Secretary of War Pete Hegseth announced that he is revamping the U.S. military’s chaplain corps as part of his broader reform efforts, and he’s taking aim at what he terms the “new age” tendencies that have metastasized in the corps. The military’s chaplains, Hegseth declared in a video statement, “are chaplains, not emotional support officers, and we’re going to treat them as such.” Hegseth’s remarks will almost inevitably be treated as evidence of creeping theocracy or Christian nationalism, and by the standards of twenty-first-century liberal America, it might be. But Hegseth’s new chaplaincy is not a renegotiation of the relationship between religion and the regime. Religion and religious actors have been serving the deeply political purposes of the American republic since 1776.

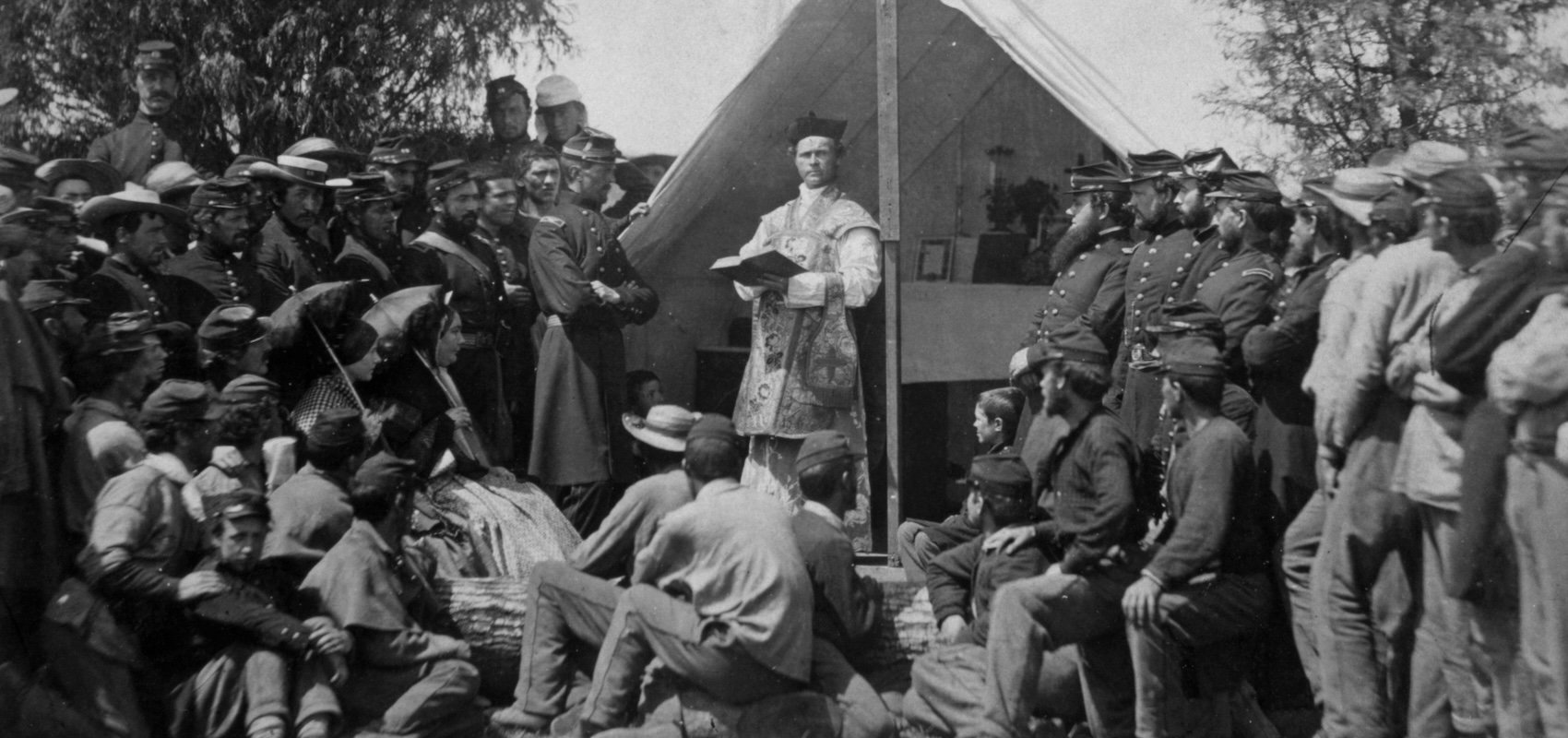

From the American Revolution, to the Civil War, to the fight against fascism in the Second World War, to the Cold War against communism, to the Global War on Islamist terror, the United States has demanded clerics in military service to uphold the political aims of the republic. Hegseth’s changes are, in fact, nothing more than the present government asking the chaplain corps to fulfill the same mission it has been charged with since the American Revolution: giving spiritual and religious affirmation to men pursuing political aims. In that sense, the chaplain corps of the American republic has always been political, and it must answer to political actors, including the Secretary of War.

Hegseth is a communicant in good standing of the Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches (CREC), a Reformed Protestant denomination that rejects the spiritualist and individualist religiosity of twentieth-century fundamentalism and evangelicalism, and the theological heterodoxies of the mainline. The CREC extols natural and political hierarchy, traditional gender roles, and has a robust place for political theology in its preaching and catechetical material. For Hegseth—and indeed for most of the history of the Christian Church and Western governments—politics, Christianity, and war are all connected.

The recognition that religion and religiously-influenced political virtue plays a role in warfighting is not necessarily a spiritual observation. Hegseth seems to think, with good reason, that healthy military policy makes religion necessary for supporting and strengthening the American fighting man. Hegseth ordered a “top-down cultural shift, putting spiritual well-being on the same footing as mental and physical health.” This, he argued, was a “first step toward creating a supportive environment for our warriors and their souls.” The implication is that whatever type of religion that has been offered by the chaplain corps in the recent past has not been supporting American warriors.

