What are rituals?

Rituals are not just routines. Mere routines are pragmatic and instrumental. Rituals transcend routines when they are endowed with special meaning and aesthetic depth. Rituals are unlike practical concerns in that everyone must be given a role to play. This unconditional quality mirrors the absolute bonds of family.

Rituals assert a break from conventional existence. In so doing, they stand out and become memorable. The transition from mundane to sacred is felt strongly in rituals: the night before Christmas, the joining of hands before grace, the lights turned off before the birthday candles are lit, the imposition of ashes on Ash Wednesday.

Rituals assert, “this is who we are.” In their repetition, they convey stability, structure, belonging, and a sense of “rightness.” They define a boundary between correct and incorrect, between family and outsider.

Philosopher Byung-Chul Han has noted that, while houses are homes in space, rituals are homes in time. Han draws from the perspective of French aristocrat Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who wrote in The Wisdom of the Sands:

And our immemorial rites are in Time what the dwelling is in Space. For it is well that the years should not seem to wear us away and disperse us like a handful of sand; rather they should fulfill us. It is meet that Time should be a building-up. Thus I go from one feast day to another, from anniversary to anniversary, from harvestide to harvestide as, when a child, I made my way from the Hall of Council to the rest room within my father’s palace, where every footstep had a meaning.

The space that rituals create to pass on myths facilitates “identity integration”—the reconciling of different parts of the self, the generations, and the family into a greater whole. Rituals are an assertion of continuity.

They have a deep protective value. They are familiar, reliable, habitable; we can sink into them, forgetting for a moment our personal vulnerability.

The medical and sociological literature abounds with examples of ritual as a source of strength: The children of alcoholics who maintain family rituals are less likely to become alcoholics themselves, and asthmatic children from “ritual-protected families” are better able to stabilize themselves in challenging situations.

Conversely, the absence of family rituals is highly destructive to family well-being, as Sarah Ban Breathnach observed in her essay “Tradition, The Tie That Defines”:

One of the most powerful findings that emerged from observation studies in families with disturbed children “was that these families didn’t seem to set aside anything as special. They didn’t try to build traditions. Mealtimes were mundane. Bedtimes were boring. Leaving the house and coming back was completely without spirit. The absence of traditions and rituals in these families was giving the children the message that they weren’t important and that the family wasn’t important.”

As we write ourselves into these rituals, so they write themselves into us. The values that they represent are embodied as we adopt them and act them out. Han writes: “They are written into the body, incorporated, that is, physically internalized. Thus, rituals create a bodily knowledge and memory, an embodied identity, a bodily connection.”

The establishment of family rituals is essential for perpetuating a virtuous family across time and generations. The wealthy always lead lives of exceptional temptation, given the ease with which they can indulge lust, gluttony, and sloth. School and extracurricular activities for children must therefore be prioritized—those that teach iron discipline. Physical challenges have an essential role to play here, and always have since the nobility’s inception.

Consider the metaphysical framework that underpinned jousts and other aristocratic combat tournaments. These emphasized the cultivation of the virtue of hardiness—to be tough and undaunted, in body as in spirit. As historian David Crouch explains in The Birth of Nobility:

Geoffrey de Charny also emphasised the masculine admirability of hardiness, but interpreted it more broadly in the light of the religious feeling of the contemptus mundi. . . . They should endure cold and heat with equal indifference; they should care little for the fear of death; they should strive hard and ignore discomfort and wounds. . . . For him, the body is of little consequence in the face of the honour that an undaunted spirit can earn.

The first and central virtue to be gained through the authentic pursuit of sport is the discipline to joyfully embrace hardship and pain. The child who masters his body against sloth, gluttony, and cowardice is well disposed to later master his spirit against lust, avarice, and corruption. There is no noble spiritual system that does not require this strength. This mastery of self fundamentally underpins the pursuit of all higher goals.

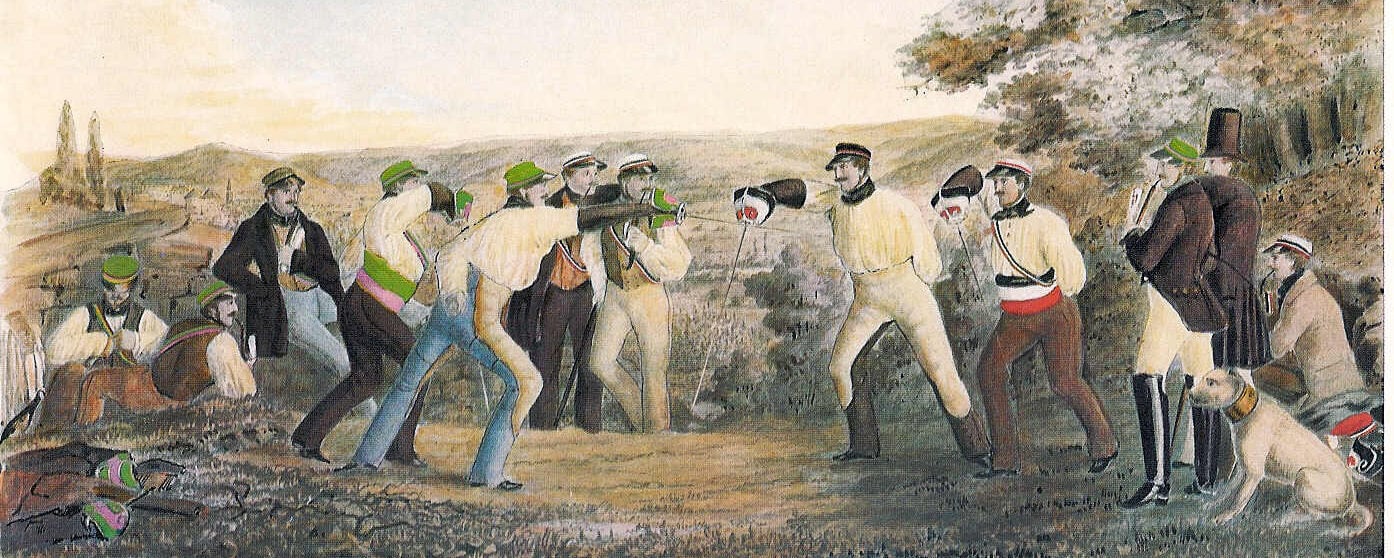

As such, every upper caste has a noble and dangerous sport—hunting boars, racing across the polo field—even ritualized dueling in the aristocratic practice of mensur at elite German universities. Within the parameters of the strict rules of mensur, danger remained—scars were common—and this taught courage, steadfastness, and will.

Many of these historic practices now strike us as extreme. Older times were perhaps more familiar with danger and death than we are now. But within the bounds of modern acceptability, sports, danger, and discomfort should be a part of every child’s upbringing. Explore climbing, riding, hunting, swimming, rugby, polo: whatever is available.

A familiarity with real risk is necessary. The aristocracy have always engaged in dangerous games. This familiarity with death—memento mori—reminds us of the shortness of life, the greatness of the stakes, and the close proximity of the next life. Dangerous games are less about victory over the opponent, and instead force a focus on victory over the self.

This essay is an adapted excerpt from Johann Kurtz’s recently published book, Leaving a Legacy: Inheritance, Charity, & Thousand-Year Families.