It seems only a few years ago that I was calling myself “a man of the left.” Well, like the Jewish intellectuals who became “neoconservatives” in the 1960s and 1970s, I am a liberal who’s been “mugged by reality.” What has happened to the public discourse about race in this country in the course of the past decade has radicalized me. It is time to challenge the Zeitgeist.

I am a black American intellectual in an age of persistent racial inequality. I am an Ivy League college professor and a descendant of slaves. I came up in the 1950s and 1960s on Chicago’s South Side. I am a beneficiary of the civil rights revolution, which made possible for me a life that my forebears only dreamed of. I am an economist who believes in the virtue of markets, property, entrepreneurship, sound money, and free enterprise. I am a patriot who loves his country. I am a man of the West. I am an inheritor of its great traditions: Tolstoy is mine. Dickens is mine. Newton and Maxwell and Einstein are mine. So what, I ask, are my responsibilities? I feel compelled to represent the interests of “my people.” But that reference is not unambiguous! As an intellectual, I seek to know the truth and to speak such truths as I may be given to know. That is my purpose now, at a moment of “racial reckoning.” I declare that—no matter the political turmoil that may envelop us—my fundamental responsibility as a black American intellectual is to stay in touch with reality, and to insist that others do as well. I’m about speaking some unspeakable truths concerning race in America, about breaking free from “epistemic closure.” So, brace yourselves.

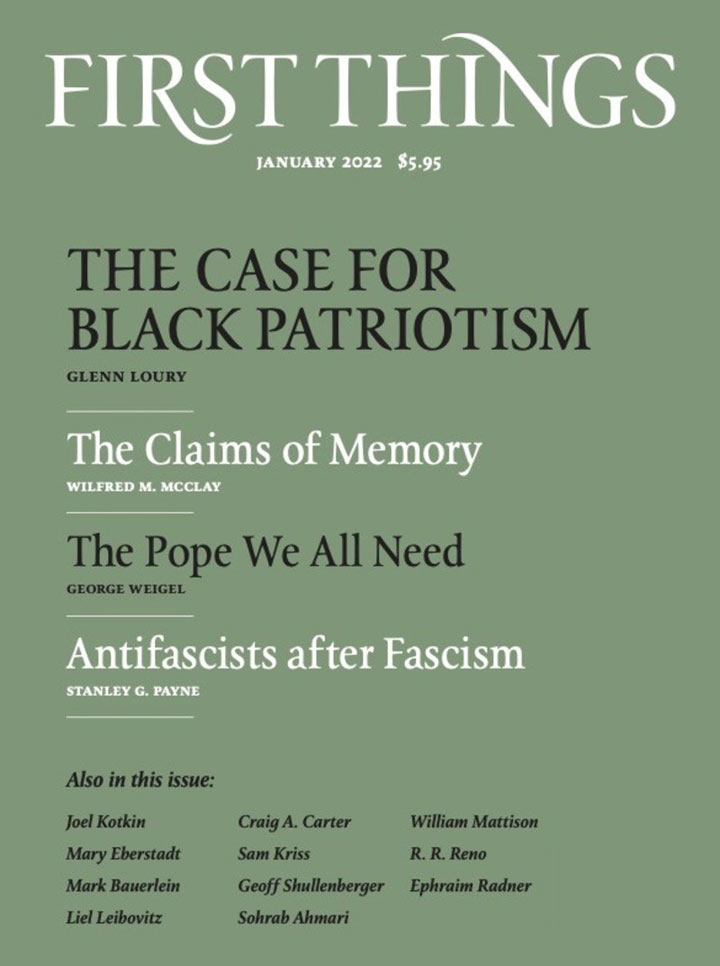

I wish to make the case for unabashed black patriotism—for the forthright embrace of American nationalism by black people. The currently fashionable standoffishness characteristic of much elite thinking concerning blacks’ relationship to the American project—exemplified by the New York Times’s 1619 Project—serves the interests, rightly understood, of neither the country nor of black Americans. The “America ain’t so great, and never was” posture, popular on campuses and in liberal newsrooms, is a sophomoric indulgence for blacks in the twenty-first century. Our birthright citizenship in this great republic is an inheritance of immense value. Our Americanness is much more important than our blackness.

