The majority opinion in Obergefell, written by Justice Kennedy, opens with a grand claim about the nature of freedom: “The Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity.” From this premise the decision follows. Add a truism of our age, which is that homosexual desires constitute an “identity,” and the syllogism is complete. The Constitution’s promise of liberty requires us to redefine marriage to allow men to marry men and women to marry women so that they can “express their identity.”

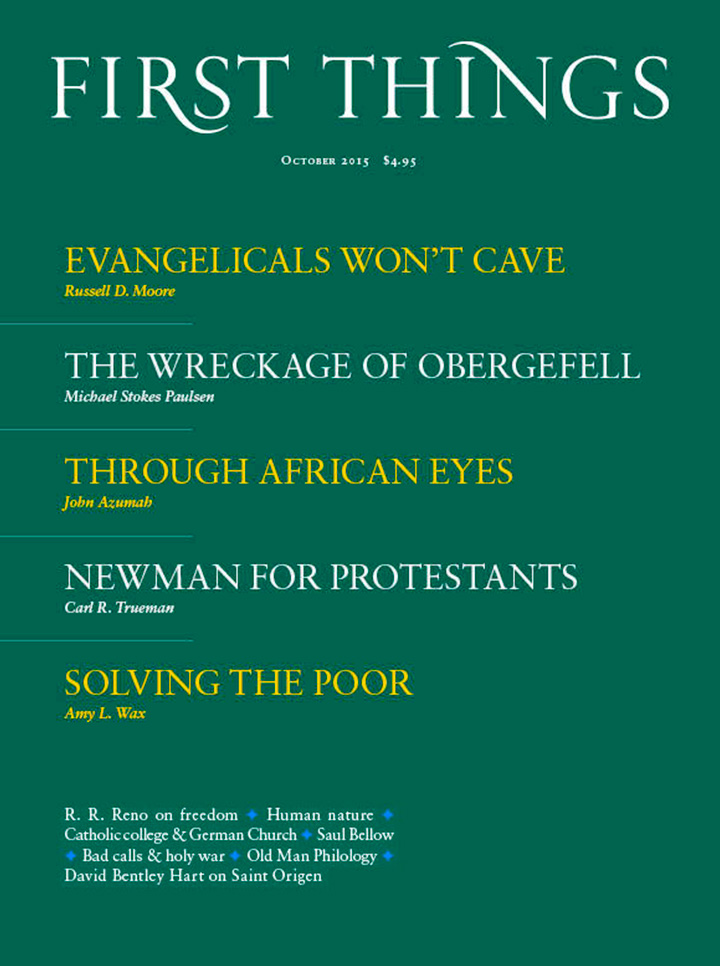

In this issue, Michael Stokes Paulsen analyzes Kennedy’s legal reasoning, such as it is. But I want to stick to his claim about liberty’s relation to identity. For this claim expresses a false and dishonest view.

On the one hand, Kennedy suggests that my identity is more than my will or free choice. It’s essential to me, and a just society provides the freedom to live in accord with my essential identity. Taken a certain way, that’s correct. I have an identity as a rational animal, and genuine freedom must include the liberty to make and consider arguments. Our constitutional rights of free speech and freedom of the press serve to promote that kind of freedom. I’m also a social animal, as well as a religious one. The constitutional rights of freedom of association and religion honor those aspects of my identity.

Yet in Kennedy’s formulation, identity is not something so fixed and stable as human nature. I can “define” my identity. In that sense, identity is not something freedom honors. It’s a covert word for freedom itself. This makes Kennedy’s formulation an empty tautology: The promise of liberty is the right to liberty. Freedom means living in accord with freedom.

This incoherence is an instance of the dishonesty widespread in cultural liberalism today. For example, we are told that homosexuality is an inborn trait, an essential part of a person’s makeup. At the same time, identity is plastic and open-ended, something to be discovered, even invented. LGBTQ today. Who knows what tomorrow? We’re told that individuals must be free to construct their own identities.

And so liberals have it both ways. If we call homosexual acts immoral, we’re failing to respect something essential about gay people. If we presume to define what is essential about anyone, including gay people, we’re encroaching on their freedom to define their identities. Identity is essential—and arbitrary. It’s the foundation for freedom—and a product of free choices. Heads, they win; tails, we lose.

