The Pride flag is progressive America’s banner. Before it was unfurled, most gays stayed in the closet. With the advent of Pride, they became out and proud. Over time, gay pride came to be as American as baseball, apple pie, and the Declaration of Independence. The civil rights movement remains a fixture in the official mythology of the nation, but to a striking degree, gay rights has superseded rights for blacks and women as the great symbol of American freedom.

The reasons are many. Gay people are bourgeois. They are just like the rest of us, the boy next door, differing only in sexual preference. A rich white man can’t become black. But his son might be gay. Some women are lesbians; some homosexuals are black. Gay liberation is for everyone, rich and poor, black and white, male and female. It’s the all-American enterprise.

Moreover, gay liberation promises far more than civil rights for blacks and women. The right to same-sex marriage is far more radical than the right to vote or the right to be free from discrimination in employment or housing. The Pride flag represents a new deal for Americans: Government grants what nature denies. We can invent new ways of life in defiance of the most ancient norms. Neither nature nor history can limit us. It’s a stunning view of freedom. It shines more brightly even than the words of the Declaration of Independence, which is why burning the Pride flag today elicits greater opprobrium than burning the stars and stripes.

According to legend, the initial gay rights movement began with a melee at the Stonewall Inn bar in Greenwich Village, when gay patrons fought the police officers who had been sent to round up “deviants.” Due to this episode, what we might call “first-wave queerness” crystallized and became prominent. The Stonewall riots highlighted the plain fact that an active homosexual life diverges from bourgeois values.

First-wave queers participated in the 1960s counterculture. They imagined that straight Americans would join them in fomenting a revolution. In Love’s Body (1966), Norman O. Brown argued that human fulfillment requires overcoming the male-female binary. He preached an “eschatological hermaphroditism” that would inaugurate the perfect freedom of “polymorphous perversity.” Brown’s lyrical book was influential. Its utopian pansexuality led first-wave gay activists to promote the queerest edges and most outrageous behaviors, precisely in order to offend bourgeois sensibilities, and thus hasten the advent of an entirely new social order.

Few leaders of the old queer coalition went as far as Carl Wittman, author of A Gay Manifesto (1970). Heterosexuality, Wittman said, “is a disease,” and “exclusive heterosexuality is fucked up.” Wittman counseled gays to drop the self-hatred. He pushed boundaries. Sex “with animals may be the beginning of interspecies communication,” and “sado-masochism, when consensual,” might be “a highly artistic endeavor.” Perversion must be celebrated!

First-wave queers were united in rejecting the “fantasy of the gay liberals,” as Edmund White wrote in his 1980 book States of Desire: Travels in Gay America. That “fantasy” held that “all homosexuals are the same as everyone else.” White reveled in the hallucinogens, acid trips, alcohol, cocaine, orgies, and anonymous sex that were common in gay scenes around the country. Sexual compulsiveness, he claimed, was a virtue, not a vice. The violation of youthful beauty was an act of benevolence, not a crime. The young would learn the blessings of uninhibited sex.

Not every writer of that period was utopian. As youthful beauty fades, life in the hedonistic utopia gets hard. The greatest gay novel of the era, Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance, ends with Sutherland, an aging protagonist, apparently committing suicide—exhausted, drugged out, and no longer attracting sex partners.

But Holleran’s grim realism did not set the agenda. Gay literature from the first wave championed the randomness and promiscuity of gay lives. Larry Kramer’s 1978 novel Faggots shows gay men targeting “fresh meat” (teenagers) and committing acts of sexual violence. The protagonist, screenwriter Fred Lemish, has sex with more than a dozen men in the novel’s first few pages—all in the pursuit of true love, or so he says.

Raunchy first-wave gays believed that the gay life was superior to humdrum bourgeois life, with its workaday concerns about children, paying the bills, and pleasing a demanding spouse. This sensibility was supported by thinkers who sought to normalize the sexual revolution—not only Brown, but also Herbert Marcuse, Michel Foucault, Wilhelm Reich, and others. Human beings thrived, they insisted, when freed of all social constraints or constructs. Moral discipline served the oppressive capitalist order, they argued. Rebellion, especially sexual rebellion, fostered a liberating socialism. In this critical theory, promiscuous sodomy became a political act, the more public the better.

