“Europeans didn’t only disinherit Aztecs and Incas. Continuously, since the sixteenth century, we have been disinheriting ourselves.”

—John Moriarty“There is no bloodless myth will hold.”

—Geoffrey Hill

We must have been fifteen or sixteen when we discovered the church visitor’s book. It was an old church, maybe medieval, and I would pass it with my school friends on our way to the town center. I’m not sure what possessed us to go in; it might have been my idea. I’ve always loved old churches. For a long time, I would tell myself that I liked the sense of history or the architecture, which was true as far as it went. Like the narrator in Philip Larkin’s poem “Church Going,” I would venture into any church I found, standing “in awkward reverence . . . wondering what to look for,” drawn by some sense that this was “a serious house on serious earth.” Obviously, there was no God, but still: The silence of a small church in England had a quality that couldn’t be found anywhere else.

This visit was less serious. A fifteen-year-old boy with his schoolmates can’t be admitting an interest in rood lofts. I’d like to say it was someone else’s idea to write in the visitor’s book, where other people had inscribed things like “what a beautiful building” and “I feel a tremendous sense of peace here,” but a man should never lie about matters of the soul. It was I who took up the biro and scrawled, “I WILL DESTROY YOU AND ALL OF YOUR WORKS! HA HA HA!” then signed it “SATAN.” A few days later, we came back and did it again. “DIE, NAZARENE! VICTORY IS MINE!” I think we’d been watching the Omen films. We kept going for weeks, wondering when we’d be caught. We never were, but one day we came in to find that all of our entries had been tippexed out and the pen removed. The fun was over. We went to the video shop instead.

More than thirty years later, in the early spring of 2020, I was reading the autobiography of the Irish philosopher John Moriarty and following the news about some new virus that was apparently spreading in China. Moriarty’s book is called Nostos—homecoming—and like all his work, it is impossible to summarize because it is less a narrative than a myth. One of its threads, though, is how Moriarty gave up on the simple, unconvincing Christianity of his Irish rural youth and left for Canada to become an academic, only to become equally disillusioned with the empty-can rationalism that characterizes postmodern intellectual culture. Something was missing. Was it Ireland? Moriarty threw in his academic career and moved back to the mountains of Connacht. He had lost faith in science, in the mind alone of itself, in an age that had disinherited its people. But even at home, some part of the jigsaw was missing.

Seeking it, whatever it was, Moriarty crashed into a devastating personal crisis. One day, walking in the mountains, he suddenly had a mystical vision that broke his world apart. “In an instant,” he wrote, “I was ruined.” He seemed to see into a great abyss in which all of his stories were dust: “I had been let through not to a heaven but to a void that was starless and fatherless.” For years, he wrote, he had been engaged in “a genuine search for the truth, not merely a speakable truth, but a truth I would surrender to.” Now he realized, with a terrible inevitability, that there was only one story that could hold what he had seen, only “one prayer that was big enough.” He had, he wrote, been “shattered into seeing.” Whether he liked it or not, he had become a Christian.

A truth I would surrender to. I put the book down. I didn’t know quite why, but Moriarty’s story had shaken me. I realized that I had been searching for years for a truth like that. “How strange!” he had written. “Christianity making sense to me!” Somehow, the way he was telling the story—interweaving the Gospels with the Book of Job, the Mahabharata, the Pali Canon of the Buddha, the folk tales of Ireland, the poems of Wallace Stevens—was making sense to me too. What was going on?

“The story of Christianity,” wrote Moriarty, “is the story of humanity’s rebellion against God.” I had never thought of that ancient, tired religion in this way before, never had reason to, but as I did now I could feel something happening—some inner shift, some coming together of previously scattered parts designed to fit, though I had never known it, into a quiet, unbreakable whole.

A truth I would surrender to. What was this abyss inside me, this space that had been empty for years, that I had tried to fill with everything from sex to fame to politics to kenshō, and why was something chiming in it now like a distant Angelus across the western sea?

For the thing which I greatly feared is come upon me,

And that which I was afraid of is come unto me.

Something was happening to me, and I didn’t like it at all.