We Americans, of all stripes, have a great deal in common, and our commonalities can be used to build bridges, undergirded by patriotism, between black America and the nation as a whole. We all finally want the same things. We want a shot at the American Dream. We want each generation to do better than the ones that came before it. We want to feel secure in our homes and in public. We want to live in clean and orderly communities with good services. We want the government to work for us, not the other way around. We want to be treated fairly by society and our institutions. We want personal freedoms so that, with reasonable restrictions, we can do as we please, including the right to fail. The list of our commonalities goes on. Connections among various groups in America could be stronger if we focused more on the things we have in common than on the things that divide us. Those who make their living by focusing on our differences believe that there is something fundamentally wrong with America. They’re wrong. We should resist their divisive rhetoric. It is easy to overstate the racial problems facing our country, and to understate what we’ve achieved.

Racial inequality is real. But American politics obsesses to an unhealthy extent about racial identity. Just how important is race? Is it an objective difference between people, like sex, or is it a social construct? Consider the increasing rate of interracial marriages and the growing number of people who view themselves as “multiracial.” What about culture and values? Aren’t they important, and don’t they transcend race? How do we explain the alienation that seems to afflict so many black Americans? These folks are being told by demagogues and pundits that we’ve gone back to the 1960s. They’re being led badly astray. Black votes are being sought through the gross exaggeration of legitimate concerns. We have reached a point where black multimillionaires like LeBron James seem to really think that they’re being hunted like rabid dogs by racist cops. Demonstrable facts seem insufficient to stop such false narratives. That is why it is so important for people like me to speak the truth.

As a relatively conservative black American, I have a concern about the conservative movement: By making generic, color-blind claims about America, conservatives allow themselves to remain silent on the issue of race. They say, “Everyone is (or should be) treated equally under the law,” and leave it at that. Of course, I agree with equality under the law. But what should we conservatives be saying about race in America? Is it enough that we agree on the adequacy of the constitutional framework to solve the problems that remain? Most conservatives would say yes. But for many, a defense of the constitutional framework is an excuse for going back to business as usual on the question of race. This is not good enough, substantively or rhetorically. Substantively, it allows conservatives to ignore the very real problems in black America, and very real problems of the least among us of every kind. Rhetorically, it plays into the hands of those on the left who have never met a problem that more government could not fix, and who point to conservatives’ silence on race as proof of their racism.

My conservative prescription for the problem of persistent racial inequality in the twenty-first century is as follows. First, fortify the mediating institutions—families, churches, civil associations—through which citizens, especially the most vulnerable, develop the competencies to enjoy the fruits of liberty that our constitutional framework can deliver. Second, the state can supplement, but it cannot substitute for, those mediating institutions. There are times when the state needs to step in; but solutions to problems in our communities can and should come from those communities. Third, each and every one of us who believes in modest national government and mediating institutions should look for the grassroots leaders in our own communities and quietly, without fanfare or virtue-signaling, ask how we can help them do the important work they do: educating children; helping wayward young men find their way; teaching the vocational skills that support gainful employment; instructing young mothers on how to meet their parental responsibilities; comforting those who have lost loved ones to gun violence; bringing “hope in the unseen” to those seeking spiritual enrichment. (If you detect a Tocquevillean sensibility in these prescriptions, that’s no accident.)

Here is an unspeakable truth: Socially mediated behavioral issues lie at the root of today’s racial-inequality problem. They are real and must be faced squarely if we wish to grasp why racial disparities persist. This is a painful necessity. Downplaying racial behavioral disparities is a bluff, a debater’s trick. Anti-racism activists on the left claim that “white supremacy,” “implicit bias,” and old-fashioned “anti-black racism” are sufficient to account for black disadvantage. Those who make such arguments are daring you to disagree with them. If you do not attribute pathological behavior to systemic injustice, you must be a “racist,” one who thinks that black people are intrinsically inferior. What are these folks saying when they declare that “mass incarceration” is “racism”—that the high number of blacks in American prisons is evidence of racial antipathy? To respond, “No. It’s mainly a sign of antisocial behavior by criminals who happen to be black,” is to risk “cancellation” as a moral reprobate. This is so even if the speaker is black. Just ask Justice Clarence Thomas.

