Over the past two years, Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas passed laws requiring posters of the Ten Commandments to be displayed in public school classrooms. Predictably, critics argue that even these passive displays are unconstitutional.

Relying on Stone v. Graham (1980), a Supreme Court decision that is almost certainly no longer good law, three district courts and a panel for the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit have held that these statutes are unconstitutional. Among the claims made by the plaintiffs and cited in court opinions is that the version of the Ten Commandments utilized in these states is Protestant.

The three authors of this essay are, respectively, Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish. We understand that it is possible to present the Ten Commandments in ways that are distinctively Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish, but the text utilized by Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas is, in fact, nonsectarian. To understand why, it is necessary to first consider how this text came to be.

Shortly after the Second World War, a Minnesota judge named E. J. Ruegemer became concerned with what he perceived to be the rise of juvenile delinquency. He believed that “if troubled youths were exposed to one of mankind’s earliest and long-lasting codes of conduct, those youths might be less inclined to break the law.” He formed a committee “consisting of fellow judges, lawyers, various city officials, and clergy of several faiths” to develop a “version of the Ten Commandments which was not identifiable to any particular religious group.”

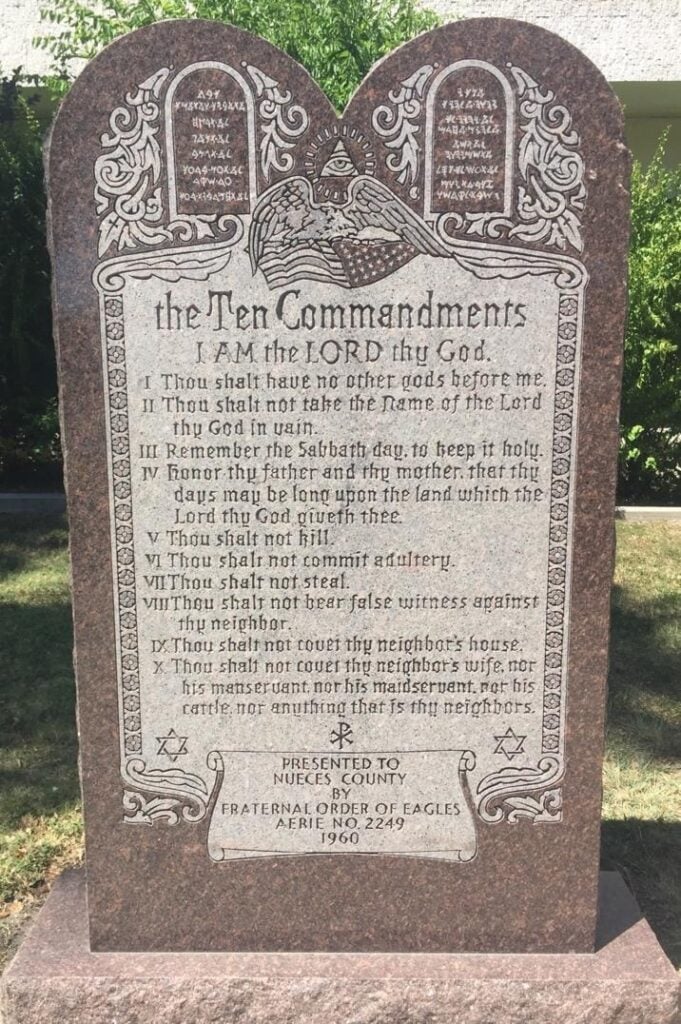

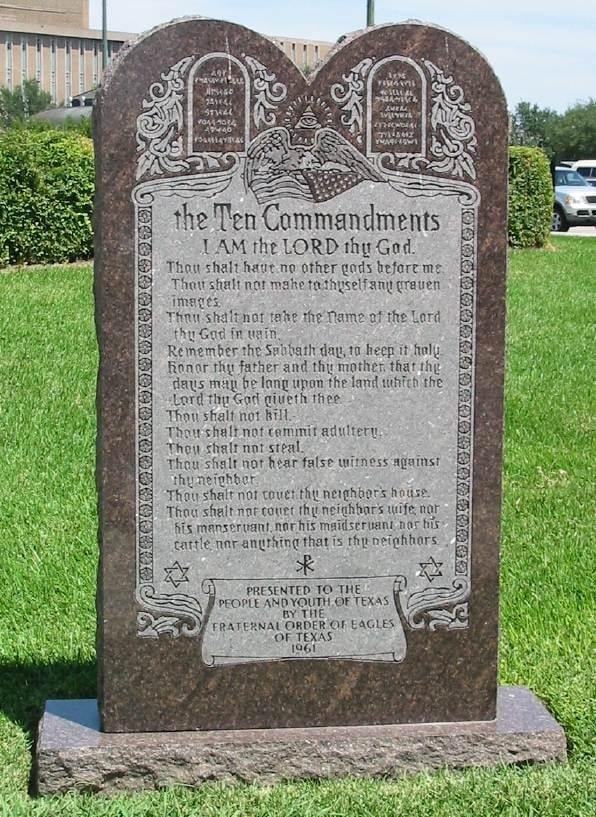

Judge Ruegemer eventually partnered with Cecil B. DeMille and the Fraternal Order of Eagles to help place monuments inscribed with the Ten Commandments throughout the United States. When they were first erected in the mid-1950s, Protestants and Jews immediately pointed out that the numbering system was inconsistent with that used by their traditions.

The Ten Commandments may be found in Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, texts originally written in Hebrew with no chapter or verse numbers (these were added later). English translations of this Hebrew Scripture have been made by Protestants, Catholics, and Jews, but few laypersons can distinguish between them. However, Protestants, Catholics, and Jews number the Commandments differently. For instance, Protestants consider the Second Commandment to be “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,” whereas Catholics consider it to be “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain,” and Jews consider it to be “Thou shalt have no other gods before Me.” (Lutherans are Protestants, but they follow the Catholic numbering system.) Because the first Ten Commandments monuments followed the Catholic numbering system, the text appeared to be sectarian.

