A Defense of Free Will Against Luther:

Assertionis Lutheranae Confutatio, Article 36

by st. john fisher, translated by thomas p. scheck

catholic university of america, 324 pages, $75

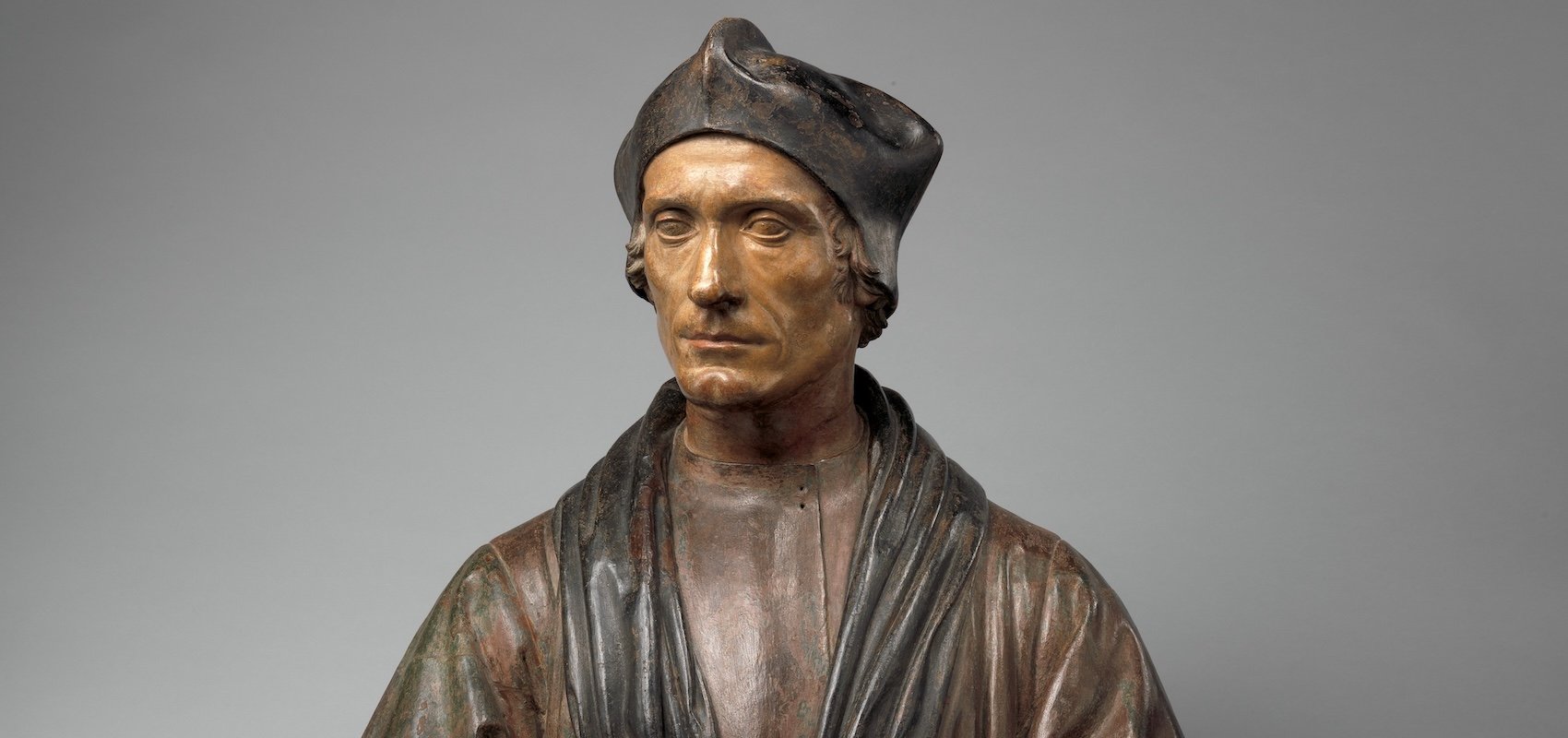

John Fisher, the renowned Bishop of Rochester, is known to history chiefly for having been put to death by King Henry VIII in 1535 for the “treason” of denying that Henry was “the only supreme head in earth of the Church of England.” In his own lifetime, however, Fisher had achieved European fame as one of the most influential early opponents of Martin Luther—a role into which he had been led by the example of none other than his king. Thomas P. Scheck has put English-speaking readers in his debt with this translation of two key sections of the most significant book Fisher published, his Assertionis Lutheranae Confutatio (Confutation of Luther’s Assertion).

