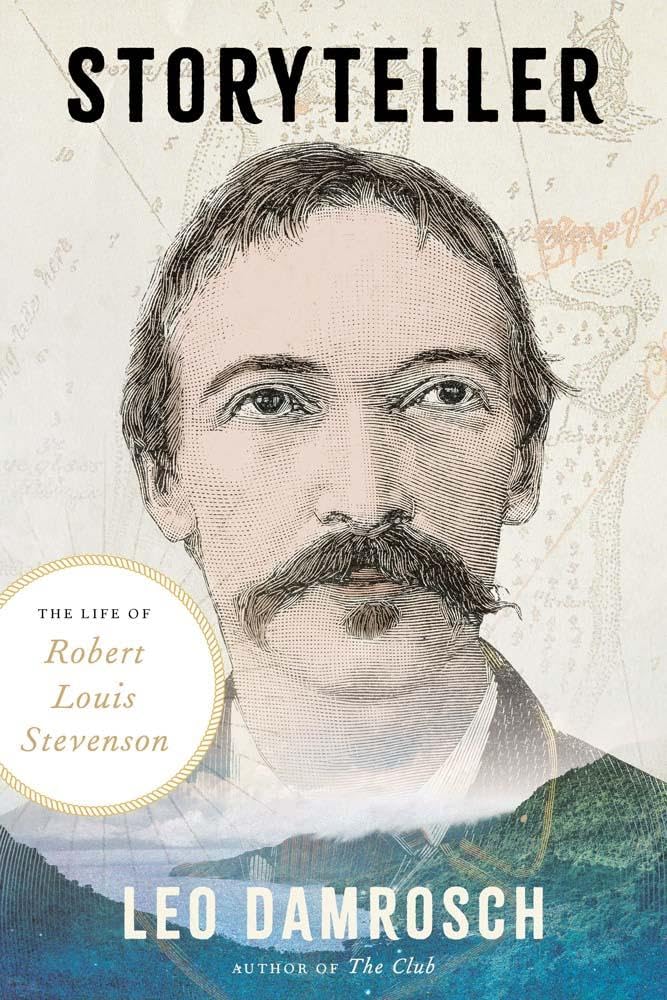

Storyteller:

The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson

by leo damrosch

yale university, 584 pages, $35

Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–94) belongs at the head of a select company of writers renowned in their day—Alexandre Dumas, Jules Verne, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle—who are no longer taken seriously, or for that matter read much, by most adults. However, the pleasures of reading adventure stories are not all guilty ones. The very best of such tales not only entertain but also teach—reminding grown men and women of fundamental truths they took in when young.

Stevenson relates swift-moving tales of high daring, with violent death narrowly averted by the herobut inescapable for the villains (and rendered with gruesome relish), profound male friendships forged in shared peril, and even the occasional—that is, really quite rare—first and only love for a young woman of exceptional mettle and bravery.

In 1924 the Bloomsbury stalwart Leonard Woolf confessed to finding Treasure Island “a good story,” but in his estimation it was plainly kid stuff: “[Stevenson] appeals to the child or to the primitively childish in grown men and women.” Not just childish, but primitively so. That hardly sounds like the distinguished achievement of a well-spent artistic career, or even a worthy pastime for the bookish reader seeking unfamiliar literary territory.

One is grateful, then, a century later, to see a scholar as accomplished as Leo Damrosch turn his attention to this neglected figure. Damrosch does not attempt to make more of Stevenson than he can legitimately bear, but this vivid biography helps one see what is essential in Stevenson’s life and perennially valuable in his art.

Raised in Scottish Presbyterianism, Stevenson was subjected to Calvinist doctrinal severity at its most frightful—as he would later call it, the “dark and vehement religion,” with its forbidding mystery of predestination, which kindled “the great fire of horror and terror . . . in the hearts of the Scottish people.” A “very religious boy,” in the words of his nanny, who schooled him only too well in the grim basics of her own fervent belief, the child confronted nightly a merciless ogre of a God who dominated his awful dreams and made him fear life as much as he did death. In his nightmare world he would stand before “the Great White Throne”—the seat of the Godhead administering judgment and vengeance in Revelation—and when ordered to speak in defense of his soul would be stricken mute, and thereby condemned forever to the burning pit, which he saw with staggering clarity before he woke up screaming.

At twenty-two, a graduate of Edinburgh University trained in Scottish law, and convalescent from a serious lung illness that would return to plague him all his life, in the course of an ordinary conversation Stevenson answered too candidly a couple of his father’s questions about his faith. The young man instantly regretted his forthrightness, as his parents pronounced him a “horrible atheist” (which he was not) and a loathsome disgrace who had rendered their lives meaningless: Better his son had never been born or had died a spotless babe, his father wailed. The reciprocal shock would reverberate for years, but the deathly parental rage would abate in time—they loved their son too much to banish him from their hearts. After Stevenson married in 1880 an American divorcée ten years older than he, his parents welcomed his strikingly unconventional wife into the family. By then relations had thawed sufficiently that Stevenson could write to his mother, with affection and without fear, of Christ’s habitual joyous “affirmatives” as against the solemn prohibitions of the Ten Commandments. “It is much more important to do right than not to do wrong. Faith is, not to believe the Bible, but to believe in God.”