Urban England in the eighties was not, shall we say, a spiritually rich environment. My family never set foot in a church when I was growing up, which suited me fine. The nearest I came to serious religion was probably through my best friend, who was from a Pakistani family. He’d been on the hajj to Mecca and fasted for Ramadan and did all the other things that Muslims did, which I knew very little about. This was before Islam became a political lightning rod and everyone felt they had to develop strong opinions about it. All I knew was that my friend thought religion was real, which seemed quaint and very un-English. We in the modern world had long grown out of superstition.

Still, at least my friend’s religion seemed to pulse with some sort of living energy. The same could not be said of the Christianity which, when I was a child, was still at least nominally the national faith. I grew up singing hymns, listening to parables recited by teachers at morning assembly, and performing in Christmas nativity plays with a tea towel tied around my head. I knew the Lord’s Prayer by heart. Whether I liked it or not, I was taught as a child the outline of the Christian story—the story that had shaped my nation for more than a thousand years. I didn’t realize that my nation was surviving on spiritual credit, and that it was coming close to running out.

Back then, there were two distinct flavors of Christianity, both of which I tried to avoid. One was the fusty old Church of England variety. You would see this if you had to go to a wedding or a funeral, or when a vicar was invited to give a sermon at school. The vicar would be a slightly Victorian figure, an older man almost dainty in his manners, trying his best to speak in a dying tongue to a generation of kids more interested in their ZX Spectrums. The Victorian vicar would hand out morality lessons from a man who had lived two thousand years ago and whose core imagery might as well have been from Mars: wine presses, fishing boats, vineyards, masters and servants, virgins. The basic pitch seemed best summed up by Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which I’d rather have been reading than listening to a vicar: “One man had been nailed to a tree for saying how great it would be to be nice to people for a change.”

The second flavor was the trendy vicar. Unlike his predecessor, the trendy vicar was plugged into the spirit of the age. He knew that instead of bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist, we were watching The Young Ones and playing Manic Miner, and he was on our side. The trendy vicar had a clipped beard and wore jeans and sang folk songs about how Jesus was our friend, and gave awkward, vernacular sermons in which biblical stories were interspersed with references to EastEnders or Dallas or Michael Jackson songs. Despite his good intentions, the trendy vicar was much worse than the stuffy vicar. At least the Victorian sermons were in some way otherworldly, as religion should be. If it was pop culture we wanted, and we did, we were better off sticking with the real thing, which was to say the thing without any Jesus in it.

So, I had no reason to take any notice of religion in general or Christianity in particular. My Muslim friend had a faith that was passed to him by his family and was clearly a central part of their worldview. Nothing similar was offered to me, and even if it were, it would have been undercut by the wider cultural narrative. The school may have had mandatory religious education classes, but the age taught another faith: Religion was irrelevant. It was authoritarian, it was superstitious, it was feeble proto-science. It was the theft of our precious free will by authorities who wanted to control us by telling us fairy tales. It repressed women, gay people, atheists, anyone who disobeyed its irrational edicts. It hated science, denied reason, burned witches and heretics by the million. Post-Enlightenment liberal societies had thrown off its shackles, and however hard both species of vicar tried to prevent it, religion was dying a much-needed death at the hands of progress and reason.

Et cetera.

Still, there was enough truth in this story to fuel the intellectual anger of the Dawkins-esque teenage atheist that I later became. People had walked away from the church by choice, after all, and not just because they all wanted to have premarital sex. The message seemed irrelevant. Across Europe, the exodus was happening. Corrupted, tired, suddenly powerless, Christianity was dying in the West. And why not? I hadn’t seen anything relevant in it. Where was the mystery? Where was the promised connection with God? Who was this God anyway? A man in the sky with a book of rules? It was long past time to move on.

I didn’t know back then that the Christian story is the story of our rebellion against God. I didn’t know that by taking part in that rebellion I had become part of the story, whether I liked it or not. I didn’t know, either, why Christians see pride as the greatest sin. I only knew that I could argue a good case for the injustice of the world made by this “God,” and the silliness of miracles, resurrections, and virgin births. I knew I was cleverer than all the people who believed this sort of rubbish, and I was happy to tell them so.

I kept visiting empty churches. I just didn’t tell anyone.