Nobody wants to be cancelled. But we should all want to stay in touch with reality. Common sense and much evidence suggest that those in prison are mainly those who have hurt somebody, stolen something, or otherwise violated the basic behavioral norms that make civil society possible. Those who take lives on the streets of St. Louis, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Chicago are behaving despicably. Moreover, those who bear the cost of such pathology are almost exclusively other blacks. An ideology that ascribes this violent behavior to a racist conspiracy against black people is simply not credible. Why have so many been getting away with espousing it for so long?

Consider, also, the educational achievement gap. Anti-racism advocates want to shoot the messenger by abandoning standardized admissions tests, on the grounds that they are racially biased. These advocates are daring you to notice that some groups send their children to elite colleges and universities at much higher rates than other groups since their children’s academic preparation is vastly higher, better, and finer. Academic skills are acquired through effort; no one is born with them. So why are some youngsters acquiring them and others not? That is a very deep and interesting question. The simple answer, “Racism,” is laughable—as if such disparities had nothing to do with behavior, cultural patterns, what peer groups value, how people spend their time, or what they identify as being critical to their self-respect. Anyone who actually believes such nonsense is a fool.

Nor could any sensible person believe that the fact that 70 percent of African-American babies are born to unmarried women is either a good thing or an effect of anti-black racism. People say these things, but they don’t believe them. They are bluffing—daring you to observe the truth: that the twenty-first-century failures of African Americans to avail themselves of the opportunities created by the twentieth century’s civil rights revolution are palpable and damning. The end of Jim Crow segregation and the advent of equal rights were transformative for blacks. Yet now—a half-century down the line—we still observe significant disparities. I agree that this is a shameful blight on American society. But the plain fact is that some considerable responsibility for this sorry state of affairs lies with black people ourselves. Dare we Americans acknowledge this?

Another unspeakable truth: We need to put the police killings of black Americans into perspective. There are about a thousand fatal shootings of people by the police in the United States each year, according to a carefully documented database kept by the Washington Post. Roughly three hundred (about one-fourth) of those killed are African Americans, while blacks represent about 13 percent of the American population. Black people are overrepresented among these fatalities, though they still make up far less than a majority. (Twice as many whites as blacks are killed by police in this country every year. You wouldn’t know that from the activists’ rhetoric.)

Now, a thousand may be too many. I would be happy to discuss the training and recruitment of police, their rules of engagement, and the accountability they should face in the event they overstep their authority. These are all legitimate questions. And there is a racial disparity—though there is also a huge disparity in blacks’ rates of participation in violent criminal activity. I make no claims here about the existence of racial discrimination in the use of force by police, including non-lethal force. This is a debate on which evidence could be brought to bear.

But, regarding police killings, we are talking about three hundred black victims per year. Very few of these are unarmed innocents. Most are engaged in violent conflict with police officers. Some cases are like George Floyd’s, unquestionably problematic and deserving of scrutiny. Still, we need to bear in mind that this is a country of more than 300 million people, with scores of concentrated urban areas in which police regularly interact with citizens. Tens of thousands of arrests occur daily in the United States. These fatal incidents—which are extremely regrettable and sometimes reflect badly on the police—are nevertheless quite rare.

To put it in perspective: There were roughly 20,000 homicides in the United States last year; nearly half of them involved black perpetrators. The vast majority of these perpetrators took other blacks as victims. For every black person killed by the police, more than twenty-five others meet their ends because of homicides committed by other blacks. We must hold the police accountable for the way they exercise their power over citizens. But it is very easy to overstate the significance and extent of the abuses, as Black Lives Matter activists have done.

The claim that something called “white supremacy” or “systemic racism” has put a metaphorical “knee on the neck” of black America is a lie being told daily by prominent black spokesmen and repeated uncritically by the media. Let me speak plainly: The idea that I, as a black person, dare not leave my house for fear that the police will round me up, gun me down, or bludgeon me to death because of my race is ridiculous. The lifetime odds of a black man’s being killed by law enforcement are 1 in 1,000. The presentation of violent conflicts between police and African Americans as latter-day lynchings is preposterous. Fear of cancellation keeps many white people from saying so out loud—but it doesn’t keep them from thinking it. “White silence” is not “violence,” as the social justice warriors would have it. Neither is it tacit agreement. Nonetheless, it should worry us. People are not blind; they are not fools. Everyone can see what is happening on the mean streets of urban America. Rhetorical bullying and tantrum-throwing, much in evidence since the killing of George Floyd, won’t change the facts on the ground.