Conceptual double-dealing is a characteristic of modern liberals. They defend as essential some quality or trait that we must have the freedom to live in accord with, all the while denying that there are essential truths that limit freedom. A similar self-contradiction is also common among moral relativists. They often work very hard to convince others of the truth of their relativism.

And so it goes. We’ve all experienced the almost invincible loyalties of modern liberals, especially in the cultural matters that now preoccupy them. Many know that the identity politics they acquiesce to, and even at times endorse, is illiberal. Yet they are unable to renounce them. Some recognize the brutality of abortion—but they cannot turn against our abortion regime. Most suspect that being male and female matters—but they are unable to stand against the sexual politics that say otherwise.

I’m often tempted to amplify my critiques of liberalism’s contradictions. For example, I’ve argued a number of times in these pages that promoting a view of identity as self-invention accords important advantages to the One Percent. It allows our technocratic ruling class to compliment themselves as morally progressive, with the added benefit of providing a therapeutic moral vocabulary with which to denounce populist challenges to their power. “Mrs. Johnson, I’m afraid those sorts of views can be very hurtful.”

But it doesn’t convince, at least not very often. To point out error and falsehood can be important. It often causes those with whom we disagree to hesitate. We can embarrass and fluster with well-formulated refutations. It’s even possible to induce second thoughts. But we rarely convince. That’s because the deepest mental poverty is one of imagination and courage, not reason and intelligence. In that sense today’s liberals—their self-contradictions and refusals to face the real sources and implications of their outlook—are all too human. When we can’t imagine alternatives, most of us remain loyal to the ideas that dominate our minds, even those we know to be false. We change our minds only when we can envision a more powerful truth.

There are many bad things about Obergefell. It puts an exclamation point on the sexual revolution and will very likely contribute to the further decline of marriage among those not wealthy and well educated. Transforming gay marriage into a fundamental constitutional right is sure to intensify the culture wars in America, for it provides proponents of gay rights with powerful legal tools to censure and destroy those who disagree with them. The Court’s decision represents an egregious judicial usurpation of the democratic process.

All this and more should be spelled out in detail. There is much to criticize. But I am sensible of something still more important. Obergefell is based on a false view of freedom—the liberty to define and express our “identity.” This false view has captured the imagination of our society. Even the best critiques of Obergefell won’t be effective unless we are able to help our fellow citizens imagine an alternative. We need to see freedom’s truth in order to free ourselves from its counterfeit.

A Vision of Freedom

In the Old Testament there are two straightforward words for freedom. One is chofesh, the word used in Exodus 21:2, where God’s law stipulates that a male Hebrew slave is to be freed after six years of service. The same word is used in the Israeli national anthem, evoking the hope that Jews will be a free people in their own land. The other is dror. Thus Leviticus 25:10, which stipulates that during the jubilee year freedom shall be proclaimed to all the inhabitants of the land. The same word appears in Isaiah 61:1, which prophesizes that the Anointed One will bind up the brokenhearted and proclaim liberty to the captives. But when it came to the Passover celebration, the ancient rabbis employed neither word. Instead, they turned to herut. Given its association with this central Jewish holiday, herut is the word most Jews associate with freedom.

This is more than a little strange. Herut shows up in 1 Kings 21:8, where it is translated as elders or ministers, those dedicated to God’s service. But that’s not the most important verse. Instead, it’s Exodus 32:16. There we find the account of Moses carrying down from Mount Sinai the two stone tablets, on which are engraved God’s Ten Commandments. Here things get really strange, for in this verse herut does not appear at all. Instead, we find harut, the word that means to carve or to engrave. Exploiting the fact that the Hebrew of the Torah is written with consonants only, the rabbinic tradition says that, in this instance, the word harut should be read as herut.

Verbal tricks of this sort are common in rabbinic teaching. Unlike Christianity, which articulates doctrines in explicit terms, often drawing on philosophical concepts, Judaism often spells out its doctrines by using provocative, sometimes counterintuitive interpretations of biblical verses or specific laws. In this case, a seeming misreading of Exodus 32:16 provides a definition of freedom. To be truly free, as the rabbis teach in their substitution of herut for harut, we must obey God’s commandments with a dedication and continuity of practice that engraves them onto our lives. This freedom is implied in the divine promise in Jeremiah 31:33: “I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts.”

