Earlier this summer, Egypt’s Ministry of Religious Endowments launched a new campaign. It is entitled “Correct Your Concepts,” and you need exert little effort to figure out which perceptions the government deems in need of correcting. Online ads and videos, designed to appeal even to the youngest of viewers, explain it all in the simplest terms imaginable. One ad, for example, shows a young man smiling beatifically while feeding stray cats in the streets, followed by another man frowning menacingly while attempting to pummel a cat with a stick. The first is adorned with a green checkmark; the second with a big, red X.

Joining animal cruelty in the campaign’s list of discouraged behaviors is smoking, vaping, cheating on tests, consuming online pornography, spending too much time on social media, beating children, and wasting water. It’s an extensive list, and the government informed its subjects that the stakes are high: Whenever you see or do something wrong, one campaign slogan earnestly declares, “You turn off the light in your heart.”

American observers may be forgiven for looking enviously at Cairo. We, too, have perceptions to correct aplenty. According to a recent Siena poll, for example, 22 percent of all Americans and a whopping half of all men aged eighteen to forty-nine regularly indulge in online betting. Two-thirds of the general population—and a heartbreaking three-quarters of all teens—regularly view pornography. We pop pills, post bilious missives online, and increasingly believe that violence is the inevitable path forward; 30 percent of respondents said just that in a recent survey conducted by NPR.

Is it time for us to follow the Egyptian example and ask Washington to embark on a campaign to snuff out vice? Most Americans are likely to find this proposition absurd. Overall trust in the government is the lowest it’s been in seven decades, which means that most of us barely expect civil servants to pick up our trash, let alone heal our minds and our hearts.

But while most of us agree that government intervention is unlikely to spur moral revival, the problems we face persist, and they exact an ever-growing toll. We now have decades of research suggesting that pornography (to focus on just one of our social ills) alters the brain, creates dependency, and leaves its habitual consumers far less likely to partake in healthy sexual relationships with other human beings, which may explain why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention informed us this year that our national birth rate has reached an all-time low.

An account of how and why we’ve let things get this bad could and should occupy battalions of scholars. But if you’re looking for a quick and easy fix by technocrats, don’t get your hopes up. We’ve become a nation of porn-addled, stoned gamblers because we attempted to solve a mighty spiritual crisis with the feeble tools of politics and policy.

How, for example, might we cure the young of their ruinous dependence on pornography? Whenever this question was asked in recent decades, our best and brightest—well-intentioned and sincere thinkers and lawmakers—have offered variations on the same theme: Ban it. Which, naturally, has rallied free-speech absolutists to rise and defend the smut flooding our screens as protected expression. Before you knew it, the debate sounded like it belonged more in the law school seminar room than in the public square. The same is true of the scourge of online gambling. The debate often starts—and frequently ends—with a 2018 Supreme Court case that allowed betting behemoths such as FanDuel to soar into a $31 billion valuation.

Don’t get me wrong. Legal niceties and policy-wonkery have their place. But missing from these conversations about legislation has been a simple and profound admission: We shouldn’t gamble on sports or watch strangers fornicate because, well, our Egyptian brothers have it right—because when you do so, you turn off the light in your heart. That light, once extinguished, is difficult to turn back on. And without it, we’re not recognizably human.

Why are we so reluctant to talk forthrightly about right and wrong? Maybe it’s because we now live, as the writer Aaron Renn reminds us, in the “negative world,” an America in which the Judeo-Christian values that once informed the culture are viewed as oppressive, regressive, and bad. This means that parents, teachers, and members of the clergy must defend themselves and their young not only against torrents of temptation, but also against a zeitgeist eager to strip them of all moral authority.

Some resisted; many, alas, shrugged their shoulders and slunk away. Which, maybe, helps explain how an unlikely figure like Jordan Peterson—a Canadian psychologist who speaks and writes with the academic’s measured tone—became a cultural sensation simply by advising young Americans to make their beds each morning. He speaks plainly about things once taught matter-of-factly by mothers and fathers.

And herein we have the answer to our predicament. How do we get young people to swear off self-destructive behaviors? Easy enough: We tell them to. Make your bed. Stop watching porn. Delete the FanDuel app. Spend less time on your phone and more time in church or synagogue. Do it because you’re a human being, created in God’s image, not some animal governed solely by its appetites.

This may sound like a laughably simplistic solution. But some things are not complicated, and everything we observe all around us confirms that a direct approach works. Consider the so-called groypers—fans of the online provocateur Nick Fuentes. They revel in his declarations of love for Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, not because they share these demented views, but because they’re struggling to understand the place they occupy in society. This should come as no surprise. Spend decades telling young, white men that not much more than a bedsheet separates them from the Klan and, eventually, they’ll feel abandoned, enraged, and ready to pledge their allegiance to the first charlatan who swings by with tough talk and promises of cultural ascendance.

Rather than bemoaning Fuentes’s influence, we should recognize that he reveals an auspicious opportunity. Because if a spiteful and sordid worldview like the one peddled by Fuentes quickly gains followers, imagine how many more would follow the properly amplified word of God.

What we have, in other words, is a problem of communication, which is really a problem of finding a stiffer spine. Society’s lost boys (and girls) don’t want a marketer eager to appear relatable, or a scholar citing facts, or a politician offering frothy platitudes. They want real talk, the kind you can only get from a serious grown-up who loves you very much, so much so that he’ll be firm and demanding when strong words are needed. And when they can’t find grown-ups who speak directly and without equivocation, they rush to the next best thing—to petty demagogues who urge them to burn down the house, never telling them that doing so will leave them homeless.