Up on the mountains of England and Wales, I had my own visions. Walking and camping on the hills for weeks with my dad, I felt something settle within me that was more real than any theology. I might have been a teenage atheist, but my atheism amounted mainly to arguing with Christians. The religions of the book were obviously nonsense, but I knew there was something going on that humans couldn’t grasp. Trudging across moors, camping by mountain lakes as the June sun set, I could feel some deep, old power rolling through it all, welding it together, flowing from the land into me and back again. With Wordsworth, I was dragged under by “A motion and a spirit, that impels / All thinking things, all objects of all thought / And rolls through all things.” Nothing humans could build could come close to the intense wonder and mystery of the natural world; I still believe that to be self-evidently true. This was my religion. Animism, pantheism, call it what you will: This was my pagan grace.

Years of environmental activism followed. Working for NGOs, writing for magazines, chaining myself to things, marching, occupying: Whatever you did, you had to do something, for the state of the Earth was dire. Nobody with eyes to see can deny what humanity has done to the living tissue of the planet, though plenty still try. There were big, systemic reasons for it, I discovered: capitalism, industrialism, maybe civilization itself. Whatever had got us here, it was clear where we were going: into a world in which industrial humanity has ravaged much of the wild earth, tamed the rest, and shaped all nature to its ends. The rebellion against God manifested itself in a rebellion against creation, against all nature, human and wild. We would remake Earth, down to the last nanoparticle, to suit our desires, which we now called “needs.” Our new world would be globalized, uniform, interconnected, digitized, hyper-real, monitored, always-on. We were building a machine to replace God.

Activism is a staging post on the road to realization. Dig in for long enough and you see that something like climate change or mass extinction is not a “problem” to be “solved” through politics or technology or science, but the manifestation of a deep spiritual malaise. Even an atheist could see that our attempts to play God would end in disaster. Wasn’t that a warning that echoed through the myths and stories of every culture on Earth?

Early Green thinkers, people like Leopold Kohr or E. F. Schumacher, who were themselves inspired by the likes of Gandhi and Tolstoy, had taught us that the ecological crisis was above all a crisis of limits, or lack of them. Modern economies thrive by encouraging ever-increasing consumption of harmful junk, and our hyper-liberal culture encourages us to satiate any and all of our appetites in our pursuit of happiness. If that pursuit turns out to make us unhappy instead—well, that’s probably just because some limits remain un-busted.

Following the rabbit hole down, I realized that a crisis of limits is a crisis of culture, and a crisis of culture is a crisis of spirit. Every living culture in history, from the smallest tribe to the largest civilization, has been built around a spiritual core: a central claim about the relationship between human culture, nonhuman nature, and divinity. Every culture that lasts, I suspect, understands that living within limits—limits set by natural law, by cultural tradition, by ecological boundaries—is a cultural necessity and a spiritual imperative. There seems to be only one culture in history that has held none of this to be true, and it happens to be the one we’re living in.

Now I started to dimly see something I ought to have seen years before: that the great spiritual pathways, the teachings of the saints and gurus and mystics, and the vessels built to hold them—vessels we call “religions”—might have been there for a reason. They might even have been telling us something urgent about human nature, and what happens when our reach exceeds our grasp. G. K. Chesterton once declared, contra Marx, that it was irreligion that was the opium of the people. “Wherever the people do not believe in something beyond the world,” he explained, “they will worship the world. But above all, they will worship the strongest thing in the world.” Here we were.

I went searching, then, for the truth. But where to find it? Elders, saints, and mystics are notable these days for their absence. In their place we are offered a pick’n’mix spirituality, on sale in every market stall and pastel-shaded hippy web portal. A dreamcatcher, a Celtic cross, a book about tantra, a weekend drum workshop, and a pack of tarot cards with cats on them, and hey, presto: You’re ready for your personalized “spiritual” journey. On the other side, you will find no exhortation to sacrifice or denial of self, and certainly no battered and bleeding god-man calling you to pick up your cross and follow him. No, you will find instead the perfect manifestation of everything you wanted in the first place: the magnification of your will, not its dissolution. Expressive individualism disguised as epiphany, the reaching prayer of a culture that doesn’t know how lost it is.

I wanted something more serious, something with structure, rules, a tradition. It didn’t even occur to me to go and ask the vicars. I knew that Christianity, with its instructions to man to “dominate and subdue” the Earth, was part of the problem. And so, I looked east. On my fortieth birthday I treated myself to a weeklong Zen retreat in the Welsh mountains. The effect of seven days of disciplined meditation in a farmhouse with no electricity was astonishing. Something in me flipped open. For the next five or six years, I practiced Zazen and studied the teachings of the Buddha. It is clear enough why Buddhism is taking off in the West as Christianity declines: Its metaphysical claims seem convincing, its practices, when taught properly, yield results, and as a tradition it is even older than Christianity. It is, in short, a serious spiritual path, but with none of the cultural baggage of the church.