The New Testament promotes the same account of freedom. Jeremiah 31:33 is repeated at Hebrews 8:10. It’s also evoked in 2 Corinthians 3:3, where St. Paul speaks of all those who are baptized as Christ’s missives delivered to the world. The letters are written not with ink but with the Spirit of God, not on tablets of stone but in our hearts. This, then, is the freedom for which Christ has set us free: to have the law of Christ engraved on our hearts. His way is the perfect law, which is the law of liberty (James 1:25), and the greater our loyalty to his way, the more we enter into true freedom. The more perfect our obedience, the more perfect our liberty.

This seems paradoxical to the modern mind. How can loyalty and obedience be the basis for freedom? Isn’t freedom being able to do what we want?

Yes, precisely. But it’s not so easy to do what we want, for there are great powers in the world that wish us to do as they want. For this reason, the ability to stand firm is the foundation of freedom. If we cannot be moved, we cannot be controlled. If we can resist domination, we are indomitable. The freest man is the one who can spit in the eye of those who imagine themselves all-powerful, asserting, “I will not.” We are most fully free when we can say, with St. Paul, “I am sure that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.” The martyrs testify to this freedom in a particularly powerful way.

There are natural analogies to the supernatural freedom of faith. Many men have overcome our natural bondage to fear of death out of loyalty, if not to something so abstract as their nation, then to their fellow soldiers. Countless mothers and fathers who seem quite ordinary are able to rise to heroic heights in defense of their children. Paternal and maternal love frees them from bondage to their selfish desires, allowing them to make personal and financial sacrifices for their kids. A binding love empowers. The rabbis were right about freedom. What’s engraved on our hearts strengthens our spines, allowing us to overcome personal weaknesses and stand up to external pressures.

The story of St. Maximilian Kolbe provides a powerful example of herut. He was a Franciscan friar and priest, active in publishing in Poland. Missionary work took him to Asia, but bad health brought him home. After the Nazi invasion of Poland he was arrested and sent to Auschwitz as a political prisoner. An incident in the camp led the commandant to single out ten prisoners to be executed as an example. One of the young men selected cried out, “My wife! My children!” Kolbe stepped forward, “Take me instead.” It was not a moment he had rehearsed. The future came to him unbidden, as the future always does, and he made it his own, and did so with a free act in a death camp designed to stamp out every possibility of freedom. Because he could stand firm in Christ, he could step forward.

Again, there are natural analogies to this supernatural freedom. A deep patriotic loyalty is active, not inert. It seeks to remedy a nation’s defects and develop its strengths. A true patriot applies himself to serve what he loves, which often requires ingenuity, creativity, and the ability to improvise when circumstances change. The same goes for a mother’s love for her child. To be stable in any love of a living person, living community, or living God—to have that love engraved in our hearts—always demands changes in our lives. John Henry Newman once said, “To live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.” He made this observation in a study of the development of doctrine, a story of change based in the Church’s unflagging loyalty to God’s revelation in Christ. Those freest to face the future are those most deeply bound to others in love.

Restoring a Culture of Freedom

Many Americans today lack places to stand. There are fewer and fewer enduring loves and demanding loyalties. The marketplace encourages us to consider our self-interest. Fewer and fewer people live where they were born. Families are less stable. All this and more takes place against a background of perpetual critique. Freud shows us that our families are not refuges in a cruel world. They are factories of psychological distress. Marx, Nietzsche, and Foucault unmask religion as an opiate and patriotism as a fool’s game. Reason is power’s favorite mask, and loyalty to truth makes one an unwitting pawn of oppressing forces that are always operating beneath the surface.

So we are less free, even as freedom is on everyone’s lips. Our growing underclass is enslaved to appetites, living in non-communities with failed schools and few functional social organizations. Middle-class life has become perilous. The press for free pre-kindergarten education is an indication that ordinary people are so hemmed in by powers that control their lives that they don’t feel able to raise their children. Even the rich are tightly yoked. They anxiously train their children for the mad meritocratic climb up the greasy pole of success. And we’re surprised the Nanny State grows? It cannot help but grow. The anxious and helpless can’t face the future, confident in their freedom. They want support and reassurance—in a word, today’s therapeutic liberalism.