Hegseth decried how chaplains were intended to be the spiritual and moral backbone of the armed forces, but in recent decades, “faith and virtue were traded for self-help and self-care.” “Chaplains,” he said, “have been minimized, viewed by many as therapists instead of ministers.” Hegseth scoffed at the army’s spiritual fitness guide, which mentioned God one time, but mentioned “feelings” and “playfulness” regularly. The army’s spiritual guide “relies on ‘new age’ notions, saying the soldier’s spirit consists of consciousness, creativity, and connection . . . yet ironically, it alienates our warfighters of faith by pushing secular humanism. In short, it’s unacceptable and unserious. So we’re tossing it.”

The War Secretary is tossing more than the army’s paper description of chaplains. He is tossing nearly a century of fundamentalist evangelical spiritualism and mainline liberalism. Hegseth wants to “restore the esteemed position of chaplains as moral anchors for our fighting force.” The army’s 1956 Chaplain’s Manual stated that, “The chaplain is the pastor and the shepherd of the souls entrusted to his care.” The revival of the chaplaincy as “a high and sacred calling” is Hegseth’s goal, but he admitted that his plan only works “if our shepherds are actually given the freedom to boldly guide and care for their flock.”

The restoration of chaplains as moral guides and teachers restores the American republic’s reasons for creating chaplains in the first place. While their vocation as spiritual counselors is valuable, the American republic historically asked chaplains to teach its soldiers and sailors the moral and religious values of the republic. In the nineteenth century that morality and civic religion was Protestant. By the twentieth century it had broadened to include Jews and Roman Catholics under the rubric of Judeo-Christian. Hegseth seems less interested in fighting confessional battles within the Judeo-Christian settlement and more interested in making it clear that the American military is neither value-neutral, nor dedicated to an open-ended socio-moral telos.

There are implied religious commitments that make America’s fighting men stronger—Judeo-Christian ethics—and there are ones that do not. Hegseth is more explicit about the latter; he doesn’t like new age beliefs, or secular humanism. Hegseth, like all of his predecessors, is drawing lines and picking horses. Secular multiculturalism is out; Judeo-Christian belief is back in, and it’s got the backing of the state.

Just War Theory and Epic Fury

The machines of war have sprung into action once again in the Middle East. Bombs are falling…

What the USCCB Gets Wrong About Birthright Citizenship

In the wake of the 2007 Supreme Court decision to uphold Kansas’s ban on partial birth abortion,…

Politics of the Professoriate (ft. John Tomasi)

In the latest installment of the ongoing interview series with contributing editor Mark Bauerlein, John Tomasi joins…