And yet. As the years went on, Zen was not enough. It was full of compassion, but it lacked love. It lacked something else too, and it took me a long time to admit to myself what it was: I wanted to worship. My teenage atheist self would have been horrified. Something was happening to me, slowly, steadily, that I didn’t understand but could clearly sense. I felt like I was being filed gently into a new shape.

Something was calling me. But what?

Obviously, it wasn’t Christ. I had read the New Testament a few times, and I mostly liked what I saw. Who couldn’t admire this man or see that, at root, he was teaching the truth? Still, he obviously didn’t die and return to life, this being impossible, and without that, the faith built around him was nonsense. I was a pagan, anyway. I found God in nature, so I needed a nature religion.

This was how I ended up a priest of the witch gods.

The short version of the story is that I joined my local Wiccan coven. Wicca is a relatively new occult tradition, founded in the 1950s by the eccentric Englishman Gerald Gardner, who claimed he had discovered the ancient remnant of a pre-Christian goddess cult. He was fibbing, but the practice he sewed together out of older, disparate parts is strangely cohesive, complete with secret initiatory rituals, a law book that can be copied only by hand by initiates, magical teachings, spell work, protective circles, and, at the heart of it all, the worship of two deities: the great goddess and the horned god. All initiated Wiccans are priests or priestesses of these gods; there are no laity. My coven used to do its rituals in the woods under the full moon. It was fun, and it made things happen. I discovered that magic is real. It works. Who it works for is another question.

At last I was home, where I belonged: in the woods, worshipping a nature goddess under the stars. I even got to wear a cloak. Everything seemed to have fallen into place. Until I started having dreams.

I had known, I suppose, that the abyss was still there inside me—that what I was doing in the woods, though affecting, was at some level still playacting. Then, one night, I dreamed of Jesus. The dream was vivid, and when I woke up I wrote down what I had heard him say, and I drew what he had looked like. The crux of the matter was that he was to be the next step on my spiritual path. I didn’t believe that or want it to be true. But the image and the message reminded me of something strange that had happened a few months before. My wife and I were out to dinner, celebrating our wedding anniversary, when suddenly she said to me, “You’re going to become a Christian.” When I asked her what on earth she was talking about, she said she didn’t know; she had just had a feeling and needed to tell me. My wife has a preternatural sensitivity that she always denies, and it wasn’t the first time she had done something like this. It shook me. A Christian? Me? What could be weirder?

After the dream, it began to make sense. Suddenly, I started meeting Christians everywhere. They were coming out of the woodwork: strangers emailing me out of the blue, priests coming to me for help with their writing. I found myself having conversations with friends I’d never known were Christian, who suddenly seemed to want to talk about it. An African man contacted me on Facebook to tell me he had had a dream in which God had told him to convert me. “If you want to know God,” he told me, “you need to read the book He wrote. You know it already: It’s called nature.”

It kept happening, for months. Christ to the left of me, Christ to the right. It was unnerving. I turned away again and again, but every time I looked back, he was still there. I began to feel I was being . . . hunted? I wanted it to stop; at least, I thought I did. I had no interest in Christianity. I was a witch! A Zen witch, in fact, which I thought sounded pretty damned edgy. But I knew who was after me, and I knew it wasn’t over.

One evening, I was sitting in the kitchen of the house in which our coven had its temple. We were about to go in and conduct an important ritual. As we got up to leave, I felt violently ill. I was dizzy, I was sick, I was lightheaded. Everyone noticed and fussed over me as I sat down, my face pale. I had an overpowering feeling that I should not go into the temple. I felt I was being physically prevented from doing it. Someone had staged an intervention.

After that, there was no escape. Like C. S. Lewis, I could not ignore “the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet.” How much later was it that I was finally pinned down? I don’t remember. I was at a concert at my son’s music school. We were in a hotel function room, full of children ready to play their instruments and proud parents ready to film them doing it. I was just walking to my chair when I was overcome entirely. Suddenly, I could see how everyone in the room was connected to everyone else, and I could see what was going on inside them and inside myself. I was overcome with a huge and inexplicable love, a great wave of empathy, for everyone and everything. It kept coming and coming until I had to stagger out of the room and sit down in the corridor outside. Everything was unchanged, and everything was new, and I knew what had happened and who had done it, and I knew that it was too late. I had just become a Christian.