This text, which first appeared in January 1523, aimed to refute Luther’s defense of his 41 theological statements that Pope Leo X had condemned in the 1520 bull Exsurge Domine. The Confutation was a fairly comprehensive attack on Luther’s system, even though the condemned articles did not include either of Luther’s two fundamental doctrinal principles—justification by faith alone and the dogmatic authority of Scripture alone. Fisher addressed this lack by prefacing his work with a couple of essays identifying and engaging with those two principles.

The analysis of Lutheranism as a system founded on the two basic doctrines of “faith alone” and “Scripture alone” is still a commonplace of textbooks, and Fisher was one of the first to present it. He originally offered this analysis in a sermon to the citizens of London at St. Paul’s Cathedral on May 12, 1521, when the papal condemnation of Luther was promulgated in England and when it was announced that the king himself had written a book against Luther. Henry’s decision put the kingdom of England at the forefront of the Catholic response to Luther for almost a decade. The “U-turn” that was to set the king against the papacy by the early 1530s would have been unimaginable at that moment.

Scheck’s translation offers English renderings of the first of Fisher’s prefatory essays, the one on the principle of “scripture alone,” together with the longest of his responses to Luther’s individual articles—Article 36, on free will. Fisher’s Confutation was widely read in its time, running to about 20 editions by 1600, many of them published in the 1520s, and it left its mark on the Catholic response to what would come to be called “the Reformation.” It was often cited or invoked at the Council of Trent in the middle of the century, its reputation enhanced by its author’s status as one of the first Catholic martyrs of the English Reformation. Article 36 was especially important. Free will was, famously, the issue over which the great Christian humanist scholar, Desiderius Erasmus, began to sever his ties with the Reformation, despite his initial sympathy with the concerns and goals of the reformers who came to be known as Protestants. Erasmus’s Diatribe on Free Will (1524) showed that he could not accompany them on their new path. Notwithstanding its title, the Diatribe was a measured and polite engagement with Luther’s teaching (the word diatribe, directly imported from the Greek, only acquired the pejorative sense of “rant” centuries later). As Scheck emphasizes in his substantial introduction to this volume, it has long been acknowledged that Erasmus was heavily indebted to Fisher’s treatment of this topic, and it may well have been Fisher’s work that alerted him to the crucial role free will played in Luther’s theological system.

Erasmus entered the lists against Luther because he was put under considerable pressure to do so, not least by English friends and patrons who were very important to him. For the most part, the things he wrote were things he freely chose to write, in pursuit of his own intellectual goals and aspirations. Publishing books, together, perhaps, with writing letters, was what defined him as a person. He was a man of letters. By contrast, Fisher wrote against Luther because it was his duty to do so. Everything Fisher published (as well as most of the things he wrote that remained unprinted) was the fulfillment of some very definite duty. Thus his Sermons on the Seven Penitential Psalms (1508) were preached and published at the behest of Lady Margaret Beaufort (mother of Henry VII), whom he served as what we would call a spiritual director. His funeral sermon for Henry VII and his memorial sermon for Lady Margaret were evidently court commissions. And his sermon at the burning of Luther’s books in 1521 was presumably delivered at the command of Henry VIII or Cardinal Wolsey, or both, since they had planned the entire occasion. Fisher made clear that his Confutation of Luther’s Assertion, like all his efforts in polemical theology, was written in pursuance of his duty as a bishop to defend the souls entrusted to his care from the snares of heresy. If Erasmus’s identity was essentially authorial, Fisher’s was above all pastoral.