In response to complaints, the Eagles altered the way in which the Commandments were presented to overcome “any possible objection to the version of the Ten Commandments.” The most significant change involved removing the numbers before each commandment. Most post-1958 Ten Commandments monuments include this version of the text—including the monument on Texas State Capitol grounds found to be constitutionally permissible in Van Orden v. Perry (2005).

Because the lines of the Ten Commandments on the Texas monument are not numbered, it is possible to read them with thought-breaks in different places. For instance, a Jewish citizen may read the line “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy” as the Fourth Commandment, while a Protestant might read it as the Third Commandment. Similarly, one could understand the phrase “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain” to be either the Second or the Third Commandment.

In 2024, Louisiana passed a statute requiring the Ten Commandments to be posted in public school classrooms. Recognizing that separationist groups would claim that the law violates the Establishment Clause, the statute specified that the “text of the Ten Commandments” that would appear on the posters must be “identical to the text of the Ten Commandments monument that was upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U.S. 677, 688 (2005).” With very minor variations, Texas and Arkansas utilized the same version of the text.

Despite being found constitutional in Van Orden, and despite the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit ruling that this version is “a nonsectarian version of the Ten Commandments,” critics continue to claim that Louisiana and the other states are requiring the posting of a Protestant version of the Commandments. We disagree.

Given that there are no numbers, what sort of argument can be made that the version in question is Protestant? In our view, only unpersuasive ones. In the Louisiana case, for instance, the plaintiffs’ expert contended that the text is taken from the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible because it “uses the words ‘Thou,’ which we don’t use very often these days unless you’re reading from the King James Bible.”

“Thou” is indeed used in the KJV, but it is also used in Catholic and Jewish translations that were available to the committee putting together the Ten Commandments monuments. Presentations of the Ten Commandments are usually drawn from Exodus 20:1–17, but in no display of which we are aware are these verses copied verbatim. This is certainly true with the version in question. Below is the text of Exodus 20:1–3 from the Jewish Publication Society Bible (1917), the Catholic Douay-Rheims Bible (1899), and the King James Version (1611). The language retained in the Ten Commandments text is in bold.

