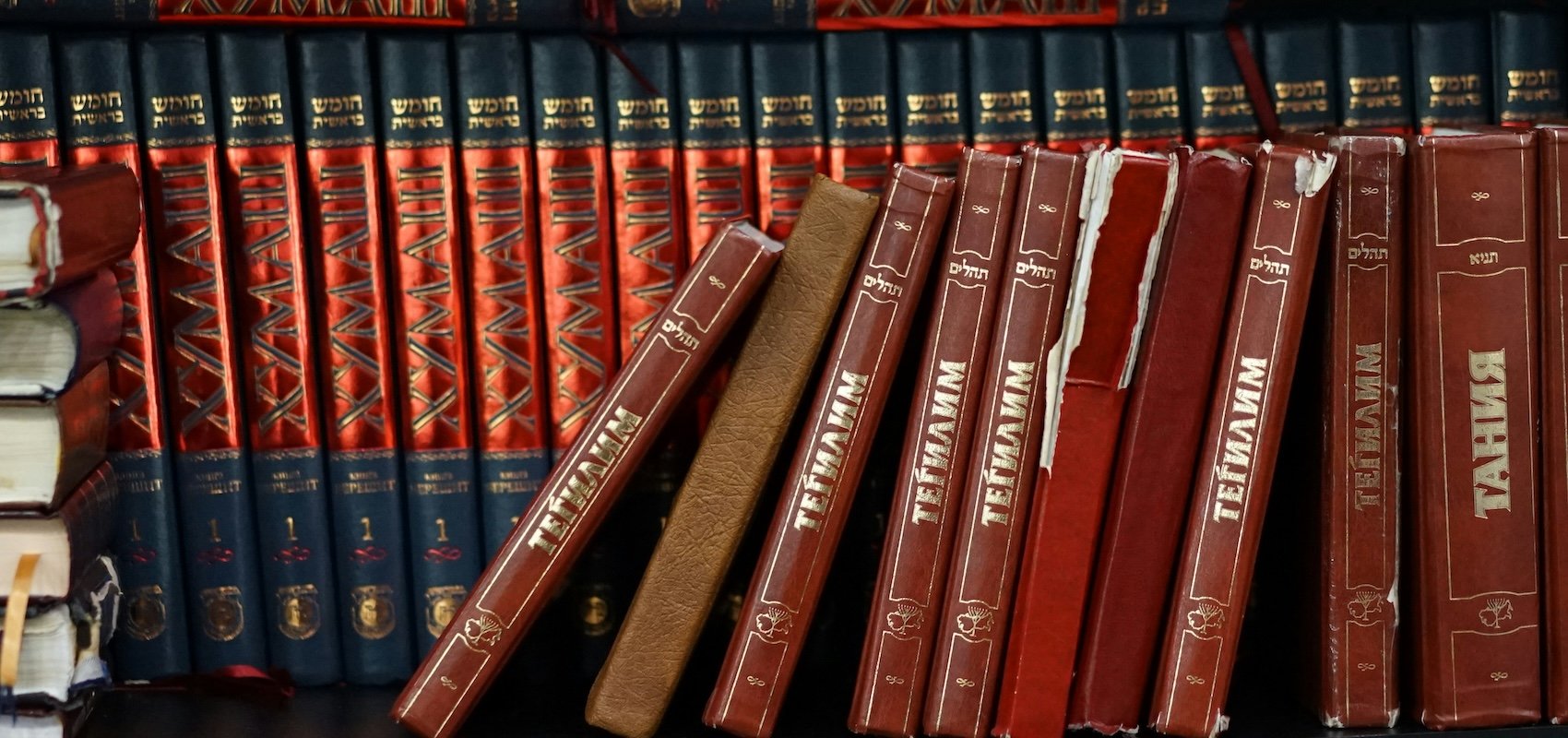

In the introduction of Jewish Roots of American Liberty, a new collection of essays and documents edited by Wilfred M. McClay and Stuart Halpern, McClay declares that the Jews “provided the deep metaphysical, moral, and anthropological foundation upon which much of the American experiment in democratic self-government was erected.” The book contains essays by Mark David Hall, Daniel Dreisbach, and other distinguished scholars. Halpern’s entry explores the significance of David, Esther, Samson, Elijah, and Daniel in American history and culture. Tevi Troy recounts what the Bible meant to different presidents. The book also includes George Washington’s correspondence with Hebrew congregations and Calvin Coolidge’s 1925 speech “Jewish Contributions to American Democracy.” First Things Erasmus speaker Meir Soloveichik explains “What Jews Mean to America,” while Eric Cohen details the significance in America today of Jerusalem and the state of Israel, which “stir so many Christian souls with such spirited resolve.”

