After more than a decade as a demographic laggard, eastern Europe is having a slight “baby boom.” The typical total fertility rate in eastern European countries has risen considerably from the late-1990s lows, narrowing the gap between these countries and their western peers. While some claim these numbers are the result of “retraditionalization”—the push for more traditional values in eastern European countries—the story is more complicated than that.

European governments in Poland, Russia, and Hungary are eager to tout their successes—and there are indisputable success stories. I have written elsewhere about the remarkable fertility turnaround in the deeply religious republic of Georgia, and there is reason to think Hungary’s birth turnaround may have staying power. But demographers have made two arguments that poo-poo these trends: First, that fertility gains are simply a “tempo effect” as women catch up on postponed births from the crisis period in the 1990s. Second, that in the long run, higher fertility will require a shift to more egalitarian gender norms like those of higher-fertility Iceland or Sweden, a shift that is progressing slowly in eastern Europe. Indeed, the rise of right-leaning populist movements seems to have thrown the left-leaning vision of social progress into reverse.

A new academic paper from the Population Association of America challenges these claims. Focusing on detailed data from Belarus, it shows that Belarusian women are having more babies, at younger ages, than a generation ago. At the same time, young Belarusians express more traditional attitudes about which spouse should work and which should stay home with a child. The paper's strongest bit shows that Belarusian women are having more babies, and especially that the share of women having bigger families of three or four or more kids is rapidly rising. It is weaker in showing the return of traditional values, but on the point that prior research has shown to be most significant for a variety of social outcomes (people's beliefs about whether moms should stay home with their kids), the paper did show that younger Belarusians are more conservative. This surprising shift toward more conservative values has been labeled “retraditionalization.”

But there’s a problem with this story. The “baby boom” in Russia and Belarus is collapsing. Even in the poster-child countries of populist pro-natalism, like Poland and Hungary, fertility trends have been unimpressive. The only country in the region to have experienced a really striking fertility turnaround is Georgia.

But if the only successful turnaround is in Georgia, where the baby boom was explicitly caused by a religiously-motivated pro-natalist campaign, doesn’t that mean that retraditionalization works? Can’t we promote conservative values and get a baby boom? Georgia did it!

Not so fast: How you advance traditional values matters. Every major politician in Georgia supported the church-led push for more babies. The man who made the big religious push has a 94 percent approval rating in Georgia. While Georgia’s political environment has been contentious in recent years, debates over external security, terrorism, corruption, NATO membership, Russia, and the possibility of a restored monarchy are all more important than rancorous debates about populism vs. elitism, or feuds over what it means to be Georgian. Georgians basically agree on what it means to be Georgian, and they basically agree there need to be more baby Georgians.

The same cannot be said of some of the most prominent populist pro-natal pushes in recent years. In Hungary, the advancement of right-wing populism has been enormously controversial. Anger at Viktor Orbán's changes has been one factor motivating Hungary’s massive spike in out-migration: Hungary is losing upward of 75,000 people to net migration every year, a far higher rate of outflow than it experienced in the chaos after the fall of the Soviet Union. While the refugees from Orbánismo do not rival those fleeing Venezuelan socialism in absolute numbers, they’re comparable as a share of national population. If advancing traditional family values alienates half the population, any fertility gains will be fleeting at best.

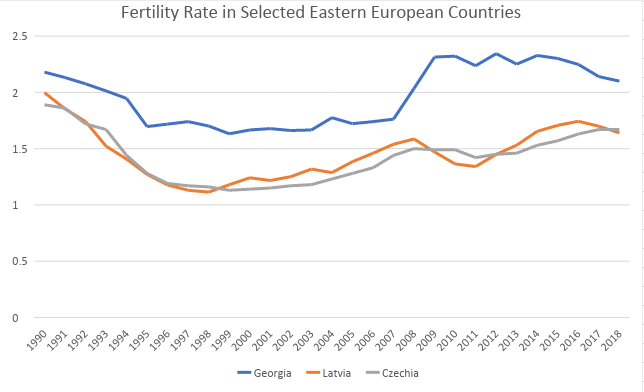

In contrast, the countries that have seen more successful increases in fertility—like Latvia, Czechia, and of course Georgia—have seen more consensus-driven approaches. Throughout multiple elections, governmental reorganizations, partisan realignments, and catastrophe-level impacts of the Great Recession, Latvia consistently increased the generosity of its family supports. Meanwhile, its major political parties are increasingly united with one another—even across ideological lines—due to the external threat of Russian interference and the rise of an ethnic Russian party: Latvian politics are not as defined by ideological polarization.

Meanwhile in Czechia, the governing party is a centrist anti-corruption party carrying on a legacy of successive periods of fairly moderate governance. Election debates have focused as much on institutional problems as on the issues motivating right-wing populism in Poland or Hungary. Czechia’s formal government plan for increasing fertility explicitly aims “to increase confidence in the future and to strengthen the cohesion of Czech society” as a top-tier objective. The Czechians understand that if you boost fertility by splitting society in half, you don’t get anywhere.

In other words, there’s evidence from Georgia, Belarus, and elsewhere that “retraditionalization” can work—especially in countries with consistent government support for families and political climates that broadly support families. But the “fertility stars” of eastern Europe aren’t Hungary and Poland, but Latvia, Georgia, and Czechia. These countries have boosted fertility with relatively little fanfare or controversy under successive governments.

Whether “retraditionalizing” or not, the key point is that support for families and childbearing had broad social acceptance in these countries, and was not seen as highly ideological. This carries a vital lesson for other countries: Pro-natal policymaking needs broad social appeal, enough to convince partisans on both sides that it’s worth getting behind, in terms of votes and cultural heft. Without such an effort, it will be money spent with little impact.

Lyman Stone is an economist who researches demography and migration, and an advisor at Demographic Intelligence.

Become a fan of First Things on Facebook, subscribe to First Things via RSS, and follow First Things on Twitter.

You have a decision to make: double or nothing.

For this week only, a generous supporter has offered to fully match all new and increased donations to First Things up to $60,000.

In other words, your gift of $50 unlocks $100 for First Things, your gift of $100 unlocks $200, and so on, up to a total of $120,000. But if you don’t give, nothing.

So what will it be, dear reader: double, or nothing?

Make your year-end gift go twice as far for First Things by giving now.