It is obvious that Stevenson was never going to be an orthodox Christian of any denomination, but his early exposure to the divine “wrath and curse” visited upon fallen mankind, as the Scottish Presbyterian Shorter Catechism so memorably put it, and his growing belief in a loving Christ as the paragon of goodness, make themselves felt throughout his writings. His boyhood consciousness had been particularly seared by human depravity—principally the fear that his own would send him to hell—and his best-known works of fiction treat the eternal and elemental conflict between good and evil, as seen through the eyes of the innocent. At that time Nietzsche was declaring the Jewish and Christian standards of morality perverse and rightly obsolescent; Stevenson, by contrast, was reinforcing their inviolability, with an eye especially to the education of the young. Despite Stevenson’s renegade inclination to follow his own path, the uncharted territory that the atheist philosopher opened beyond good and evil was not for him.

Treasure Island portrays an adolescent’s initiation into the depths of manly wickedness—and his boldness in fighting against it. The sinister forces that generally flee the daylight penetrate the peaceable life of young Jim Hawkins. A succession of seafaring ruffians, each more rotten than the previous—Billy Bones, Black Dog, Blind Pew—arrive at his father’s inn, and bring with them terror and bloodshed, as they pursue the notorious pirate Captain Flint’s buried treasure. Pelf, loot, plunder: That is what pirates live and die for. But this fascination with riches infects the good men whom Jim knows, and with Flint’s treasure map in their possession a select group of them heads out to sea in quest of a fortune.

They are all innocents, with a lot to learn about the nature of evil. Squire Trelawney, the ringleader, unwittingly hires a crew of pirates who had sailed with Flint, among them Long John Silver, the peg-legged archvillain who has become the favorite buccaneer of popular legend. At first, they strike the Squire as virtuous men; but appearances can be fatefully deceiving, as Jim learns more quickly than his adult companions. Having climbed into a barrel on deck to get one of the few apples remaining there, Jim overhears Silver feverishly tell his fellow cutthroats of his plan to murder the good men—he imagines the most exquisite mutilations for the Squire—and take all the treasure for themselves. As Jim tells the story, “I would not have shown myself for all the world, but lay there, trembling and listening, in the extreme of fear and curiosity, for from these dozen words I understood that the lives of all the honest men aboard depended upon me alone.”

One lesson after another in maintaining his composure will follow. The pirates and the honest men will go to war, and several will be killed. Perhaps the biggest excitement comes when Jim fights to the death with the malignant Israel Hands. In a tour de force of practical criticism, Damrosch captures perfectly, sentence by sentence, the intricate and unrelenting narrative movement that renders the violent action, right down to the killing blow. This tribute to Stevenson’s artistry also demonstrates the excellence of old-school close reading, a relic of Harvard’s glory days, before leftist politics had its way with elite literary education.

A long 1888 essay by Stevenson’s good friend Henry James (a Harvard man, albeit as a law school dropout) represents an even older school of criticism at its best. James catches the psychic interplay between the adult reader and the young one, which makes this “boy’s book” unique: The “weary mind of experience,” fascinated by the story, will “see in it . . . not only the ideal fable but, as part and parcel of that, as it were, the young reader himself and his state of mind: we seem to read it over his shoulder, with an arm around his neck.” Bloomsbury’s contempt for Stevenson’s primitive childishness seems fusty and churlish in light of this far subtler and more humane understanding. James recognizes the love this novel inspires the old to feel for the young—the protective tenderness for a soul yet unformed as it finds its difficult way through the thickets of the moral life.

And for all that, it is a ripping good yarn, like Stevenson’s other most remarkable works of fiction. Each of these is singular in plot, but all are similar in their fundamental teaching: that righteous men must resist wrongdoers with all the courage they have, especially when the vicious have superior strength.

In Kidnapped (1886), seventeen-year-old David Balfour, another slow learner, narrowly escapes a murderous pitfall contrived by his malicious miserly uncle Ebenezer—yet still trusts the old reprobate enough to be suckered aboard a ship manned by evildoers, whom Ebenezer has paid to transport him into indentured servitude in the Carolinas. David, too, will have to fight for his life, and is fortunate to have at his side an expert swordsman who will become his fast friend.

In The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (also 1886), the scientific genius Dr. Jekyll’s experiment in the ecstatic release of the evil in his own being rings the death knell for Victorian hopes of moral perfectibility: Human wickedness is profound and ineradicable, and it will always have to be fought.

And in The Master of Ballantrae (1889), James Durie, the titular villain, Stevenson was to say, embodies “all I know of the devil.” Charming, handsome, dashing, clever, he is the epitome of diabolical grace—the finest worldly gifts put to the foulest use, as he sows devastation wherever he goes. No one stands successfully against him.

Lest it appear that Stevenson was a cheerless scold, a font of unresolved Calvinist wretchedness, a look at some of his best essays dispels that supposition. (It is as an essayist—a brilliant and prolific one, as shown by a 2024 edition of his Complete Personal Essays, which is more than seven hundred pages long—that he currently enjoys a greater reputation than as a novelist. He does not write for boys here.) “Fontainebleau: Village Communities of Painters” identifies joyous pleasure as the root of all the best things. “No art, it may be said, was ever perfect, and not many noble, that has not been mirthfully conceived. And no man, it may be added, was ever anything but a wet blanket and a cross to his companions who boasted not a copious spirit of enjoyment.” “Pulvis et Umbra,” despite its dour title—Dust and Shadow, taken from a Horatian ode—and its reckoning with the shortcomings of religion on one hand and science on the other, closes with an energetic flourish of virile determination: “God forbid it should be man that wearies in well-doing, that despairs of unrewarded effort, or utters the language of complaint. Let it be enough for faith, that the whole creation groans in mortal frailty, strives with unconquerable constancy: Surely not all in vain.” It is a memorable summons to the morally rigorous life.