Fisher took great pains, for example, to urge repentance on the unknown miscreant who had scrawled some graffiti on a papal bull (the source for this episode says it was an indulgence) that had been posted on the door of Great St. Mary’s, the university church in Cambridge. He addressed the university assembly on three separate occasions in his capacity as its chancellor, but the culprit kept quiet. He was much later identified as a Frenchman, Pierre de Valence, who went on to spend some years in the service of Henry VIII’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, and to commit himself wholeheartedly to the Reformation.

The progress of Lutheran and other heretical doctrines at Fisher’s beloved alma mater caused him increasing grief over the next ten years. In February 1526 he preached another sermon at Paul’s Cross, this time at the first public recantation of the newfangled dissidents in England. Most of those disavowing heretical beliefs on that occasion were German merchants from the “Steelyard” (the Hanseatic trading station in London), whom Thomas More had found in possession of Lutheran books during a spot search. But with them was Dr. Robert Barnes, who had preached a sermon modeled on one of Luther’s at the little church of St. Edward’s, just off the market square in Cambridge, on Christmas Eve 1525. This airing of Lutheran ideas by a member of the Cambridge Divinity Faculty must have seemed to Fisher an almost personal betrayal. Publishing his sermon soon afterward, he explained: “My duty is after my poor power to resist these heretics, the which cease not to subvert the church of Christ.”

He went on to invite anyone unpersuaded by the arguments of his sermon to come to him confidentially so that they could thrash matters out for as long as it took for the doubter to “make me a Lutheran” or for Fisher to “induce him to be a Catholic.” There is no reason to think anyone ever took up that offer, with its naive confidence in the power of debate to resolve disagreements.

Barnes himself appeared several times before a panel of bishops (including Fisher), but although he abjured at St. Paul’s, he certainly wasn’t won over. Within a few years he had fled the country to join Luther at Wittenberg, and many years later he would die a martyr’s death at Smithfield on account of his outspoken Lutheranism, though in political terms his execution was collateral damage from the fall of Thomas Cromwell in 1540.

Fisher’s arguments against Luther were often pithy and at times irrefragable, as in his version of one of the most obvious rebuttals of the exclusion of “works” from the process of justification, presented in his 1526 sermon. Taking up one of Luther’s favorite proof texts for this theory, Jesus’s assurance that “your faith has saved you” (Luke 7:50), Fisher wrote:

Our Saviour saith, not only Fides, but Fides tua. Thy faith (a truth it is) is the gift of God. But it is not made my faith, nor thy faith, nor his faith, as I said before, but by our assent. . . . But our assent is plainly our work. Wherefore at the least one work of ours joineth with faith to our justifying.

Logic, however, usually loses out when passions are engaged, and Kołakowski’s Law of the Infinite Cornucopia reminds us that there is an endless supply of arguments that can be deployed against this elegant rebuttal. But they do not leave it any the worse for wear, and so they only confirm that scriptural interpretation can never be the plain and simple thing that Luther said.

Fisher himself was perhaps too close to the action to decipher the full significance of what was unfolding around him. Thomas More saw a little further into it and into the future, warning his son-in-law William Roper even in the 1520s, when England’s Catholicism seemed so secure under royal patronage, that there might come a time—it came far sooner than he imagined—when Catholics would be happy to let the heretics “have their churches quietly to themselves” as long as “they would be content to let us have ours quietly to ourselves.” The essence of what Luther was about was the quest for a personal certainty of salvation (“assurance,” as it came to be termed by its exponents). And for him, reasonably enough, the intrinsic sinfulness of human nature meant that salvation could not be certain if it depended to any degree on human operation or cooperation. In the words of another of his favorite biblical tags, omnis homo mendax (“all men are liars,” Ps. 116:11). Only God was true. So faith had to justify “alone,” as God’s pure gift, without any operation or even cooperation on the part of the believer. And Scripture had to instruct “alone,” as a totally transparent text, without any interpretation by any human agent or intermediary—whether the believer himself, a priest, or the church as a whole.