First-wave queers flouted gender norms in dress and speech. It was during this period that “butch” became stylish for lesbians, and the gay lisp came into fashion. Raunchy subcultures emerged in neighborhoods like Greenwich Village. The queer scene flourished in gay bars, public parks, and public bathrooms. Orgies were institutions. A gay press was built.

Gays relished their difference, manifest in their embrace of the heretofore derisive word “queer.” And they lived that difference. Alan Bell and Martin Weinberg, authors of Homosexualities: A Study of Diversity Among Men and Women (1978), found that 26 percent of gay men had one thousand or more sex partners in a lifetime, while 41 percent had a more modest fifty to five hundred partners. Around three-quarters estimated that the majority of their sexual encounters were with strangers. A 1984 study found that only 4.5 percent of male homosexuals practiced sexual fidelity. First-wave queers saw these statistics as signs of achievement: Gays were in the vanguard of a new way of living!

Gay groups in the 1970s and ’80s included the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, Gay Liberation Front, Radicalesbians, The Daughters of Bilitis, and, after AIDS came on the scene, ACT UP. Popular sentiment was negative, however. During the 1970s, former Miss America Anita Bryant led a successful campaign, “Save our Children,” to allow private discrimination against gays. At about the same time, Canadian authorities raided a gay newspaper that was sympathetic to “boy-love.” Some gays owned the insult. The North American Man-Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) was founded in 1978 to confront bourgeois morality. The Village People (referring to Greenwich Village) memorialized macho-gay fantasies. Their classic song “Y.M.C.A.” valorized older men’s preying on the young.

Embracing raunch was central to first-wave gay activism. If gays were intransigent and loud, Americans would be forced to accept their bathhouses and orgies and learn to live with them. The mainstream would become much, much queerer and politically radical. As a gay activist writes in Kramer’s Faggots, “we shall make our presence known!, felt!, seen!, respected!, admired!, loved!” Queer Nation, founded in 1990, was the last great raunchy gay group in the first wave. It promoted the slogans “We’re here. We’re queer. Get used to it,” and “Out of the closets and into the Streets.” Queer Nation compared itself to an army, and its manifesto was a model of anti-bourgeois contempt: “Every time we fuck, we win.”

As a strategy, however, raunch contained serious ambiguities. On one hand, raunchy gays refused to lie about their lifestyles. They contrasted their deviance with a supposedly stultifying mainstream. They saw themselves as subversive shock troops, agents of revolution. On the other hand, they wanted, somehow, respect from a new, queerer American mainstream. Their complaints about discrimination and demands for acceptance sat uneasily with their self-image as bold subversives. Their existence as “the Other” presupposed the continued dominance of the mainstream, and yet they wanted a mainstream that welcomed drag queens, pedophiles, bull dykes, and every other weirdo, not as “normal” people who happened to have gay sex, but as weirdos.

First-wave gay liberation failed. America did not become queerer. Gay activists were compelled to shift their strategy. They began to portray homosexuality as a slight deviation from bourgeois life. Thus was born second-wave gay liberation, which downplayed queerness.

