Many find Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit daunting to read. I don’t pretend that it’s easy sledding. But the main thrust is not difficult to grasp. The work offers a genealogy: What explains the world in which we live? Where does truth come from?

Most answers throughout history have been theocentric. In one fashion or another, God (or the gods) gets things going. The power that forms reality comes down from above. Hegel was and remains seminal for modern thought, because he answered genealogical questions without reference to the transcendent. Our circumstances, conditions, identities—indeed, our truths—are emergent. The power that fashions all things comes from below.

Materialist philosophies were formulated in antiquity. Epicurus speculated that reality was composed of atoms circulating in a void—and nothing else. The power comes from below, and it stays there. Epicurus counseled calm acceptance of the brute meaninglessness of existence. There’s a coldness in the unfeeling atoms, and in this approach to life. But there’s also a hardness that is invulnerable and enduring—again like the atoms.

Hegel’s view is very different. Rather than inert matter, Hegel’s primal reality is time itself, which is dynamic and alive. Things happen! And they do so in accord with an inbuilt logic. The term Hegel uses for the logic of time and its unfolding is “dialectic.” Developments speak to other developments. The conversation of situations and events advances and evolves, leading to who we now are, living and thinking as we do.

Hegel’s innovation is not found in the supposition that time brings changes. That’s a banal truth. Rather, Hegel depicts history as a shaping power, singular and omnipotent in its effects. In this regard, it is fitting that we should capitalize “History,” for it is in a real sense our creator.

The final section of Phenomenology of Spirit concerns the end point of History: “Absolute Knowledge.” I remember the first time I read Hegel. His claim to have reached the final and consummating stage of knowledge struck me as absurdly boastful. He did not know of the existence of Pluto, nor had he knowledge of the principles of modern physics! As the years have gone by, however, I’ve come to see that Hegel was correct, not about the end of history, but about modernity’s self-conception, which has become very nearly universal. In 2026, most firmly believe that we are creatures of History, not to some degree (as many premodern thinkers allow) but finally and essentially.

In a series of lectures given in 1969 (Time as History), the Canadian thinker George Parkin Grant noted the depth of modernity’s commitment to seeing the human condition as essentially historical, even as the specific story that the German philosopher told about History’s inner genius no longer persuades us. Grant observes our common ways of speaking about History: It “demands, commands, requires, obliges, teaches, etc., etc.” The arc of History bends toward justice, we are reminded. Some are “on the side of History,” while others, working against its genius, will be “judged by History.”

In the late 1960s, when the Jesuit theologian Bernard Lonergan was at the peak of his influence, he gave a lecture that framed a version of Hegel’s claim to Absolute Knowledge: “The Transition from a Classicist World-View to Historical-Mindedness.” Lonergan distinguished between the classicist worldview, anchored in unchanging and timeless truth, and the historical outlook, which recognizes that human consciousness evolves in accord with historical change. As modern man comes to recognize the fundamental role of history, there’s no turning back, no possibility of returning to the classical worldview, short of a stultifying and intellectually irresponsible denial of what we now know about History’s shaping power.

Again, historical-mindedness is not simply historical knowledge. It is not found in the recognition that the ratification of our present Constitution more than two hundred years ago provided the United States with its political form. Rather, historical-mindedness rests on the fundamental conviction that the historical process determines our beliefs about what is true, good, and beautiful. The great modern achievement is to know that this is so—Absolute Knowledge. The knowledge is absolute, not in a particular way, but in general. We now know the creator of the transcendentals: History.

Absolute Knowledge is paradoxical. Our world is created by History, which suggests the passivity of clay on a potter’s wheel. Moreover, as the modern claim on behalf of History’s power undermines the old confidence in unchanging truths, an enervating relativism would seem to be our fate. If all truth is historical, then no truth is permanent. Moreover, as Grant observes, the knowledge that we make our own meaning threatens to blight its power to assure us.

It is true that modern historical consciousness has demoralized some with its relativism. But in the main, it has spurred great ambitions. As Hegel speculated, the modern stage of History’s career has imbued us with knowledge of her inner workings, empowering us to be her handmaidens. Lonergan’s formulation: “Modern man is fully aware that he has made his modern world.” Now “fully aware,” we must take responsibility for making a better future, seeking progress, fending off decline, and redeeming our flawed historical inheritance.

This column is not the place to survey the redemptive ideologies that have dominated the modern era. It is sufficient to note that they call for us to ally ourselves with History, which impresses upon us a duty: the task of overcoming present limitations and midwifing a new future. Instead, I want to focus on the way in which our spiritual lives have been transformed. Genealogies from above enchant reality. In the classicist worldview (to use Lonergan’s term), the most noble disposition is gratitude for what Grant calls “lovable actuality.” The highest form of intellectual life is contemplation, which seeks to glimpse the transcendent source of reality. The greatest virtue is love.

As we elevate historical consciousness to supreme status (Hegel’s Absolute Knowledge), we cast our vision toward the future, which lies before us. Our spiritual task is to marshal the power of History to make the world anew, rather than to recognize the world as good. Instead of pious gratitude, we prize righteous impatience. Activism—moral, political, economic, technological—replaces contemplation as the ideal. Karl Marx summed up this spiritual transformation in his Eleventh Thesis on Feuerbach: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” Mastery becomes the signal virtue of modernity.

It is a commonplace to say that we “can’t turn back the clock.” This formulation is meant to highlight the taken-for-granted fact that we’re modern men and women, formed by modern science and imbued with unprecedented technological power. And we possess not just science and technology, but also historical consciousness. Lonergan was quintessentially modern when he asserted that we are fully aware that we have made our world. And he was characteristically progressive as he assigned to “modern man” the responsibility for shepherding History toward higher ends.

