Hope,” wrote the German-American polymath Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, “is the deity of youth.” Wholly dependent on adults, children have little scope for action and “can only hope for the best.” But we can’t live on hope forever. Children enter responsible adulthood when hope yields to love—love for a woman or man, devotion to an unsought mission, torchbearing a life-defining cause. Inspired by love, the young break out of old conventions and habits, certainly their own, sometimes also the conventions of their tribe. Yet a professional enthusiast isn’t a full man either: “The everlasting idealist . . . tries to prevent inspiration from ever coming true.” Once the honeymoon is over, passion must solidify, boiling inspiration will simmer. To become fruitful, seeds sown in exuberance need to be cultivated, ploddingly, by faith. As the Spirit descends so the Son may take flesh in Mary’s womb, so inspiration is confirmed by incarnation.

Hope, love, faith: The three theological virtues, though not in Pauline order, form the tripartite shape of a good life—childhood, youth, maturity. You can’t skip over any phase. If some overpowering love doesn’t shatter the chrysalis of my childhood, I’ll never surpass the passivity of childish hope. Without the memory of my original inspiration, I won’t keep slogging through long seasons of slow, sometimes imperceptible germination and growth.

Among other things, Rosenstock’s sketch of life stages highlights the near-inevitability of a “generation gap.” Here’s the paradox: Children must grow up, but they don’t become fully-realized human beings if they simply replicate their parents. They have to leave father and mother and cleave in love to wife or husband, cause or mission. Rupture with the past is the only pathway into the future.

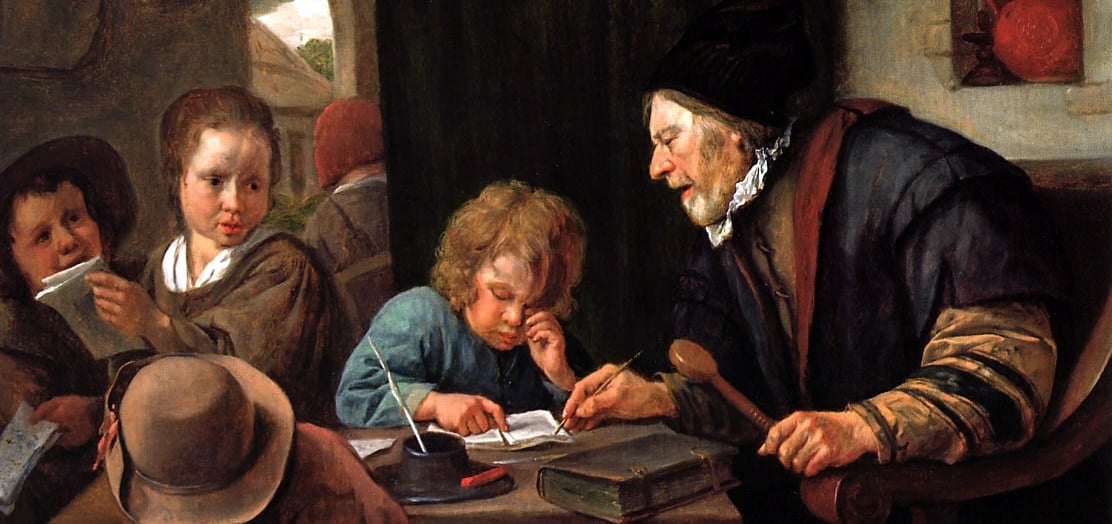

How then can the sons be turned to their fathers, fathers to their sons? What prevents the young (men) from renouncing the past in a frenzy of revolutionary nihilism? In “Man Must Teach,” Rosenstock’s seminal essay on education, he argues that the classroom harmonizes generations by harmonizing time. A classroom doesn’t have to be part of a formal institution; it can be the dining room table, a weekend fishing trip, a liturgy, a conversation over coffee. Whatever its form, the classroom brings a teacher together with a student or students in the same place at the same time. Despite appearances, teacher and students don’t meet as “contemporaries” but as “distemporaries.” The teacher is always “older,” if not in age at least in his exposure to the material; students are always “younger” because they enter the class as innocents venturing into an unexplored country.

Distemporaries forge a common present only when “they admit that they form a succession, if they affirm their quality of belonging to different times.” And the classroom works its magic only when it’s infused with faith, hope, and love. Students must trust and entrust themselves to the wisdom of the teacher, yielding their shapeless souls to his sculpting. The “aged” teacher must die to possibilities and plasticities that are still open options to his students. In self-sacrificial love, he hardens himself, foreswears youthful play, and gives his students a taste of his life-and-death struggle for truth. Student faith mingles with the teacher’s love to produce a common spirit of hope that animates the classroom.

As a reward for his renunciation, the teacher overcomes death, putting his imprint on a future he won’t live to see. Teachers are driven by a “forwardizing force,” students by a “backwardizing” force that seeks to hold conversation with the past. Teachers throw out a feeler to the future, students a feeler to the past. When forwardizing teachers and backwardizing students come together in love and faith, they form a “body of time” that old and young inhabit together.

To succeed in this essential vocation, the classroom must be held in a delicate equilibrium. For several generations, it hasn’t. Teachers and parents buddy up with the young as if they were contemporaries. They’re reluctant to submit to the burdens of being “old” and are stirred by the same lust for novelty as the young. Many have lost confidence in the past they represent, or never had a chance to receive their heritage in the first place. Unmoored from a teacher’s past, without the guidance of a teacher’s love, the young lose faith in the old, and the arid classroom that results is bereft of hope. Under these conditions, the youthful explosion of inspiration turns purely destructive, and we’re left with generations of disinherited young (men) who misconstrue their homelessness as oppression. Our hope lies in the Spirit, who alone can revive the theological virtues and form classrooms that bind up the wounds of time.