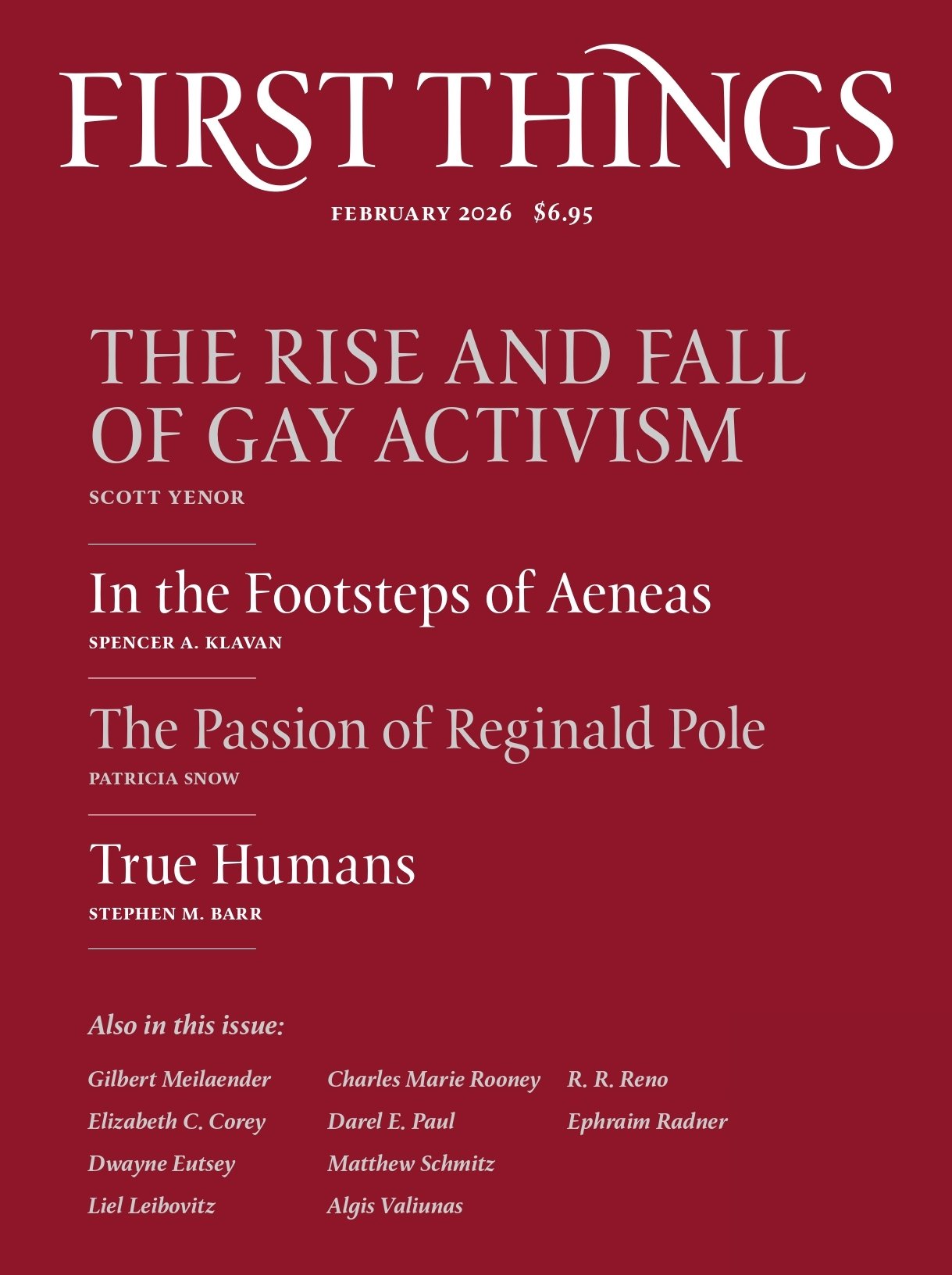

Gilbert Baker, an artist and gay activist, sewed the first Pride flag in the late 1970s at the behest of Harvey Milk, who wanted a symbol of hope and confidence that would encourage militancy among gays. Later gay rights advocates reframed the Pride flag as a symbol of safe, sound, and beneficent diversity. In 1999, Bill Clinton designated June as Pride Month to commemorate the Stonewall riots. Clinton’s decree gave official sanction to a new founding myth for the gay movement: The pervasive repression and homophobic intolerance of American society were being justly defeated by the noble struggle of gays for respect, pride, and recognition. Gay liberation became gay rights. It sought inclusion rather than revolution and promised to fulfill mainstream America’s self-image.

The morality tale was created in the early 1990s by gay activists who were facing setbacks. Americans are trained to believe that the arc of history always bends toward social tolerance. But this is not the case. The ways in which minorities present themselves will affect political judgments and legal constructs. As gays came out of the closet after Stonewall and Americans became aware of gay sexual practices, public opinion tilted against gay liberation. In 1990, polling indicated that more Americans thought sexual relations between two adults of the same sex were always wrong (73 percent) than had been the case in 1973 (70 percent). “The gay revolution has failed.” So begins Marshall Kirk and Hunter Madsen’s 1989 manifesto After the Ball: How America Will Conquer its Fear and Hatred of Gays in the 1990s. A new gay image was needed.

Kirk and Madsen saw gay rights in terms of coalition politics. The gay issue presented a puzzle: how to get Americans to accept the gay coalition, which consisted of gay men and lesbians, as well as exhibitionists, pedophiles, drag queens, cross-dressers, sadomasochists, orgy-lovers, zoophiles, and countless others.

Kirk and Madsen observed that first-wave gay revolutionaries had put forward “screamers, stompers, gender-benders, sadomasochists, and pederasts.” This approach confirmed “America’s worst fears” about the excesses and dangers of gay liberation. Mass pro-gay demonstrations and militant Pride parades turned into “ghastly freak shows” during the 1970s. These realities disgusted American sensibilities.