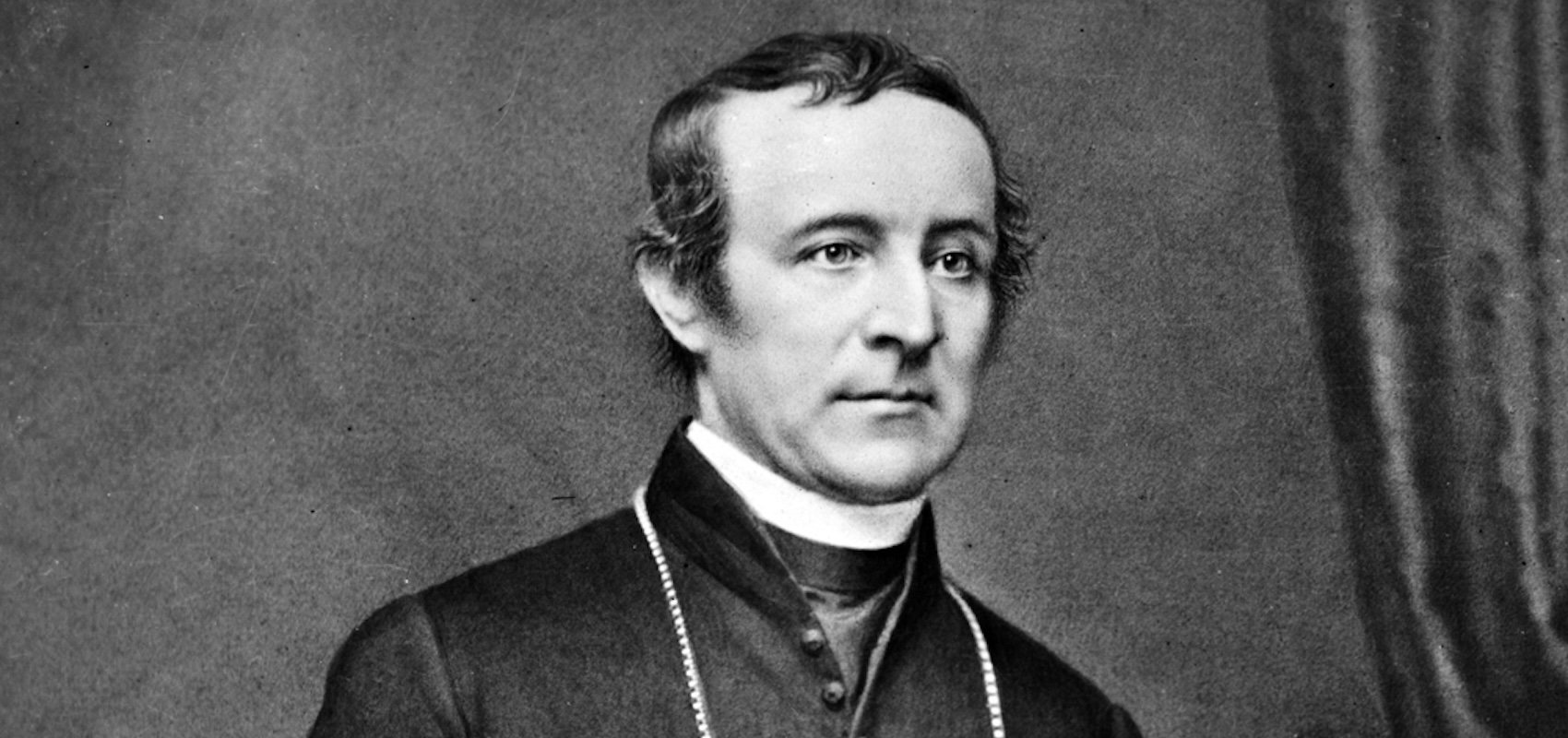

If you doubt that the “right is right” and “wrong is wrong” approach works, you might want to take a stroll down Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. There, between 50th and 51st Streets, you’ll see the world-famous St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the cornerstone of which was laid down by John Hughes, the archbishop of New York from 1842 until his death in 1864. Known as Dagger John, Hughes recognized that his parishioners, mostly impoverished immigrants newly arrived from famine-stricken Ireland, were in danger of losing all hope. Hughes fought for them—sometimes, legend has it, quite literally, by thrusting himself into scuffles. And as he battled, he preached the rigid gospel of personal responsibility and discipline. Within a generation, a population known primarily for producing prostitutes and petty thieves gave the city its schoolteachers, police officers, and community leaders. Dagger John, as one biographer observed, “re-spiritualized” his flock, not with soapy, feel-good slogans or “meeting people where they are,” but with clear instruction: Do the right thing and shun the wrong. He instilled in his flock a moral purpose that allowed them to see themselves as something greater than the sum of their indignities.

Let us, then, unleash a few dozen more Dagger Johns and Dagger Janes, as loving as they are strict, ready to sacrifice much for those whom they serve, but demanding growth and change in return. Let us parent today’s errant children (some of whom are well into adulthood). Give them clear and unequivocal moral instruction, and they won’t turn their insecurities into political performance pieces. Our politics and our technologies might’ve changed, but human nature never does. All we need is a firm hand, sometimes caressing us lovingly, sometimes giving us a much-needed shove in the right direction.

Just War Theory and Epic Fury

The machines of war have sprung into action once again in the Middle East. Bombs are falling…

What the USCCB Gets Wrong About Birthright Citizenship

In the wake of the 2007 Supreme Court decision to uphold Kansas’s ban on partial birth abortion,…

Politics of the Professoriate (ft. John Tomasi)

In the latest installment of the ongoing interview series with contributing editor Mark Bauerlein, John Tomasi joins…