The great essayist William Hazlitt observed that there is pleasure in hating. “Without something to hate,” he wrote, “we should lose the very spring of thought and action.” But I think there is equal or greater pleasure in admiring. Our culture doesn’t generally value admiration. We’re constantly encouraged to promote ourselves, create a personal brand, and “self-optimize.” What if we instead turned the inward eye outward, upon all that the world offers for our admiration?

When we admire, we are freed from thoughts of ourselves. The better we are at admiring, the less our egos intrude. And the more we know about the world, the more we find to admire. We can then look with pleasure not only on natural and human beauty, but also on more complex things, such as painting, poetry, philosophy, even moral conduct. The excellence of particular human beings is often the most affecting beauty of all.

I love to watch others at their best: the brilliant philosopher at work, the pianist who makes playing look effortless, the mother who patiently handles constant requests for her attention. I want to be like these people, unlikely as that may be. “Whatever is done skillfully,” wrote Samuel Johnson, “appears to be done with ease; and art, when it is once matured to habit, vanishes from observation. We are therefore more powerfully excited to emulation, by those who have attained the highest degree of excellence, and whom we can therefore with least reason hope to equal.”

Admiration is countercultural, especially in the academy. We are taught to be “critical” thinkers—always finding fault, identifying problems, exposing deficiencies. The academy is obsessed with status and ranking: Do professors publish in top-tier journals? Can our institutions keep up with their “aspirant peers”? It’s certainly true that most people are inclined to take pleasure in the faults of others. As Hazlitt observed, failure is consoling: At least I’m not as badly off as that guy. Insecurity and pride combine in judgments such as these.

I think, though, that it’s more valuable to admire. Everyone wants to be seen and understood; paying attention is a kind of care for another person. Learning to appreciate beauty and excellence is also the essence of liberal education. A liberal education isn’t so much character-building, but a cultivation of the receptive consciousness, a disposition of appreciation.

Admiration calls for at least three things. The first is candid self-examination. What talents and inclinations do I possess, and how might they be developed? I may be forced to admit, in my mental and moral stocktaking, that I’m not good at very many things, or that other people are more gifted than I. Others may have better memories, a subtler grasp of philosophical argument, greater insight into literature and life. I must tell myself the truth about these matters, and only then turn to admiration. Otherwise, the excellence of others feels like a threat.

This truth-telling isn’t all darkness and failure. It may become pleasanter as we age, for in taking stock of ourselves we mark our successes, too. Many human capacities can be changed, developed, perfected through effort.

This brings us to a second quality that is necessary for admiring well: Admiration requires us to become connoisseurs of a sort. Connoisseurship—whether of wine, art, movies, pop music, or a thousand other things—doesn’t emerge all at once. Becoming a master sommelier, for example, takes at least five years of intensive training, and usually many more. Sometimes connoisseurship comes unbidden. After eight years of living with one breed of dog, I immediately recognize its distinctive ways of jumping and running when I see the breed on the street. I can’t quite articulate it, but I know it when I see it. Something like this half-conscious expertise must characterize the highest levels of literary or artistic criticism, though to reach those levels would take a lifetime.

I recently became friends with the owner and curator of an art gallery. Alan is not a visual artist, but he is a gifted connoisseur—an admirer of other people and the works they produce. He has a finely honed vision of artistic excellence and a capacity to judge quality. Sometimes he will position a monotonal abstract painting next to a vibrant, colorful landscape, for contrast. Or he’ll group a set of works in some unexpected way. Or he might display a piece alone, starkly, on a white wall. The gallery is itself a work of art, which, to borrow words from Adam Smith, exemplifies “the acute and delicate discernment of the man of taste, who distinguishes the minute, and scarce perceptible differences of beauty and deformity.”

Alan admires his artists, and I admire his gallery. Admiration requires a degree of mutual understanding, a common standard of value, a sense that I can judge the quality of what I see, hear, or read. Understanding is the more necessary because many objects of admiration don’t reside on the surface of life. Physical beauty is easy enough to see, though it won’t be seen the same way by everyone—and thank goodness, or it would be bad news for the perpetuation of the human race. But admiration of another person’s intellect or character requires connoisseurship. It is a “coming to know” what is valuable, a seeing how a person embodies artistic excellence, or kindness, or humility, or any other good or beautiful quality. It constitutes the very pleasant task of becoming educated, in multiple realms of experience.

At least one more characteristic is essential for the admirer: a recognition of fallibility—both our own and that of others. If we are waiting for perfection, then we will find nobody at all to admire. I have noticed that my admiration of other people isn’t blind; it usually coexists with an awareness of imperfections, flaws, and deficiencies. I can observe a person’s brilliance while knowing that he is short-tempered and prone to criticism, or perceive that a friend is insightful in politics but tone-deaf to literature, or vice versa. This disposition may be indulgent, but it isn’t naive.

In the same way, if we wait for our own insecurities to disappear, then we’ll never be able to admire anyone. Excessive self-criticism is devastating for our sense of ourselves; it also prevents us from looking up to see the people around us. We coil ourselves up into balls of anxiety.

Many things are worthy of admiration, from art to literature to athletic excellence. But lately I’ve come to think that the most admirable qualities of all are excellences of character: the kindness, humility, piety, humor, and genuine goodness of people who may not be intellectually or artistically sophisticated. These people often go unadmired because they are not interested in—indeed, have never given a moment’s thought to—their public image. They aren’t engaged in the kinds of things that garner widespread approval or praise.