For the gay coalition to succeed, a new approach was needed. Kirk and Madsen argued for platforming “normal” gays while hiding the weirdos. Gays should be depicted “in the least offensive fashion possible.” With handsome, non-threatening, and normal-looking gays as the face of the coalition, the “homo-hating beliefs and actions” would “look so nasty that average Americans will want to dissociate themselves from them.” Kirk and Madsen advised a canny strategy: “The public should not be shocked and repelled by premature exposure to homosexual behavior itself. Instead, the imagery of sex per se should be downplayed, and the issue of gay rights reduced, as far as possible, to an abstract social question.” Being gay had to become boring. Partner benefits, hospital visitation privileges, dignity, and affirmation were to be presented as the essential concerns of gay life.

The second-wave strategy was adopted. The Queer Liberation Front, with its Marxist overtones, was sidelined. Gone was the Pink Triangle, which implied that American society was akin to a Nazi concentration camp. The North American Man-Boy Love Association must “play no part at all,” Kirk and Madsen write, in this new movement. Indeed, one tactic was to accuse opponents of gay rights with unjustly equating the “love that dare not speak its name” with pedophilia.

As the raunchy image of first-wave gay activism was suppressed, the Human Rights Campaign became the leading voice for gay rights. It was portrayed as a natural extension of the nation’s commitment to civil rights. The battle was as American as apple pie.

It worked. Weirdos stayed in the shadows, while normie gays defined the movement. Hollywood gave us Philadelphia in 1993, a movie hewing to Kirk and Madsen’s script. Homophobes in the film are cruel, bigoted liars, perhaps suppressing their own homosexual longings. Tom Hanks, whose character has AIDS, never kisses his lover, played by Antonio Banderas. The couple is made to suffer and attract the audience’s sympathy.

In the second-wave script, gays have high tastes, obey the law, and practice monogamy (sort of). They are competent and honest boys next door. In response to this portrayal, which was widely adopted, the number of Americans who thought sexual intimacy between two people of the same sex was always wrong dropped from 73 percent in 1990 to 62 percent in 1993. It sank to below 50 percent in 2008 and hovers around 33 percent today. (It registers in the single digits in Sweden and the Netherlands and below 20 percent in much of Western Europe.)

Second-wave gay rights advocates aimed at stopping all denunciations of gays, lesbians, and allies. To notice any sign of degeneracy within the gay scene made one a homophobe. Gays who pointed out the degeneracy within their own scene were denounced for abetting critics of the movement. In the 2000s and 2010s, the policing of criticism intensified. Accusations of homophobia could end or compromise careers. Opposition to same-sex marriage was stigmatized. Those who violated the new prohibitions, such as Brendan Eich of Mozilla, were released from their jobs or, in the case of people like Mark Regnerus, were investigated at the universities where they taught.

The second-wave strategy has been stunningly successful. Few on the right whispered about overturning Obergefell in the years immediately following that closely contested decision. Think tanks that had opposed gay rights and same-sex marriage switched to abortion, religious liberty, or the ill effects of technology. Safer topics. Scholars made prudent decisions to avoid topics that might gain the ire of gay activists. As a result, objective studies of gay distinctives are difficult to find—and respectable scholars hardly ask questions about gay fidelity, mental health, or life expectancy.

But for all its success, second-wave gay activism contained ambiguities. Was it urging propaganda in order to win acceptance? Was the old queer ambition to be out and loud still operating under the surface? Or did second-wave gay activism seek moral reform among gays? Was the presentation of “normie” gays meant to set a standard in the gay community, rather than just shift public opinion? The answer: Yes.

“Straights hate gays not just for what their myths and lies say we are,” Kirk and Madsen write, “but also for what we really are.” Kirk and Madsen advocated better propaganda, but they also called for behavior modification among gays. Reformed gays would be less sexually compulsive, narcissistic, nihilistic, self-indulgent. Their interest in having sex with minors would lessen, and fewer would have sex in public parks, bathhouses, gay bars. Gays would be less obsessed with finding youthful, handsome sex partners, and would cease their cruel shunning of the old and ugly. Gay men with AIDS and other communicable diseases would desist from unprotected sex with other men. Fidelity and enduring relationships would come to be honored among gays. Andrew Sullivan made a contribution to this vision of acceptance combined with reform. His 1995 book Virtually Normal sought to convince straights to embrace same-sex marriage while arguing that bourgeois marriage would tame gays.