There is an even more fundamental point: The viewing of police killings through a racial lens poses a terrible threat to social cohesion in this country. Police killings are regrettable regardless of the race of the people involved. To emphasize race—an officer’s whiteness, a victim’s blackness—is to presume that the officer acted as he did because the young man was black. This assumption is seldom tested against the facts. Moreover, once we begin to racialize these events, we may not be able to limit the racialization to cases of white police officers killing black citizens. We may find that cases of black criminals killing unarmed white victims are viewed through a racial lens, as well. Since there are a great many such cases, this is a development no thoughtful person should welcome. Framing them as racial events is counterproductive in ways too obvious to detail.

When criminals harm people, they should be punished. They do not represent others of their race. White people should not view themselves in racial terms if a black person steals their automobile, beats them up, takes their wallet, breaks into their home, or abuses them. Anti-racism advocates are playing with fire by imparting a racial sensibility to police-citizen interaction. They may find soon enough that theirs is not the last word.

This brings me to yet another unspeakable truth: An ideology dominated by the terms “white guilt,” “white fragility,” and “white privilege” cannot exist except also to give birth to a “white-pride” backlash, even if the latter is seldom expressed overtly—its expression being politically incorrect.

If I were one of these “white oppressors”—constantly bludgeoned about the evils of colonialism, urged to tear down statues of “dead white men,” commanded to apologize for what my white forebears did to “peoples of color” in years past, ordered to settle my historical indebtedness by means of racial reparations—I might well ask myself: On what foundation does human civilization in the twenty-first century stand? I might enumerate the works of philosophy, mathematics, and science that ushered in the Enlightenment, that allowed modern medicine to exist, that gave us the beginnings of what we know about the origins of the species and the universe. I might tick off the great artistic achievements of European culture: the books, the paintings, the symphonies. And then, were I particularly agitated, I might ask these “people of color,” who think they can bully me into a state of guilt-ridden self-loathing: “Where is ‘your’ civilization?”

The paragraph above exemplifies “racist” and “white supremacist” rhetoric. I would never say it, or anything like it, myself. But I do notice that, if I were a white person, this reasoning might tempt me—and I suspect it does tempt a great many white people. We can wag our fingers at them, but they are a part of the racism-monger’s package. For how can we make “whiteness” into a site of unrelenting moral indictment without also making it the basis of pride, identity, and self-affirmation?

The New Nationalism encourages patriotism—a good thing—but it may sometimes be insufficiently attentive to the difference between healthy and unhealthy patriotism. Chauvinism and jingoism are unhealthy, especially when tainted by racial identity-mongering. The right idea here is the ethic of transracial humanism propounded by Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.: We, as citizens of this great republic, must strive to transcend racial particularism and stress the universality of our humanity and the commonality of our interests as Americans. The only way to address the legacy of historical racism without setting off a reactionary racial chauvinism is to march, even if fitfully and by degrees, toward a world in which no person’s worth is contingent upon racial inheritance—a world in which racial identity loses significance, as we learn how to “unlearn race,” as Thomas Chatterton Williams puts it. By contrast, those who promote anti-whiteness (as Black Lives Matter activists do) will reap what they sow, in a backlash of pro-whiteness. The folks who think they can insist on spelling “Black” with a capital “B” while keeping “white” in the lower case are likely in for a rude awakening.