Instead they are taking care of the church, cleaning up the service leaflets that accumulate at the end of Sunday services, or making the coffee early every morning. They are investing in the lives of others, quietly and unobtrusively. They talk and listen. They are introspective and extroverted by turns, but they possess a generosity of spirit that everyone can admire, if only we will open our eyes. The man of perfect virtue, wrote Smith, “the man whom we naturally love and revere the most, is he who joins, to the most perfect command of his own original and selfish feelings, the most exquisite sensibility both to the original and sympathetic feelings of others.”

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle notes that the great-souled or magnanimous man is “not given to admiration because nothing is great to him.” In other words, only less-than-great souls admire others. But how lonely this exalted position would be! A person who is so gifted or highly placed that he cannot admire others is missing out on one of life’s great pleasures: the self-forgetfulness of wonder and admiration, which may sometimes lead toward a profound Christian caritas.

In America we’re told that independence, self-sufficiency, and dogged hard work are among the greatest virtues. I would much prefer to throw in my lot with the admirers. Openness to the beauty of the world, and to the people around me, means that I can be receptive to the unmerited grace that may sometimes, surprisingly, appear. When it does, it is a great blessing—something not to be missed.

The Testament of Ann Lee Shakes with Conviction

The Shaker name looms large in America’s material history. The Metropolitan Museum of Art hosts an entire…

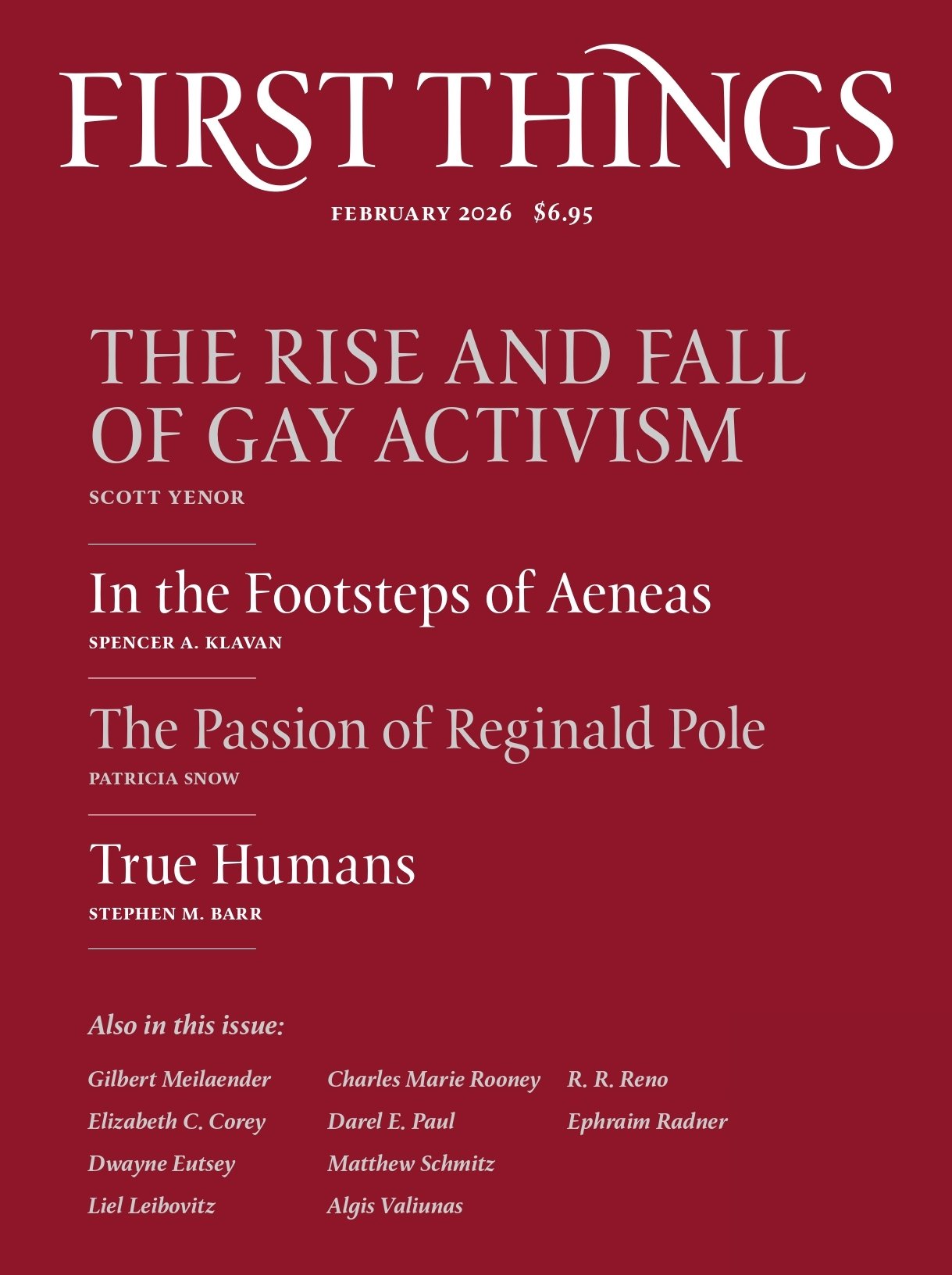

What Virgil Teaches America (ft. Spencer Klavan)

In this episode, Spencer A. Klavan joins R. R. Reno on The Editor’s Desk to talk about…

“Wuthering Heights” Is for the TikTok Generation

Director Emerald Fennell knows how to tap into a zeitgeist. Her 2020 film Promising Young Woman captured…