectual capstone to Percy’s conversion: Kierkegaard writes, “I have not got to listen to St. Paul because he is clever, or even brilliantly clever; I am to bow to St. Paul because he has divine authority. . . . Authority is the decisive quality.” Unlike the Genius, the Apostle was not trafficking in complicated abstract speculation but bearing news of an event that had actually happened and that he had witnessed. Percy recognized the authority of the Divine Word and set about living accordingly.

Percy changed his life’s direction in other ways as well, abandoning his career in medicine to become a writer. Just what kind of writer was not immediately clear, as he composed a couple of unpublishable novels and a few essays with titles such as “Symbol as Hermeneutic in Existentialism” for which journals such as Philosophy and Phenomenological Research paid him in offprints. His breakthrough came with The Moviegoer, after more than a decade of laboring in obscurity. Over the next twenty-nine years he would publish five more novels, two essay collections, and a mostly light-hearted guide to practical metaphysics, Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book.

In Percy’s second novel, The Last Gentleman (1966), Will Barrett—Alabama native, Princeton dropout, army veteran, maintenance man at Macy’s, and occasional amnesiac—falls in love with Kitty Vaught at first sight while looking through his telescope in Central Park. Themes that would become common in Percy’s work spring into action. Will recalls his father’s happiness when Pearl Harbor was attacked: “The dreadful threat of weekday mornings was gone! War is better than Monday morning.” The deliquescent lushness of a civilization in decay can be heard in Brahms’s “Great Horn Theme . . . the very sound of the ruined gorgeousness of the nineteenth century, the worst of times.” It emerges that Will, when still very young, was listening to the Brahms recording when the sound of a shotgun blast roared through the music: His father had gone up to the attic and killed himself. When there is no longer a war to fight, some men declare war on themselves. Suicide can be better than Monday morning.

Will is a man in need, and he is drawn to the entire Vaught family: the sixteen-year-old Jamie, sick with leukemia; Val, a quite modern nun ministering to impoverished black people; and Sutter, a cynical renegade physician from whom Will hopes to get an answer about how to live. Sutter, though brilliant, seems a dubious choice for healing sage. He is an intellectual steeped in existentialist thought, obsessed with suicide, anticipating with terrible disinterestedness his own death. For him it is not the glamour of evil but the triviality of men’s souls that makes the age hopelessly malignant, and he aches to be out of it: “Americans are not devils but they are becoming as lewd as devils. As for me, I elect lewdness over paltriness. Americans practice it with their Christianity and are paltry with both.”

Once again it is the presence of death that brings out the beauty latent in the hero’s soul. Will and Jamie had gotten along by studiously ignoring the adolescent’s fast-arriving end. At Jamie’s hospital deathbed, however, Will is roused to action by Val’s imperative, from hundreds of miles away, that he either secure a priest to baptize Jamie or baptize his friend himself, though Will is not a Roman Catholic and has no idea how to do it. While Sutter stands apart, sneering at the spectacle, and Jamie defecates in bed, with a scandalizing stench, Will enlists Father Boomer to administer the sacrament. When the priest tells Jamie “the truths of religion,” the patient is just aware enough to ask why he should believe in them. “The priest sighed. ‘If it were not true,’ he said to Jamie, ‘then I would not be here. That is why I am here, to tell you.’” His is the voice of authority, however inadequate this man—hesitant, clumsy, distracted by a stain on the wall—might appear for the job. Jamie seems to say something in response, and Father Boomer asks Will what it was. Will,

who did not know how he knew, was not even sure he had heard Jamie or had tuned him in in some other fashion, cleared his throat.

“He said, Don’t let me go. . . . He means his hand, the hand there.”

“I won’t let you go,” the priest said. As he waited he curled his lip absently against his teeth in a workaday five-o’clock-in-the-afternoon expression.

Shining humanity in the most intense moments has come to be thought the particular virtue of the humanists, as though they were uniquely endowed with the insight, courage, and compassion necessary to deal with extremity. (Think of Rose of Sharon in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, offering her maternal breast to suckle an old man dying from hunger.) Percy restores the claim of the faithful to this human excellence. This passage strikes one as more real—everydayness intruding upon the solemnity—and thus more moving than the famous deathbed scene in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, in which the adulterous unbeliever Lord Marchmain emerges from unconsciousness long enough for an elegant acceptance of the last rites. Here is Percy at his best.

Others of his novels are less successful but still valuable. The Second Coming (1980) resumes the life of Will Barrett fifteen years later; ever haunted by his father’s death and the recovered memory that his father had tried to kill him, Will rants inwardly about the imminence of the Last Days, convinced that he will prove definitively either the existence or the non-existence of God by descending alone into a cave with scant supplies, where he will be saved by divine intervention or die and demonstrate that God is not there at all. After several days underground, a nauseating toothache distracts him from his sacred intention, he struggles to find his way out when his flashlight fails, and he winds up quite improbably falling into a greenhouse. The long-abandoned greenhouse is inhabited by a squatter, a schizophrenic young woman escaped from confinement: Allison Vaught, the daughter of Kitty Vaught, who had married a dentist instead of Will. Allison and Will fall in love, and Will is saved from the living death to which his father’s suicide and attempted murder had condemned him.