But second-wave gay activism never could bring itself to embrace “normal” homosexuality. Kirk and Madsen were of two minds. They saw the public necessity of emphasizing “safe” homosexuality. “Gays must, at this moment, prefer reveille to reverie”—which is to say, suppress the impulse toward debauchery for the sake of message discipline. The gay revolution, they promised, would revolutionize public opinion. First gain respect for “monogamous” gays and lesbians, then extend bourgeois approval to those still in the closet—the drag queens, cross-dressers, butch dykes, and, perhaps, pedophiles. “In time, as hostilities subside and stereotypes weaken, we see no reason why more and more diversity should not be introduced into the protected image.” After victory for “normal” gays was secured, the weirdos could venture out of the closet.

Kirk and Madsen bet that when same-sex marriage won the day, it would be because Americans had conquered their fear and hatred of the full spectrum of the gay coalition. A people accepting same-sex marriage would not be interested in drawing moral lines of any sort when it came to sex, they thought.

Whether or not Kirk and Madsen correctly predicted the long-term consequences of the gay rights victories of recent decades, the second wave of gay liberation is giving way to a third wave, one that aims to license the full panoply of sexual deviance. Cross-dressers have come out of the closet. Academics have tried to mainstream minor-attracted persons. Queer pedagogy has flooded into elementary school, and drag queens read to children in public libraries.

Players from the old and confrontational gay rights revolution had been sidelined while public opinion was being transformed. Now, in the third wave, they believe the coast is clear. They are going public and celebrating sexual weirdness. In this way, they echo the first-wave queers and their affirmation of the most extreme forms of deviance. But the third wave also wants to follow the playbook that led to Obergefell. It emphasizes the liberal language of consent, affirmation, and human dignity, not the old vision of anti-bourgeois revolution. “Minor-attracted persons” are trying to win acceptance for an orientation, not a psychological disorder—a rhetoric that copies exactly the second-wave playbook. Transgender youth are innocent and vulnerable, and they must be supported and affirmed so that America can fulfill its vocation as an inclusive nation. Drag queens are just being their authentic selves (as Darel Paul has shown in these pages).

Weirdos act like it’s 1975, but they talk the language of 2015. Drag queens, pedophiles, and gender-benders demand respect, dignity, and affirmation. Transing kids and promoting gay sex to youngsters are now included in comprehensive sex education under the banner of “best practices” for promoting the mental health of children and encouraging tolerance.

But third-wave gay activism has its ambiguities as well. It embraces the second wave’s achievements, especially the successful capture of the language and prestige of civil rights. But because the third wave pushes acceptance of “out and proud” deviance, it inevitably becomes revolutionary, as the first wave recognized. And revolution means an assault on mainstream American sensibilities, which, perhaps, prepares the ground for a reaction or “backlash.”

This ambiguity is evident in the T that has been added to LGB. Transpeople are gender benders whose appearances and behaviors do not fit society’s expectations for their biological sex. Third-wave activism insists that they are different, yes, but “normal.” They need to “transition,” but otherwise are just like everybody else. The imperative is acceptance and inclusion.

But unlike gays at a sex party, transpeople are transgressive in public. Everyone must pretend that the man playing women’s volleyball is a woman—or commit a civil rights violation. Misgendering is likewise a civil rights violation in several states. Trans propaganda of normality is coupled with a fervent need to denounce and cancel transphobes. Birth certificates and government IDs must be changed. Euphemisms such as “child-bearing persons” must be employed.

The trans movement is a freak show with totalitarian impulses. The same-sex movement got many Americans, including a majority of the Supreme Court justices, to pretend to believe that marriage only incidentally concerned the having and raising of children. The trans movement demands that people forget that there are only two sexes—an even more fundamental human truth. And that kind of forgetting entails a revolution more far-reaching than anything first-wave queers imagined.