We do not need greater constitutional protection of freedom in America, not even religious freedom. Or more precisely, legal freedoms are empty if we’re not able to claim them, which is exactly what happens when we have a diminished capacity for freedom. What’s needed today are renewed loves and loyalties.

Marriage presents an obvious instance. Although the institution has been gravely weakened by cohabitation, divorce, and now same-sex marriage, it remains for most people a powerful experience of herut. Wedding vows reflect our desire to engrave an enduring fidelity onto our lives.

The freedom is real, not imagined. Families often offer stubborn resistance, not just to the intrusions of the administrative state but also to the imperial penetration of mass culture into every aspect of our lives. The dining room table is under the mother and father’s authority, not the government’s, not Hollywood’s, not the New York Times’s.

Homeschooling represents a dramatic expression of parental freedom, as do private schools founded in order to stand against the spirit of the age. Here in New York, parents withdrew their children from mandatory standardized testing. It was a remarkable instance of grassroots protest, a stick in the eye of educational professionals who lay claim to their children. There’s nothing new here. As Plato recognized long ago, family loyalties work against collective control of life, which is why he prohibited parents from raising their own children in his ideal republic.

It’s no accident that the decline of marriage over the past few decades corresponds with a growth of government. Part of the explanation rests in the fact that families provide a safety net that’s very efficient because very well informed about what’s needed—and because it has a direct interest in making sure resources aren’t wasted. Two-parent families are also resistant to poverty. But there’s more to marriage and family than meeting material needs, far more. Marriage gives us a place to stand.

If we want to restore a culture of freedom, we need to rebuild the culture of marriage. Same-sex marriage makes that more difficult. It’s hard to engrave marriage vows into one’s life when society tells us that the institution can be redefined and reshaped as five judges see fit. But nobody promised us that what we need to do will be easy, certainly not the God of the Old and New Testaments.

Marriage and family are the places of our most common and often most powerful natural loves and loyalties. Stronger still are the bonds of faith, making religious renewal central to freedom’s renewal. This does not necessarily mean evangelizing the unchurched, though that’s a very good thing. More important, perhaps, will be the deepening of our own faith, turning what we affirm on our lips into words engraved on our hearts.

Unlike governments, the Church and the synagogue have no armies, no police forces, and no jailhouses. For the most part religious institutions lack the sophistication and reach of Big Media. They don’t have the analytic power of Big Data. They don’t pay big salaries or offer rich dividends. What they have is more powerful—a place to stand, and not an ordinary place, but one afire with the urgency of obedience to God’s will. At times in history these flames have turned religious communities into fierce proponents of divine causes, fomenting insurrections and pulling down governments, as is happening in the Middle East today.

But this is the exception. As a rule, the power of religious communities comes from their herut. This freedom is not based in legal protections. It does not flow from constitutions or declarations of human rights. Instead, it comes from invincible obedience to God’s will, an obedience that makes it impossible for secular powers to control the Church and the synagogue.

We already see this freedom at work in the debates about marriage. There’s nothing uniquely biblical about the view that marriage is between a man and a woman. It’s a widespread conviction in many cultures. Nor need religion have much to do with resisting the ideology of transgenderism. Common sense alone testifies against it. All true, but for the most part only religious people today seem able to speak up, dissenting in public from progressive ideologies about sex, family, and gender. Religious people resist the powerful voices in the media, entertainment, politics, and education. It seems we alone are free, free enough to overcome the efforts of intimidation and the relentless indoctrination.

Many are engaged in important efforts to protect our constitutional liberties. They’re right to defend freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and, today especially, freedom of religion. But in this time and in this place, herut matters more, much more. Our capacity, as religious believers, to resist legal coercion and social pressure will preserve liberty for everyone, and it will do so in ways much more powerful than well-crafted legislation and favorable judicial decisions. For as we stand strong, others can live on our leeward side, as it were, protected in their vulnerability by our boldness of speech and refusal to be coerced. The one child who stands up to the bully secures freedom for the whole schoolyard.

Herut does not just protect; it inspires. We should not underestimate how acutely our fellow citizens feel their bondage. One of my friends who has spoken out against gay marriage is a young professor at a large state university. It’s not a high-flying research university. Most of his students are first-generation college students. Some are illegal immigrants. Justice Kennedy’s definition of liberty as the freedom to define and express one’s own identity mocks them. They feel little sense of control over their lives, not knowing whether they will meet tuition bills or pay rent. To attain a middle-class life with a decent salary and a stable marriage—that’s an “identity” they’d welcome.