None of this is rationally explicable, and there is no point in arguing with me about it. There is no point in my arguing with myself about it: I gave up after a while. This is not to say that my faith is irrational. In fact, the more I learned, the more Christianity’s story about the world and human nature chimed better with my experience than did the increasingly shaky claims of secular materialism. In the end, though, I didn’t become a Christian because I could argue myself into it. I became a Christian because I knew, suddenly, that it was true. The Angelus that was chiming in the abyss is silent now, for the abyss is gone. Someone else inhabits me.

I am not a joiner, but I accepted, eventually, that I would need a church. I went looking, and I found one, as usual, in the last place I expected. This January, on the feast of Theophany, I was baptized in the freezing waters of the River Shannon, on a day of frost and sun, into the Romanian Orthodox Church. In Orthodoxy I had found the answers I had sought, in the one place I never thought to look. I found a Christianity that had retained its ancient heart—a faith with living saints and a central ritual of deep and inexplicable power. I found a faith that, unlike the one I had seen as a boy, was not a dusty moral template but a mystical path, an ancient and rooted thing, pointing to a world in which the divine is not absent but everywhere present, moving in the mountains and the waters. The story I had heard a thousand times turned out to be a story I had never heard at all.

Out in the world, the rebellion against God has become a rebellion against everything: roots, culture, community, families, biology itself. Machine progress—the triumph of the Nietzschean will—dissolves the glue that once held us. Fires are set around the supporting pillars of the culture by those charged with guarding it, urged on by an ascendant faction determined to erase the past, abuse their ancestors, and dynamite their cultural inheritance, the better to build their earthly paradise on terra nullius. Massing against them are the new Defenders of the West, some calling for a return to the atomized liberalism that got us here in the first place, others defending a remnant Christendom that seems to have precious little to do with Christ and forgets Christopher Lasch’s warning that “God, not culture, is the only appropriate object of unconditional reverence and wonder.” Two profane visions going head-to-head, when what we are surely crying out for is the only thing that can heal us: a return to the sacred center around which any real culture is built.

Up on the mountain like Moriarty, in the Maumturk ranges in the autumn rain, I had my own vision, terrible and joyful and impossible. I saw that if we were to follow the teachings we were given at such great cost—the radical humility, the blessings upon the meek, the love of neighbor and enemy, the woe unto those who are rich, the last who will be first—above all, if we were to stumble toward the Creator with love and awe, then creation itself would not now be groaning under our weight. I saw that the teachings of Christ were the most radical in history, and that no empire could be built by those who truly lived them. I saw that we had arrived here because we do not live them; because, as Auden had it:

We would rather be ruined than changed.

We would rather die in our dread

Than climb the cross of the moment

And let our illusions die.