Third-wave gay activism even threatens second-wave achievements. Americans were sold same-sex marriage with abstract appeals to lifestyle and dignity. The appeal for acceptance becomes more difficult when Americans learn about “married” gay men who adopt young boys or see lesbians holding hands or gay men necking in public places. Just as ultrasounds brought home to many Americans the reality of unborn children, Instagram posts of manly gay people celebrating the fruits of surrogacy bring the reality of gay marriage home. Kirk and Madsen wanted to keep the reality of gay sex and same-sex marriage hidden, but eventually people notice—and judge. Few television shows depict gay sex, despite the fact that polls say that the majority of Americans support the right of gays to be depicted on television. The “conservative” actions of entertainment producers speak more loudly than polls. It’s not clear that the “wins” of recent decades are as deep and secure as Kirk and Madsen had hoped.

Stretching the category of respectability to cover the raunchy and weird hollows out the whole concept. In 2015, when the arc of history seemed to bend toward limitless inclusion, proceeding from same-sex marriage to the trans cause looked like a winning approach. The Human Rights Campaign went all in. Corporations sold tucking underwear for children. Trans propaganda was everywhere. Today, the same-sex marriage brand is tarnished by its connection with the transing of kids, the platforming of drag queens, and the grooming of children with comprehensive sex education. Pride parades seem passé, and some sponsors have backed away from them.

To be sure, supermajorities continue to support same-sex marriage. But the trends are not favorable to third-wave gay activism. According to Gallup, from 2022 to 2024, Republican support for same-sex marriage dipped from 55 percent to 46 percent, while Democratic support fell from 87 percent to 83 percent. An AEI poll shows an astounding 11-point drop in support for same-sex marriage among Gen Z between 2021 and 2014 (from 80 percent to 69 percent). Ipsos, a French marketing firm, found that in the past three years, support for same-sex marriage had dropped in eighteen of the twenty-six countries surveyed. In 2014, near the height of the “after the ball” strategy, nearly two-thirds of Americans supported the right of same-sex couples to adopt children. The number increased to 75 percent in 2019. Future polling will, I predict, show declines in support.

The question we need to ask is how to accelerate these trends. During the same-sex marriage debate, it was taken as self-evident that the first side that talks about sodomy loses. The left knew it had to hide reality; the right feared looking intolerant. As a result, neither side brought up anal sex. Both sides stuck to abstract notions of rights, dignity, and the proper definition of marriage.

The public’s uneasiness with the realities unleashed by gay liberation suggests a new strategy, or a return to an older one. As the third wave becomes more frank and open about what it seeks to make mainstream, social conservatives must become more frank and open about what they seek to promote and censure. Trimming off the excesses of the gay revolution is a containment strategy that does not work. Yesterday’s sexual revolution is institutionalized and awaits its next revolutionary moment. More boldness is needed.

The first step involves exposing the second-wave strategy. That strategy foregrounded the virtually normal, and it did so knowing that it would thereby empower the abnormal. The plan was to queer the mainstream. The public needs to understand the connection between same-sex marriage and trans ideology.

Research into and reporting on the reality of gay life was suppressed under second-wave gay activism. We need to reverse this. Funding must be provided for scholarly studies of gay adoption, gay life expectancy, and other features of gay life. Stories should be written about the gay scene in various cities. Gay activists who adopted the second-wave strategy worked hard to shut down this work in the past, because they knew that scholarly research and journalistic exposés would hurt their cause. The right complied, for a variety of reasons.

Such compliance must end. We need to know what proportion of male-male marriages remain monogamous, in comparison with male-female marriages. It is easy to find up-to-date data on the number of sexual partners for straight men and women, but difficult to find the same data for gay men. The CDC should collect those numbers, too. Studies must be done on the mental health and life outcomes of children raised in same-sex households.

Edmund White’s States of Desire surveyed the gay scene in seven American cities. Gays celebrated their deviance in 1980 through gay journalism and literature. Opponents of the gay revolution took the same evidence and systematically presented it to the public, to good effect. Both the deviants and their opponents were silenced by second-wave gay activism.

The frankness and ambition of third-wave activism constitute an opportunity. Well-reported stories can expose surrogacy as a practice that allows doctors to become rich by peddling children to gay couples. We need profiles of discarded surrogates and accounts of the experience of children who lack opposite-sex parents, to say nothing of children adopted and then sexually abused.

The second-wave dignity revolution was always an unstable gambit, meant to hide reality and suppress judgment. Now the unpleasant reality of raunch is coming into the open, not least because of the misjudgment about the trans movement. This reality is creating a vibe shift among many Americans. The arc of history need not bend toward acceptance of sexual deviance. Today, it is possible to imagine the rollback of the gay rights revolution.