My friend’s public stances have brought him a great deal of grief. He’s been attacked again and again on social media. Activist groups work to get him fired. Moreover, nearly all his students are in favor of gay marriage. Yet his courses are full and popular. They respect him, even admire him. They see in him real convictions that allow him to resist domination and to take possession of his life. It’s a strength that makes him free, free in a way that they, too, wish to be free.

Our Future

It’s easy to be demoralized after Obergefell. Many powerful forces want to make us dhimmis, the Muslim word for non-Muslims who are allowed to exist as long as they don’t evangelize or challenge the supremacy of Islam. There are political dimensions to this pressure. The contraceptive mandate uses executive power to compel participation in one of the central practices of the sexual revolution. An educational accrediting agency tried to intimidate Gordon College because of its policies based on biblical principles for sexual morality. Recently, in a necessary first step toward bringing us in line with today’s sexual orthodoxies, a coalition of progressive organizations petitioned the Obama administration to reverse a policy of exempting religious organizations from nondiscrimination rules that otherwise apply to organizations that receive government grants.

We can defend our freedoms, using the appropriate political and legal means available. I’m guardedly optimistic. Recent Supreme Court decisions have been very solicitous of religious liberty. But there is a danger greater than oppressive and unjust laws, mandates, and regulations. Scholars of the Islamic world coined the term dhimmitude to describe the ways non-Muslims internalized their subordinate status, accepting it as normal and natural. As I’ve written elsewhere, we too are in danger of dhimmitude, an internalized submission to the progressives’ claim that they control the future.

We need to resist this tendency, for it’s a mentality based on the illusion that worldly powers are history’s master and thus set the ultimate conditions for our freedom. The seductions of this illusion are powerful, but historical reality testifies otherwise.

My wife is Jewish. Her ancestors lived for generations in the contested borderlands of Poland and Russia. Always vulnerable, they never enjoyed political freedom. Often persecuted, sometimes killed, they endured. That seems like a small thing, but is it not. Today the Polish and Russian aristocratic cultures that once lorded over them are gone. And what of the Soviet Union, the worker’s paradise that claimed to transcend all religion? What of the Thousand-Year Reich that imagined it would wipe Judaism from the face of the earth? They have gone down into the dust, just as the Roman Empire that razed the city of Jerusalem is no more, just as the medieval monarchies that drove Jews eastward into Poland and Russia centuries ago are no more.

Unlike these great, influential, and powerful civilizations, institutions, and ideologies, Judaism endures. The Torah is still read in the synagogue. It turns out that over those long and difficult centuries, only Jews had a future.They still have a future.

The same holds for Christianity. Along with the synagogue, the Church is the only surviving institution from antiquity. St. Paul is a living voice for us, as is St. Athanasius, St. Augustine, and countless others. In fact, the Church and the synagogue are the only surviving medieval institutions, or for that matter the only ones left from the early modern era.

The administrative state, democratic political institutions, and the limited-liability corporation are modern inventions. Today they absorb all social reality into themselves. Marriage is now a creature of the court, not a pre-political institution. The university has been subsumed into the techno-bureaucratic logic of our era. The one exception? Religious institutions. They endure on their own terms. They do not depend on secular authorities for authorization, licensing, or accreditation, as Christians in China remind us. They are free.

Yes, wealth seduces. Governments regulate, coerce, and punish. It has always been so. But neither wealth nor political power has created anything that has lasted. By contrast, over the long haul, religious faith has proven itself the most powerful and enduring force in human history. Let’s by all means be realistic about the great challenges we face after Obergefell. But let’s be sure a clear grasp of reality informs our realism. There will be no United States of America in one thousand years. But there will be synagogues and churches. The future is ours.

R. R. Reno is editor of First Things.

The Bible Throughout the Ages

The latest installment of an ongoing interview series with contributing editor Mark Bauerlein. Bruce Gordon joins in…

Redemption Before Christ

The latest installment of an ongoing interview series with contributing editor Mark Bauerlein. Gerald R. McDermott joins…

The Theology of Music

Élisabeth-Paule Labat (1897–1975) was an accomplished pianist and composer when she entered the abbey of Saint-Michel de…