In Four Quartets, T. S. Eliot notes, “The end is where we start from.” Our sense of when and how things reach their final consummation influences our views of past and present. We live in the reflected light of hopes and fears, which have as their object a not yet real but anticipated future. Christian theology has a word for reflection on this future and its backward casting shadow: eschatology. The word comes from the Greek eschaton, which means “last,” and thus eschatology involves formulating a theory of last things, end times.

At the recent National Conservatism Conference in Washington, D.C., Senator Josh Hawley gave a speech. He reflected on the eschatology implied by transhumanist optimism about technology. It presumes limitless progress, an ascent of time-limited, embodied human existence toward something limitless, something that transcends our bodies. Transgenderism participates in this eschatology as well. Our material bodies can be transcended as we search for our “true” identities.

Although Hawley did not mention him, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin gave powerful theological expression to the modern conviction that progress entails limitless ascent. He was a French Jesuit, trained in paleontology. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Teilhard was part of the scientific team that discovered Peking Man, the fossil remains of a forebear of Homo sapiens.

As a man of deep faith, Teilhard was concerned to understand human evolution as part of a larger divine plan. His solution was to imbue creation with an implacable desire for consummation. The title of his masterpiece, The Divine Milieu, conveys the thesis. God is “the ultimate point upon which all realities converge,” and therefore all things possess a capacity for spiritualization. The Christian vocation, Teilhard teaches, is to shepherd creation toward convergence with the divine. Here is how he puts it: “The pagan loves the earth in order to enjoy it and confine himself within it; the Christian in order to make it purer and draw from it strength to escape from it.” Our task, the deepest meaning of the Great Commission, is to assist in the spiritual evolution of the universe toward pure spirit.

There is a profound Christological dimension to Teilhard’s vison of final consummation. But that very same vision transcends the embodied particularity of Jesus on the cross, who seems to vanish into the Omega point (one of Teilhard’s terms for our final end). But I do not wish to tangle over the interpretation of Teilhard’s theology. Instead, I want to highlight Teilhard’s role as the spiritual custodian of a very modern belief in progress.

He was prohibited from publishing his theological writings in his lifetime. (He died in 1955). But after the Second Vatican Council, they were published, and Teilhard’s influence became immense. This is not surprising. The exploration of space, the progress in defense of human rights around the world, the rise of computing, the discovery of DNA, the great hopes for the United Nations, and more: The 1960s seemed to put the dark era of tyranny and ignorance in the rearview mirror. The future seemed bright—if we would but put our shoulders to the wheel of progress. And doing so involved more than material progress. We would make moral progress and spiritual progress as well. In this way, the spirit of that time was Teilhardian. It preached an eschatology of unending upward movement.