To a scholar such as Fisher, who had imbibed at Cambridge the theological traditions of the via antiqua—the “old way” of Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus—Luther’s cavalier dismissal of most of the sacraments, together with his via moderna (“new way”) emphasis on the sheer will—one might almost say the sheer willfulness—of God, was always likely to be rebarbative. On the subject of scholastic theology, by the way, Scheck advances in this book, as he has done elsewhere, a case for seeing Fisher as a Scotist. It remains my own view that Fisher was more an eclectic than a disciple of any specific figure, but that nonetheless he had a particular predilection for Thomas Aquinas, whom he more than once acclaimed as “the flower of theologians.” Yet whatever might be thought of his precise theological affiliation, his theological center of gravity lay firmly within the “realism” of the High Middle Ages rather than the “nominalism” of the Later Middle Ages.

Luther’s doctrine of the transparent text, that alluring fancy, had a profound effect on English and even more on American (that is, U.S.) culture, formed and shaped as it was from the start by Protestantism. The American commitment, or rather fidelity, to the Constitution has not unreasonably been traced to that respect for the Bible that underpinned American culture until within living memory. The analogy, however, is more revealing than is often appreciated by those who draw it. The Constitution is, as texts go, coherent, and it was written with clarity in mind. Yet it cannot function alone. You cannot appeal simply to the Constitution. You have to appeal to that other SCOTUS, whose interpretative authority far exceeds any ever ascribed to Scotus. Without those nine supreme pontiffs, even this simplest and most transparent of texts is nothing more than a piece of paper.

Luther’s specious notion of the self-interpreting or transparent text burst upon a world in which “the Bible” was being made much more real and accessible by the technological miracle of the printing press, in a potent coincidence that greatly enhanced its plausibility. But the limitless doctrinal fragmentation that was already evident by 1530 amply vindicated the observation of early Catholic polemicists such as Fisher and More that “Scripture alone” made every man his own pope. The Protestant world started by decrying this conclusion as a calumny but by 1700 often treated it as a dogma, under the label “private judgment.”

The tragedy was that this early sixteenth-century moment, the moment of print, the moment of the “three languages” (Latin, Greek, and Hebrew), the moment that briefly spoke through Erasmus and, among other effects, inspired John Fisher to diversify the curriculum at Cambridge by introducing both Hebrew and Greek, was poised to herald a new era in scriptural scholarship. As it happened, this new era was one of bitter confessional strife, thanks to Luther’s relentless and egotistical insistence on absolute assent to whatever he happened to decide was the plain meaning of Scripture. The Scottish humanist Florentius Volusenus later told the story of a conversation at Rochester, probably around 1530, in the course of which Fisher admitted to him that he wondered what divine providence meant by making some Lutherans such fruitful commentators on Scripture despite their being heretics. Even Fisher, it seems, was impressed by their scholarship. Even he felt the pull of Luther’s evangelical summons to unquestioning faith in Jesus’s promises, as Volusenus later emphasized in the same book (De Animi Tranquillitate Dialogus). Yet Luther’s evangelical rhetoric did not persuade Fisher, as it persuaded so many, to subscribe to his logical absurdities or theological foibles.

Luther’s theology, notoriously, is heavily based in the Latin tradition and the Vulgate text. For all his grappling with the Hebrew and the Greek, his theological vocabulary is the legacy of late scholasticism, and Erasmus took the measure of him pretty fairly in his Diatribe, identifying him as just one more needlessly dogmatic scholastic. Although the Christian humanist program of Erasmus did nothing so crude as to reduce the Bible to the level of a human text, it did seek deeper understanding of the Scriptures by treating them, in many respects, like any other human text. Luther’s approach was, at the theoretical level, exactly the opposite. It was to treat the Bible as entirely different from any other human text, because of his overwhelming need to deliver human salvation from anything that made it contingent on merely human causes. This emphatically anti-humanist approach explains why the phrase “Word of God” took off so strongly among Luther’s followers and, ultimately, among all Protestants as a name for the Bible. It was about emphasizing the difference. This is not to say that humanist critical approaches were eschewed by Protestant exegetes. Far from it. Many highly skilled humanist scholars were persuaded by the teachings of the Reformers, and they applied their skills to the teaching and understanding of the “new learning” that Luther had brought to light and to the understanding of the Scriptures. It was doubtless some of those efforts that so impressed John Fisher.