Jewish Publication Society Bible:

And God spoke all these words, saying: I am the Lord thy God, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt have no other gods before Me.

Catholic Douay-Rheims Bible:

And the Lord spoke all these words: I am the Lord thy God, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt not have strange gods before me.

King James Version:

And God spake all these words, saying, I am the Lord thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

The text from the Texas monument and posters:

I AM the Lord thy God.

Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

There are minor differences between the Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant translations, but we submit that there is no good argument that the Ten Commandments text is taken from the KJV. Certainly the use of “Thou” does not indicate that it is Protestant.

This same expert also argued that the version in question is Protestant because it contains the prohibition on making “graven images” but that “most Catholic translations omit” this prohibition (emphasis added). However, the Catholic Douay-Rheims rendition of Exodus 20:4 reads: “Thou shalt not make to thyself a graven thing, nor the likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, nor of those things that are in the waters under the earth” (emphasis added).

This rendition is not an outlier. Every English translation of the Bible approved by the Catholic Church that we consulted includes some version of the command. For instance, the Jerusalem Bible (1966): “You shall not make yourself a carved image”; the New Catholic Bible (2019): “You shall not make idols or any image of things that are in the heavens above”; The New American Bible, Revised Edition (2011): “You shall not make for yourself an idol or a likeness of anything.” It is true that these translations do not include the specific words “graven images,” but the equivalent idea is communicated.

Moreover, the 1921 edition of A Catechism of Christian Doctrine—the classic American Catholic catechism, published in 1885 and which remained the default catechism for American Catholics until the 1994 English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church—includes Exodus 20:4’s command that “thou shall not make to thyself a graven image.” The 1994 English translation of the Catechism contains virtually identical language: “You shall not make for yourself a graven image.”

A final argument made by the same expert is that the command that reads “Thou shalt not kill” is Protestant whereas the Jewish version reads “You shall not murder.” It is the case that recent Jewish translations of this command use “murder” rather than “kill,” but there are Jewish texts that use the latter. For instance, the Catechism for Younger Children: Designed as a Familiar Exposition of the Jewish Religion, a catechism for Jewish children written by Isaac Leeser and first published in Philadelphia in 1839, asks, “What is the Sixth Commandment?” The answer is: “Thou shall not kill.” The answer is identical in the third edition of this work, which was published in 1856.

The distinction between killing and murdering is hardly one made only by Jewish scholars and translators. The English Standard Version of the Bible, translated by Protestant scholars and published by Crossway in 2001, renders this commandment as “You shall not murder.” Indeed, most (but not all) Christians understand the commandment to prohibit the taking, in the words of the 1921 Catholic Catechism, of “the life of an innocent person,” but not a life taken “in self-defense,” in “a just war,” or through a “lawful execution of a criminal.”

In 2005, the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit found the version of the Ten Commandments that would be placed in Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas classrooms to be “a nonsectarian version of the Ten Commandments.” We believe that this court was correct. It is possible to present the Ten Commandments in ways that are clearly Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish, but there is no good argument that the text in question favors one of these traditions over the others.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, sitting en banc, is currently reviewing the Louisiana and Texas laws, and its decision will likely provide crucial guidance for the U.S. Supreme Court’s eventual consideration of this issue. As the judiciary weighs the constitutionality of these displays, it should recognize what the historical record and textual analysis make clear: The version of the Ten Commandments at issue is genuinely nonsectarian. Created through interfaith collaboration specifically to avoid denominational preference and upheld as constitutional in Van Orden, this text represents a successful effort to present a foundational moral and legal code in a manner respectful to Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish traditions alike. Courts should reject claims that this carefully crafted, religiously neutral version somehow establishes a particular denomination’s interpretation of Scripture.

What Virgil Teaches America (ft. Spencer Klavan)

In this episode, Spencer A. Klavan joins R. R. Reno on The Editor’s Desk to talk about…

A Critique of the New Right Misses Its Target

American conservatism has produced a bewildering number of factions over the years, and especially over the last…

Europe’s Fate Is America’s Business

"In a second Trump term,” said former national security advisor John Bolton to the Washington Post almost…