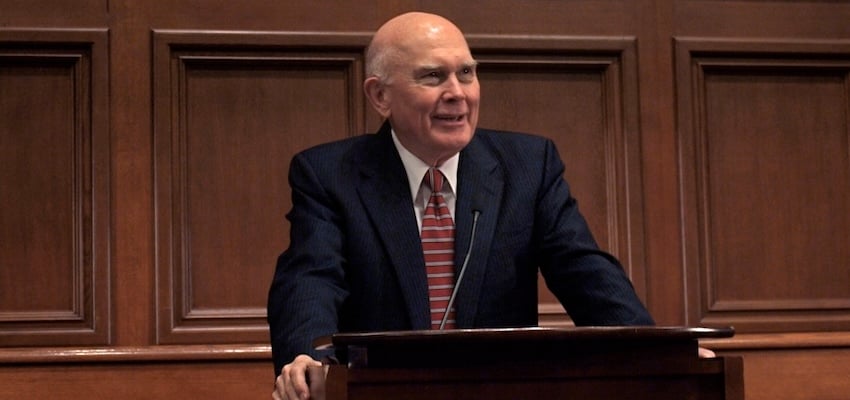

Following the passing of Russell M. Nelson, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has named its eighteenth president. Dallin H. Oaks, a former lawyer and Utah Supreme Court Justice, will take up the mantle and lead the Church’s more than 17 million members. In many regards, Oaks becomes the equivalent of the pope for Latter-day Saints. Even more than the Supreme Pontiff, however, the president of the LDS Church is considered by the faithful to be a living apostle and prophet, inheriting the dual mantle of Peter and Moses. In his new capacity, Oaks will provide spiritual counsel and oversee global church operations. Beyond that, he will counsel Latter-day Saints on how to engage with the world. His ascension comes at a moment of deep fracture in American civic life. In recent years, Oaks has emerged as a sort of civic theologian, offering a vision of how faith can inform public responsibility in a divided republic.

Before his call to full-time church service, Oaks had been a law clerk to Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Earl Warren, a law professor at the University of Chicago, the president of Brigham Young University, and a Justice on the Utah Supreme Court. He was called to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, the Church’s second-highest governing body, in 1984 at age fifty-one. As an apostle, he was asked to relinquish his secular career and spend the remainder of his life in service to the Church. Traditionally, the longest-serving apostle becomes the Church’s president. Oaks, at ninety-three, became the Church’s president on Tuesday, October 14.

In recent years, Oaks has laid a distinctly Latter-day Saint articulation of how faith informs civic responsibility in a diverse republic. In a landmark talk to Church members in 2021, Oaks outlined five elements of the U.S. Constitution that he calls “divinely inspired,” including popular sovereignty, federalism, the separation of powers, the protection of rights, and the rule of law, each of which contribute to a political system in which moral agency is honored and protected. In addition to calling on Latter-day Saints to uphold the Constitution and take active part in the political process, he taught that “on contested issues, [Latter-day Saints] should seek to moderate and unify.”

Speaking to an audience at the University of Virginia later that year, Oaks expressed distress “at the way we are handling the national issues that divide us.” He called on Americans to find “a way to resolve differences without compromising core values.” This involves a recognition that we live in a pluralistic society and that getting along “requires us to accept some laws we dislike, and to live peacefully with some persons whose values differ from our own.” Oaks uses the example of the tension between nondiscrimination laws and religious liberty protections. He counsels against using reductive labels like “bigot” or “godless,” and instead to engage in good-faith negotiations based on mutual respect, to “seek to accommodate [worthy arguments] consistent with the most important interests of all sides.”

An example of Oaks’s civic theology in action is the so-called Utah Compromise, a 2015 bill out of the Utah state legislature that included nondiscrimination protections for the LGBT community while also protecting targeted religious exemptions. Here, the Church engaged in negotiations with Equality Utah, a gay advocacy group, and forged a compromise to protect the most important interests of either party.

To many religious conservatives, compromise is a dirty word. How can one compromise on a moral issue, after all? It is important to note that the doctrinal teachings of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have remained consistent: marriage, according to the Church, is a lifelong commitment between a man and woman. Still, Oaks and the Church are clearly comfortable compromising to some degree on matters of public policy. Thus, there appears to be a distinction between doctrinal integrity and civic accommodation. Is this just a practical necessity? A means of survival in a secular age?

Oaks would say “no.” In an address in Rome in 2022, he “maintain[ed] that followers of Jesus Christ have a duty to seek harmony and peace.” Elsewhere, he has pointed to Jesus’s teaching, “Blessed are the peacemakers,” and Paul’s admonitions to “follow after the things which make for peace” and to seek “if it be possible [to] live peaceably with all men.” In other words, to Oaks, it is a Christian imperative to engage in negotiations, and yes, compromise, toward social peace and harmony.

This does not mean one must abandon one’s sincerely held moral convictions or that people of faith must retreat from the public sphere. “All are lawfully privileged and morally obligated,” Oaks teaches, “to exert their best political efforts to argue for what they think is most desirable.” It does mean, however, that at least Latter-day Saints will need to engage in political debates with an eye toward building bridges, recognizing the inherent worth of their political adversaries and seeking, to the extent they are able, to accommodate their reasonable interests.

I suspect that some readers will view the LDS Church’s emphasis on civic charity and mutual accommodation as a sort of betrayal. But to dismiss Oaks’s civic theology as a surrender to secularism is to misunderstand it. He is not urging the dilution of Christian teaching on matters of moral importance but the application of Christian charity to political life. His civic theology is rooted in the conviction that building a harmonious pluralistic society will entail the hard work—and the Christian virtues—of persuasion, compassion, and love unfeigned. Perhaps rather than revealing a weakness of resolve, this civic theology of peacemaking offers precisely what is needed to restore our rupturing social fabric.

The Countryman–Foreigner Distinction (ft. Matthew Crawford)

In this episode, Matthew B. Crawford joins R. R. Reno on The Editor’s Desk to talk about…

James Talarico’s Backward Christianity

James Talarico wants to “reclaim Christianity for the left.” That’s the title of the New York Times…

Just War Theory and Epic Fury

The machines of war have sprung into action once again in the Middle East. Bombs are falling…