Thomas P. Scheck’s translation is careful and faithful, and his introduction full, informative, and illuminating, even if there are one or two fine points of interpretation on which I might beg to differ. There is one error, however, that cannot pass without correction, because it goes to the heart of the issue for which John Fisher was to give his life. Scheck rightly notes that, as J. J. Scarisbrick showed nearly forty years ago, Fisher actually entered into discussions with the Emperor Charles V’s ambassador to Henry’s court, Eustace Chapuys, about the possibility of imperial intervention to correct the English king as he became increasingly opposed to the pope. However, Scheck’s elaboration, that “this secretive endeavor was exposed, and Fisher was arrested,” has no basis in the historical record and must be rejected, together with the implication that Fisher’s intervention explains his execution, which took place more than a year after his arrest. Henry’s regime never heard so much as a whisper of Fisher’s discussions with Chapuys, and had they done so Fisher would have been for the chop in a month, not a year. Those who actually conspired against Henry got very short shrift. Fisher’s dealings with Chapuys would indubitably have been deemed treasonous had they come to light at the time. But they did not. To that extent, it seems, the bishop was as adept at secret communication as at most other things he turned his hand to.

Fisher was arrested in April 1534 because he refused to take the Oath of Succession. More than a year later, he was executed because, in the words of the indictment,

on 7 May 1535, in the Tower of London in the County of Middlesex, [he] did, contrary to his due allegiance, falsely, maliciously and traitorously utter and pronounce the following English words, namely, “The king our sovereign lord is not supreme head in earth of the Church of England.”

It all took so long for two reasons. First, the regime had to enact new laws to criminalize Fisher’s position. The Act of Supremacy and the Treason Act were therefore passed during the winter of 1534–35. More importantly, though, the king wanted submission, not sacrifice. He wanted John Fisher, like Thomas More, to agree with him, or at least to acquiesce in his will. So they were given plenty of time to weigh an inevitable punishment against the mere words necessary to save their skins.

Henry would far rather have had their acquiescence than their blood; indeed, there were probably no men whose approval he craved so desperately. Thomas More had been his secretary and companion at court in happier times, with an international reputation as a scholar and Latinist thanks to his Utopia. As chancellor, he had zealously implemented Henry’s determined policy of censorship, propaganda, and repression against English heretics. Fisher had never been a courtier, and he was an austere, somewhat forbidding figure, of whom it was once said, “not only of his equals, but even of his superiors, he was both honoured and feared.” But in the heyday of the campaign against Luther in the early 1520s, he was in the highest favor with the king. On his way back from Canterbury to London in June 1522, Henry had called to see the bishop at Rochester and it was reported that “the king called on my lord as soon as he were come to his lodging, and he talked lovingly with my lord all the way between the palace and his chamber in the abbey.”

Henry’s piety was always oriented to the Book of Psalms, and at some point in the mid-1520s he commissioned from Fisher a full-scale devotional commentary on the Psalms. The commentary still survives, unfinished and fragmentary, in various working drafts, obviously set aside by the bishop when he was drawn into defending the validity of Henry’s first marriage, to Catherine of Aragon, the task that made his former friend an enemy. That the two best known scholars in his kingdom would neither of them publicly endorse his divorce and his break with Rome was a rebuke the king could not bear. It remains the most revealing judgment on the events that started that very peculiar thing, the English Reformation.

The Serpent and the Dove

Late in the evening of Thursday, September 8, 1955, Communist Party officials in Shanghai launched a mass…

Students for Notre Dame

As I walked out of class Thursday morning, the day before the planned student-led “March on the…

What the USCCB Gets Wrong About Birthright Citizenship

In the wake of the 2007 Supreme Court decision to uphold Kansas’s ban on partial birth abortion,…