Compare this deference to History with contemporary attitudes toward nature. We can’t turn back the clock, but we can make girls into boys. We’re foredoomed to be modern men and women, yet at the transhumanist cutting edge we can entertain the possibility of escaping the curse of death. Nature is be mastered, which means, as C. S. Lewis warned in The Abolition of Man, that our humanity must become raw material in the hands of the philanthropic “conditioners,” those imbued with grandiose dreams of making new realities, new truths.

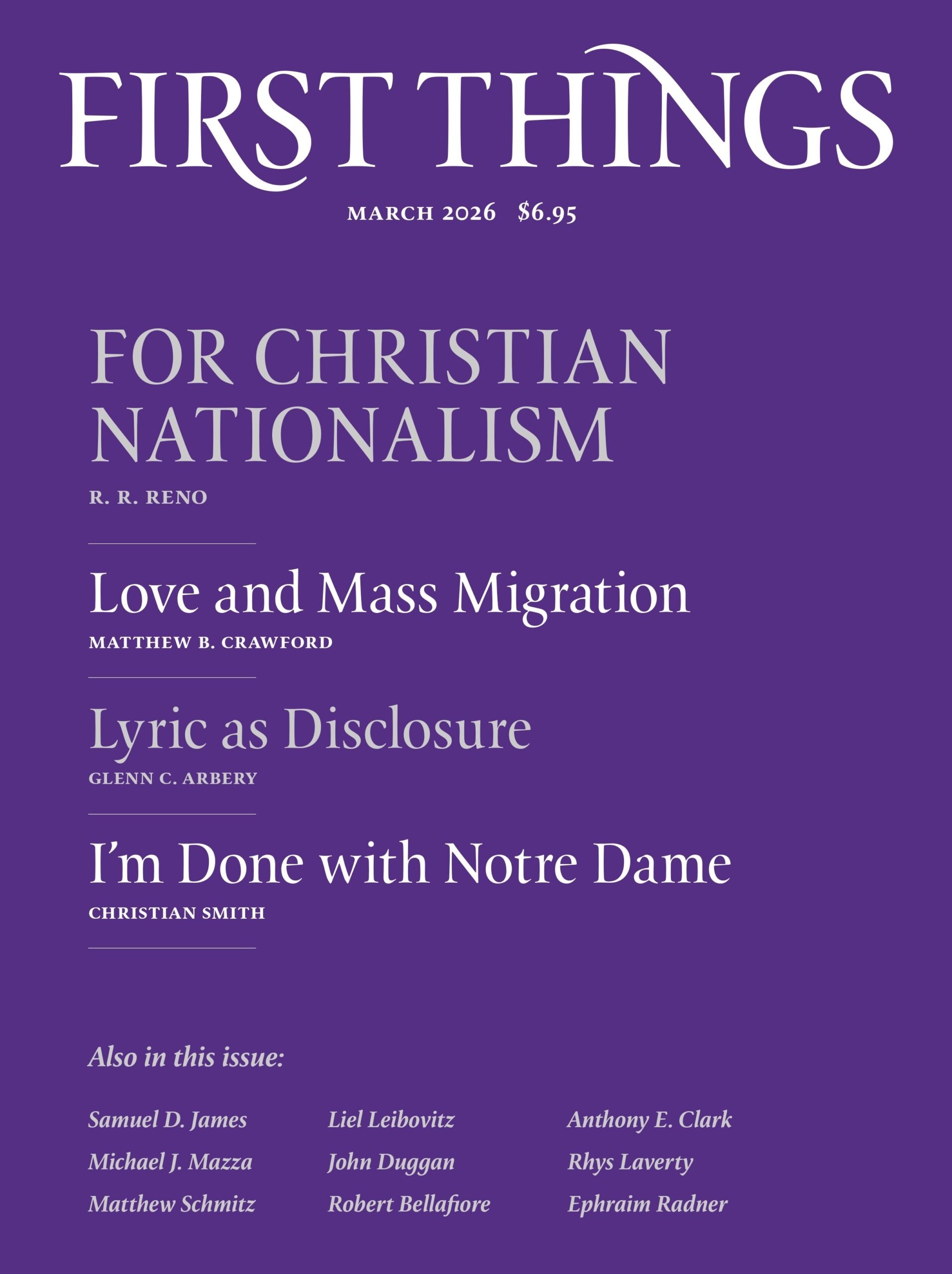

The dominion of Absolute Knowledge is daunting. Its power is evident in the prestige our educational institutions accord to “critique,” the enterprise of exposing and analyzing the factories of truth. George Grant laments, “Words that once summoned up receptivity have disappeared or disintegrated into triviality.” But we are not undone. In this issue, Glenn Arbery (“Lyric as Disclosure”) reminds us that poetic language discloses what can only be received, never mastered. Poetry is but one of many enchanting modes that operate outside the empire of Absolute Knowledge. Grant observes that remembering is often a golden moment of cherishing, which is especially palpable in the wrongly derided mood of nostalgia. And we still feel the passion of love, which desires union, not mastery.

Providence After the Death of God

Modern Christians confront a paradox that has shaped the last two centuries: The very idea that history…

Smooth Sailing

I regularly fume as I am caught in the chain of red lights that mark my rides…

Goodbye, SSPX

As expected, the head of the SSPX, Fr. Davide Pagliarani, has sent a letter to Cardinal Fernández…