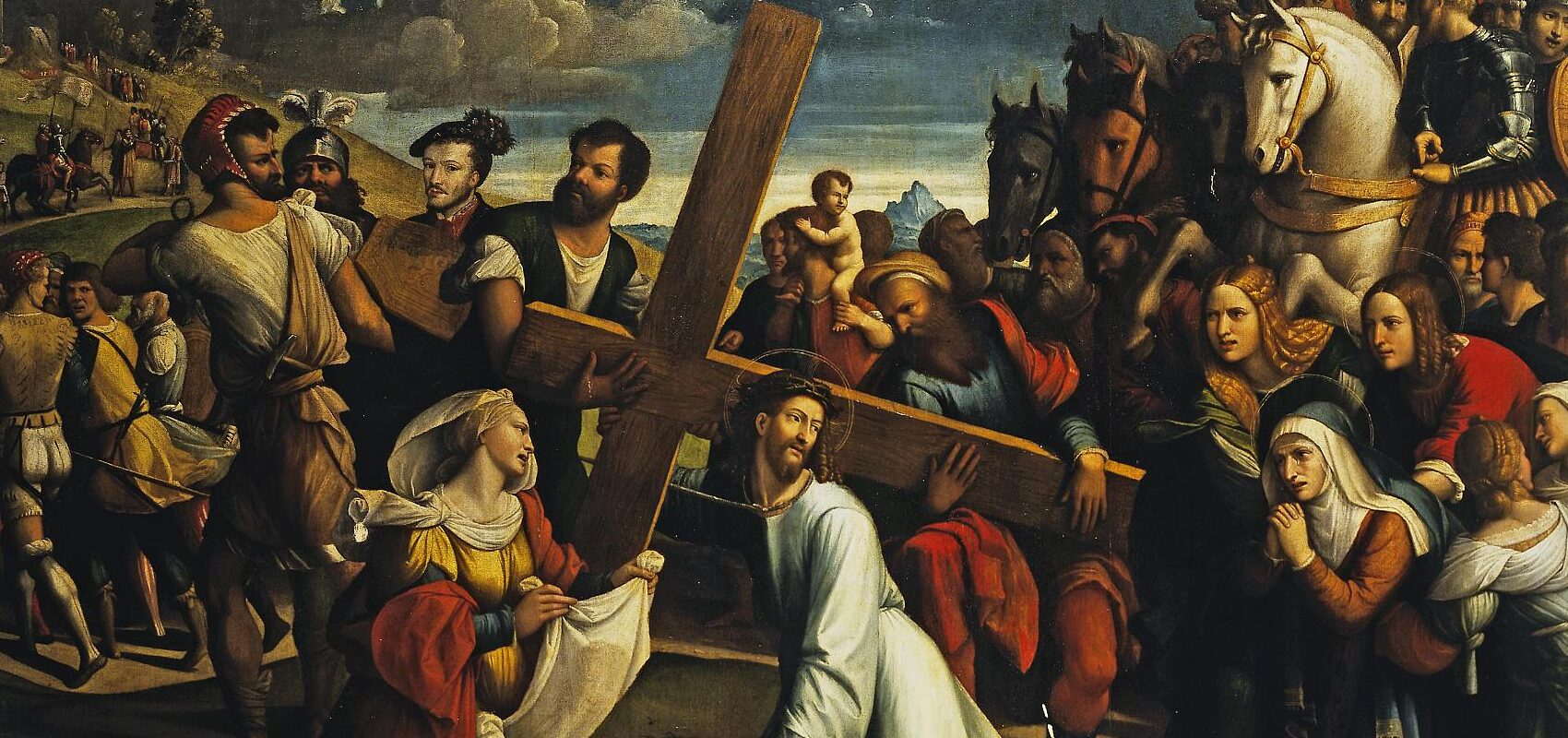

It turns out that both the stuffy vicars and the trendy vicars were onto something: The Cross holds the key to everything. The sacrifice is all the teaching. I am a new and green pupil. I can talk for hours, but ideas will become idols in the blink of an eye. I have to pick up my cross and start walking.

How can I feel I have arrived home in something that is in many ways so foreign to me? And yet beneath the surface it is not foreign at all, but a reversion to the sacred order of things. I sit in a monastery chapel before dawn. There is snow on the ground outside. The priest murmurs the liturgy by the light of the lampadas, the dark silhouettes of two nuns chant the antiphon. There is incense in the air. The icons glow in the half light. This could be a thousand years in the past or the future, for in here, there is no time. Home is beyond time, I think now. I can’t explain any of it, and it is best that I do not try.

I grew up believing what all modern people are taught: that freedom meant lack of constraint. Orthodoxy taught me that this freedom was no freedom at all, but enslavement to the passions: a neat description of the first thirty years of my life. True freedom, it turns out, is to give up your will and follow God’s. To deny yourself. To let it come. I am terrible at this, but at least now I understand the path.

In the Kingdom of Man, the seas are ribboned with plastic, the forests are burning, the cities bulge with billionaires and tented camps, and still we kneel before the idol of the great god Economy as it grows and grows like a cancer cell. And what if this ancient faith is not an obstacle after all, but a way through? As we see the consequences of eating the forbidden fruit, of choosing power over humility, separation over communion, the stakes become clearer each day. Surrender or rebellion; sacrifice or conquest; death of the self or triumph of the will; the Cross or the machine. We have always been offered the same choice. The gate is strait and the way is narrow and maybe we will always fail to walk it. But is there any other road that leads home?

Paul Kingsnorth is a novelist, essayist, and poet living in Ireland.