Will does not achieve equilibrium and ease but is stricken with a longing more insistent than ever before—for human love and for God. It is not existentialist authenticity he is after, but spiritual abundance. Warmth and uplift are not terms of approbation commonly deployed by serious critics of serious art; they seem more readily applicable to tales of magical children and pictures of blond kittens tumbling over one another in a joyous heap. Accusations of sappiness might seem more in order than words of commendation. But without embarrassment one can praise Percy for establishing warmth and uplift as literary virtues, hard-won in a world that has little place for them.

The last and most ambitious novel Percy wrote, The Thanatos Syndrome (1987), is also the most disturbing, shot through with his vehement hatred of the latest moral improvements in the name of tender-heartedness and the advancement of learning for the relief of man’s estate—to invoke a founder of the modern scientific project to remake inhuman nature and human nature, the better to serve our comfort and convenience and pleasure. Warmth and uplift are the furthest things from Percy’s mind here. He is conducting a crusade of vengeance against enormities that ought to be unthinkable but instead are readily conceived and casually executed.

We have met Dr. Thomas More before, in Love in the Ruins (1971): Psychiatrist and inventor of the Qualitative Quantitative Ontological Lapsometer, he was pursuing three lusty young women at once while trying to avoid the worst of the Bantu uprising, in which determined American blacks established their empire over an enervated white populace. In the later novel, the Bantu heyday is over and it is a new era in America, as the Supreme Court has declared “pedeuthanasia” legal for infants who face “a life without quality,” and assisted suicide for the old is proceeding apace. Dr. More, for his part, is bemused by the increasing incidence of patients who had been overcome by anxiety, insomnia, drug addiction, or sepulchral depression and now are preternaturally alert, chipper, brilliant, and rapturous with the joy of being alive. But there are also cases of quite normal people who suddenly commit acts of mindless violence—typical sufferers of “pure angelism-bestialism,” who “either considered themselves above conscience and the law or didn’t care.” With Sherlockian investigative address, Dr. More and his posse trace these bizarre psychic eruptions to the presence in the water supply of Na-24, heavy sodium isotopes, which in therapeutic dosages produce extraordinary mental acuity and emotional exuberance, but at toxic levels cause regression to instinctual animal behavior. Benevolent scientists, physicians, and government types have been conducting a local trial run of Na-24, with the prospect of going national or even global in due course. Dr. More throws a wrench in the works and saves the day. While he’s at it, our hero breaks up a ring of pedophiles at a leading private academy, who have used the isotopes to drug the children into blissed-out submissiveness, and whose diabolically cunning leader declares blandly that he is undoing two thousand years of hatred for and shame at the human body, replacing them with perfectly natural loving-kindness.

Percy gives his signature line to Father Smith, who has taken to a fire-watch tower after the manner of St. Simeon Stylites, and who reflects continually on the abominations of the twentieth century, conducted in the name of compassion and human perfectibility: “Tenderness leads to the gas chamber. . . . More people have been killed in this century by tender-hearted souls than by cruel barbarians in all other centuries put together.” Percy’s satire burns in this novel, razing to the ground the best intentions of modern scientific humanism, the prevailing wisdom of our time and place, which he has rejected because he recognizes that it is inhuman, and because he knows of something better.

With Saul Bellow he is by far the most intelligent and the most decent of recent American writers. Percy’s impassioned absorption in mid-twentieth-century philosophy nourished his intellect, while his innate and inviolable goodness, an emotional brightness at his core, enabled him to avoid the excesses of such dark luminaries as Heidegger, Camus, and Sartre. Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea had an especially stinging impact on Percy, yet Percy’s stalwart nature prevented this compact nihilist missile from doing lasting damage. For Percy came to understand Sartre’s cry of irredeemable grief—that all is pointless, life a useless interval of pain between two accidents—to be at best a fragmentary truth, conceived of a fascination with one’s own brainpower. To treat it as more than that was to live a lie. Percy could see his way past despair because he had more in common with the two great nineteenth-century religious existentialists, Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky, than with the atheist thinking-engine Sartre. Reason run rampant led inevitably to horror at existence and the embrace of nothingness. Earthly salvation, which might mean freedom from persistent thoughts of suicide, came not from the arrogant mind of genius but from the soul submissive before divine authority.

Percy knew all the ways the mind can go wrong, whether from organic affliction or from a hypertrophied confidence in one’s own intellect. Thorough scientific training gave him the expertise that the age values most, and his philosophizing, strengthened by inborn virtue, revealed to him the deficiencies of that expertise. Appreciative of the wonder and what it takes to be always aware of it, he lived by and wrote with the soul’s knowledge. Walker Percy was wise as few men can hope to be, and we have never been in greater need of such wisdom as we are now. May his reputation grow and flourish.

How to Write a Russian Novel

The Prodigal of Leningradby daniel taylorparaclete press, 256 pages, $21.99 There is of course no generic “Russian…

Knausgaard’s Mephistopheles

Back in college, one of my literature professors once remarked that the first hundred pages of a…

Living with Wittgenstein

In the autumn of 1944, Ludwig Wittgenstein noticed a young doctoral student in attendance at his lectures…