Christopher R. Seitz’s The Predestinate: Ecclesiastes and the Man Who Outshone the Sun King unexpectedly pairs the author of Ecclesiastes with the finance minister of King Louis XIV. Before his fall, Nicolas Fouquet was “the best-connected man in France,” overseer of the French treasury, collector of fine art and manuscripts, builder and resident of the famed Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte, and, eventually, the purported author of Les Conseils de la Sagesse, written in prison after Fouquet’s arrest for embezzlement. His thoughts follow the wisdom and spirit of Ecclesiastes. The author of the Old Testament book was, Seitz says, “a man who, though once enormously wealthy and endowed with great wisdom, lost everything.” Fouquet did, too, and was probably mostly innocent of the charges made against him. Hence, “the parallels with Fouquet are obvious.” Ecclesiastes is also a source of personal inspiration for Seitz. He discloses that the verses in chapter 12 “grab a hold of me spiritually and emotionally.” The book is not a “tribute to pessimism and futility,” as often thought, but a map of how to “become a different [and better] man.”

From Sinai to Rome: Jewish Identity in the Catholic Church is a collection of essays “concerned with recovering the Jewish dimensions of the Gospels and the Church so that Catholicism may recover its full ecclesial dimensions as consisting of Jews and gentiles under the Messiah of Israel.” At issue is the supersessionist understanding, in which the Jewish covenant has been nullified by the coming of Christ. Contributors address the Jewish origins of Jesus and Mary, Aquinas on the Jews, the very idea of “Hebrew Catholics,” and what it means for a Jew to convert to the Church. How Catholic universalism accords with Jewish particularism, along with other tensions between the faiths, is discussed. Editors Angela Costley and Gavin D’Costa have a goal: to “deep[en] our Catholic appreciation of the Jewish church.” They believe that Catholic faith expands when it is understood in continuity with ancient Judaism. As one essay says, “After all, at the most primitive stage of her formation, the Church was a strictly Jewish undertaking.” Another one quotes Cardinal Newman: “The Jewish Church and the Christian Church are one.”

In Explaining Israel: The Jewish State, the Middle East, and America, Peter Berkowitz combines intellectual depth with firsthand reportage to explain a situation that leaves Americans often perplexed and dismayed. The volume collects forty columns written by Berkowitz from 2014 to 2024, the topic being the complex place and continuing story of Israel in recent times. Berkowitz’s commentary on the October 7 attacks maintains an admirable objectivity and prudence at a time of horrified worldwide reaction. The goal is to inform, not to provoke. His September 2016 assessment of the deal Obama made with Iran concludes by asserting that the deal made Iran more dangerous and destabilizing, not less so. But Berkowitz treats the error analytically, attributing it to “Obama’s unconventional version of balance-of-power politics,” not to lesser motives. That’s the tone of the entire book, a ten-year record of the region by one of the most reliable observers we’ve got.

Modern Jewish Worldmaking through Yiddish Children’s Literature, by Miriam Udel, contains dense historical accounts and careful readings of Yiddish culture and the children’s literature it produced. We learn, for instance, of the career of Leyb Kvitko (born 1890 or 1893), the most popular Yiddish children’s author in the Soviet Union, who had to write stories in a polity growing ever more hostile to the “bourgeois family.” He composed stories of children with absent or bad parents, who resort to their own initiative and, eventually, receive kind support from the state. Ultimately, officials weren’t sufficiently impressed. In August 1952, Stalin gave orders for him to be executed.

Finally, a note about The Golden Thread: A History of the Western Tradition, a new textbook to which all history teachers should pay close attention. The authors are noted historians Allen Guelzo and James Hankins. The first volume is subtitled “The Ancient World and Christendom.” I include it here because it has sections on “Ancient Israel,” “Exile and Return,” “The Judaism of the Second Temple,” and “Jewish Revolts.” The authors take time to explain the theological meaning and historical status of Israel, the covenants, ideas of justice and equality, God’s punishments, and so on, up to the emergence in Galilee of Jesus. This is a legacy not always given sufficient attention in Western Civ layouts. I recommend The Golden Thread for classical, Christian, and Jewish schools everywhere.

Living with Wittgenstein

In the autumn of 1944, Ludwig Wittgenstein noticed a young doctoral student in attendance at his lectures…

Briefly Noted

Kevin James and Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke rarely appear side by side, even in print—the back-cover endorsements…

The Scandal of Judaism

Christianity has been marked by hostility toward Jews. I won’t rehearse the history. I’ll simply propose a…