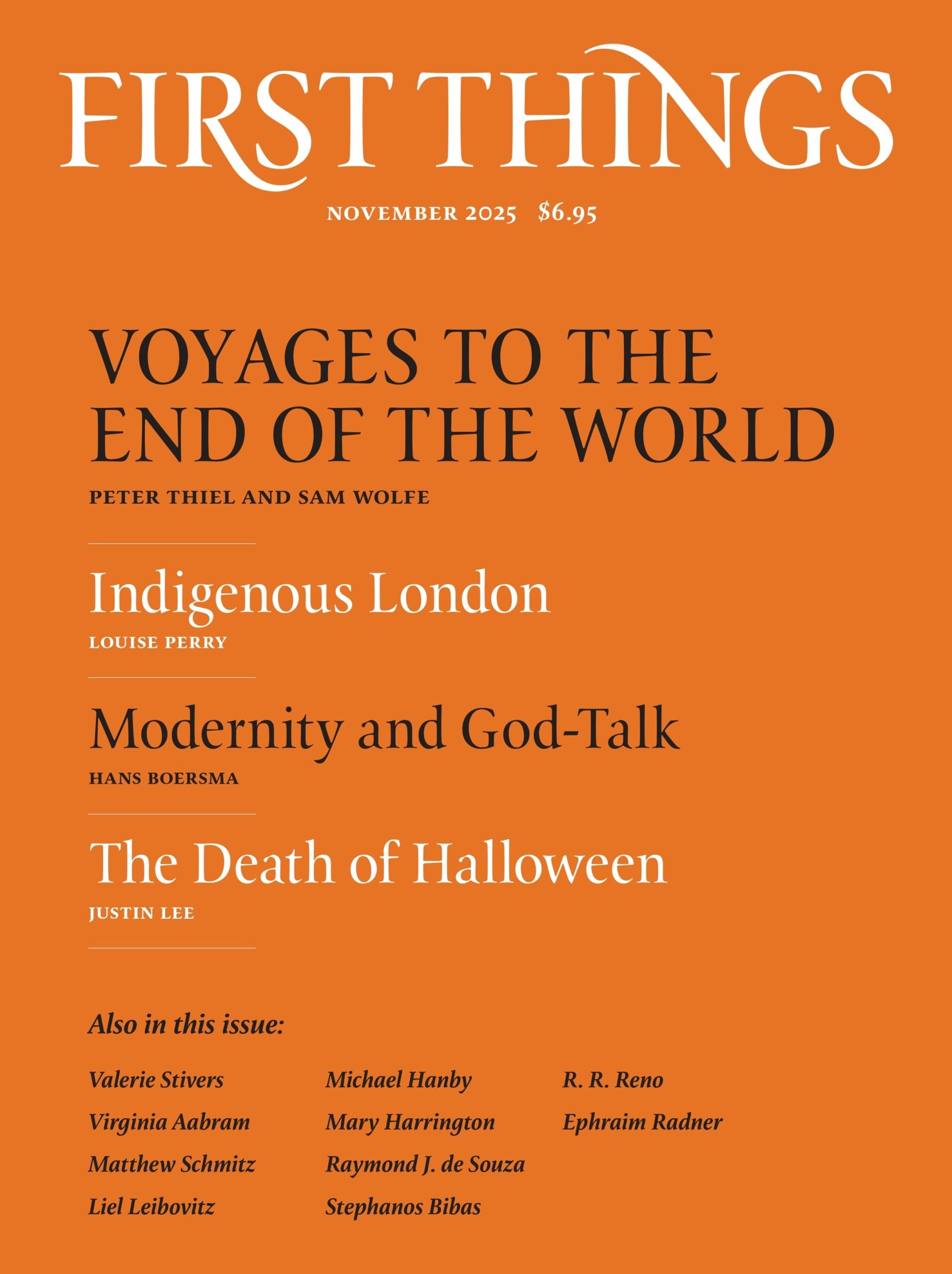

As Hawley was speaking at the conference and I was remembering my long-ago readings of Teilhard de Chardin, a thought struck me. In this issue of First Things, we are publishing “Voyages to the End of the World” by Peter Thiel and Sam Wolfe. The essay portrays an agonistic view of end times rather than the smooth, beneficent ascent characteristic of modern eschatology. In their readings of four literary works, Thiel and Wolfe depict technological progress as real—who can dispute that we possess new and unprecedented powers? Yet they evoke the unhappy possibility that this progress tends toward dehumanization rather than the bright, spiritualizing future Teilhard thought was woven into the golden fabric of reality.

An agōn is a contest, a conflict, a struggle. The Book of Revelation is clearly agonistic. The world’s future is sealed in Christ’s triumph over Satan. This eschatology implicates us in the final struggle. We are confronted with the agony of choice, the necessity to decide whom we shall serve and obey. Eliot captures this pressing necessity:

The dove descending breaks the air

With flame of incandescent terror

Of which the tongues declare

The once discharge from sin and error.

The only hope, or else despair

Lies in the choice of pyre of pyre–

To be redeemed from fire by fire.

Thiel and Wolfe are asking an important question: What is the role of the Antichrist in an age that believes in an ever-ascending, always trustworthy progress? He comes not as a vile beast, but as a savior, a peacemaker and healer. The Antichrist is “on the right side of history.” He often dons the disguise of “inevitable trends.” He leads research teams that promise us that we need not cultivate virtue to rule well. Technocratic expertise will provide scientific management—best practices! We need not prepare our souls for death; we can trust in science to deliver us. Here, then, is the temptation of the Great Seducer: We need not choose whom to serve and obey.

Image by Sailko, license via Creative Commons. Image cropped.

The Testament of Ann Lee Shakes with Conviction

The Shaker name looms large in America’s material history. The Metropolitan Museum of Art hosts an entire…

Dilbert’s Wager

Niall Ferguson recently discussed his conversion to Christianity. He expressed hope for a Christian revival, which he…

The Real Significance of Moltbook

Elon Musk thinks we may be watching the beginning of the singularity. OpenAI and Tesla AI designer…