The narrative we black Americans settle upon is crucial. Is this a good country, one affording opportunity to all who are fortunate enough to enjoy the privileges and bear the responsibilities of American citizenship? Or is it a venal, immoral, and rapacious bandit-society of plundering racists, founded in genocide and slavery, propelled by capitalist greed and anti-black antipathy? The evidence overwhelmingly favors the former. The founding of the United States of America was a world-historic event, by means of which Enlightenment ideals about the rights of individual persons and the legitimacy of state power were instantiated for the first time in real institutions. The United States of America fought fascism in the Pacific and Europe in the mid-twentieth century. Our democracy, flawed as it most surely is, has been a beacon to billions of people throughout the world. We faced down, under the threat of nuclear annihilation, the horror that was the USSR. On our shores, we have witnessed since the end of the Civil War the greatest transformation in the status of an enserfed people that is to be found anywhere in world history. Some 46 million strong, we black Americans have become by far the richest and most powerful large population of African descent on this planet. The question, then, is one of narrative. Will we blacks regard the United States as a racist, genocidal, white supremacist, illegitimate force? Or will we see our nation for what it has become over the last three centuries: the greatest force for human liberty on the planet?

The narrative we choose will influence our assessment of certain key periods in American history. There is, of course, the Civil War, which left more than 600,000 dead in a country of 30 million. The trauma of this event was felt for decades. The result of that war—and of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments enacted just afterward—was to make enslaved Africans and their descendants into citizens. In the fullness of time, we became equal citizens. Should equality have taken another hundred years? Should my ancestors have been enslaved in the first place? No and no. But we must not forget that slavery had been commonplace since antiquity. Emancipation, the freeing of slaves en masse as the result of a movement for abolition—that was a new idea. It was a Western idea, brought to fruition in our own United States of America. It would not have been possible without the philosophical insights and moral commitments cultivated in the Enlightenment—ideas about the essential dignity of human persons and about what legitimates a government’s exercise of power over its people. Slavery was a holocaust, out of which emerged something that advanced the morality and the dignity of humankind: emancipation. The abolition of slavery and the incorporation of African-descended people into the body politic of the United States of America were monumental, unprecedented achievements for human freedom.

Look at what has happened in the last seventy-five years. A huge black middle class has developed. There are black billionaires. The influence of black people on American culture is vast and has global resonance. Black Americans are rich and powerful, comparatively speaking. To put it in perspective, there are 200 million Nigerians, and the gross national product of Nigeria is just about $1 trillion per year. America’s GNP is more than $20 trillion a year, and we forty million African Americans claim roughly 10 percent of it. That is, we have access to ten times the income of a typical Nigerian. The very fact that the cultural barons and elites of America—who run the New York Times and the Washington Post, who give out Pulitzer Prizes and National Book Awards, who make grants for the MacArthur Foundation, who run the human-resource departments of corporate America—have bought into woke racialism gives the lie to the notion that the American Dream doesn’t apply to blacks. It most certainly and emphatically applies. To deny this is to tell our children a lie, a lie that robs black people of agency and self-determination. It is a patronizing lie that betrays a profound lack of faith in the capacities of black Americans to rise to the challenges, face the responsibilities, and bear the burdens of freedom.

Here is my final unspeakable truth: If we blacks want to walk with dignity—if we want to be truly equal—then we must realize that white people cannot give us equality. We need to seize equal status. I take no pleasure in it, but I feel obliged to report that equality of dignity, equality of standing, equality of honor, equality of security in one’s position in society, equality of commanding the respect of others—these cannot be handed over. We must wrest them from an indifferent world by means of hard work, inspired by the example of our enslaved and freed ancestors. We must make ourselves equal. No one can do it for us.

Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave and great abolitionist, in a famous speech of 1852 titled “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?,” asked America whether he had a share in the nation’s civic inheritance. Douglass was cautiously hopeful that America might be faithful to its founding principles and grant liberty and equality to his people. But he had to plead with his audience to consider the gravity of the circumstance; he had to indict his country for not standing up to its own ideals. That was in the 1850s. The question Douglass posed has since been answered by history: As a black American intellectual who loves his country, I can say without equivocation in the year 2021 that the Fourth of July is “Ours.” It belongs to me every bit as much as it belongs to you. The question confronting black Americans today is not whether we are included within the body politic of the United States; we emphatically and obviously are. Today’s question is not how to end our oppression. It is what we will do with our freedom, what we will make of the enormous inheritance that is our birthright citizenship in history’s greatest republic.

Glenn Loury is Merton P. Stoltz Professor of the Social Sciences at Brown University. This essay was adapted from a speech delivered at the 2021 National Conservatism Conference.