What has fueled China’s remarkable economic growth that has lifted more than 500 million people out of abject poverty and positioned it to become the world’s largest economy?

In part, it’s been fueled by the pipeline of market mechanisms, modern technology and Western management practices that former paramount leader Deng Xioaping untapped in the 1980s.

But according to Yukong Zhao, a China expert at Siemens Corporation, these explanations are insufficient given the potential drags on the economy from government inefficiency and corruption, which President Xi Jinping is struggling to contain.

Zhao argues that Western learning and pro-growth government policies have set loose the real creators of China’s economic success—its people and the largely Confucian culture that makes them, in his words, “ambitious, hardworking, thrifty, caring for their families and relentlessly pursuing good education and success.”

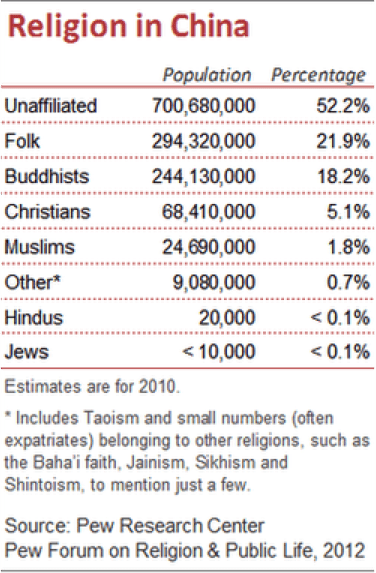

Zhao may be onto something. China is a lot more religious than you might think. Yes, China certainly has more religiously unaffiliated people than any other country, and it is led by a party officially committed to atheism. But what is less well know is that China is home to the world’s second largest religious population after India, according to the latest demographic estimates by Pew Research. This represents a religious bull market when compared to the years of the Cultural Revolution when religion was completely outlawed, believers brutalized, and all religious institutions boarded up.

Today, China has the world’s largest Buddhist population, largest folk religionist population, largest Taoist population, seventh largest Christian population, and seventeenth largest Muslim population—ranking between Yemen and Saudi Arabia in size. This also makes China one of the world’s most religiously diverse nations, something research shows to be associated with economic growth.

But the projected growth of Christianity is of particular note. A study by Purdue University’s Fenggang Yang (cited recently in the Economist) finds that China’s Christian population may become the world’s largest by 2030.

The ongoing growth of Christianity and the growth of China’s economy may be related, according to a new study in the China Economic Review by Qunyong Wang (Institute of Statistics and Econometrics, Nankai University, Tianjin) and Xinyu Lin (Renmin University of China, Beijing).

Wang and Lin find that Christianity boosts China’s economic growth. Specifically, they find that robust growth occurs in areas of China where Christian congregations and institutions are prevalent.

Using provincial data from 2001 to 2011, Wang and Lin investigated the effect of religious beliefs on economic growth. Among the different religions analyzed, they found that Christianity has the most significant effect on economic growth.

Why might that be? Wang and Lin note that Christian congregations and institutions account for 16.8 percent of all religious institutions, more than three times larger than the share of Christians in the general population (about 5 percent).

Such institutions elsewhere tend to stimulate economic growth for individuals and communities, according to studies led Prof. Ram Cnann of the University of Pennsylvania. There’s no reason to believe that they don’t have the same effect in China.

The economic benefits of religious institutions include direct spending for goods, services and salaries, as well as a broader “halo effect.” This includes the real but often unmeasured benefits of religious congregations, such as the safety net and networks provided to individuals, the magnet effect of attracting everything from lectures to weddings, and valuable public spaces that provide communities with centers of cultural, ethical, spiritual and even recreational value.

Wang and Lin argue that Chinese Christianity’s social doctrines may also have economic impact. They suggest that Christian ethics emphasize the overall development of human beings, not just economic development. For instance, they observe that the Christian obligation to be accountable to God and their fellow believers tends to result in legal and rational investment behavior rather than illicit or wild speculation.

It may be that the impact of Christianity identified by Wang and Lin might even reinforce the economic impact of Confucianism identified by Zhao. In a public dialogue at Peking University in November 2010, world-renowned Confucian scholar, Tu Weimin of Harvard, and Christian theologian, Jürgen Moltmann of the University of Tübingen, found commonalities between Confucianism and Christianity. For instance, Confucius’s famous silver rule, “Do not do to others what you don’t want to be done to you,” is a pragmatic mirror image of Jesus’s more demanding golden rule, “Do to others whatever you would have them do to you.”

Wang and Lin also note positive, though inconsistent economic effects from China’s other major faiths, including Buddhism, Islam and Taoism. (Confucianism wasn’t included in their study, and is not counted as an official religion by the government.)

Wang and Lin conclude that the implication is not for the country to favor one faith above another, but to “build a better-informed economics, and in the long run, better policy.”

One clear implication is that the government policy of highly restricting religion, including allowing local government officials to destroy and deface churches in Wenzhou—often called China’s Jerusalem—must be reconsidered. Such restrictive policies may undermine an important source of China’s economic success. Just as China has radically deregulated its economy with successful outcomes, further deregulation of religion would be one way to keep China’s economic miracle alive for decades to come.

Brian J. Grim is founder and president of the Religious Freedom & Business Foundation, as well as an affiliated scholar at Georgetown and Boston Universities, and a member of the World Economic Forum’s global agenda council on the role of faith.

Become a fan of First Things on Facebook, subscribe to First Things via RSS, and follow First Things on Twitter.

You have a decision to make: double or nothing.

For this week only, a generous supporter has offered to fully match all new and increased donations to First Things up to $60,000.

In other words, your gift of $50 unlocks $100 for First Things, your gift of $100 unlocks $200, and so on, up to a total of $120,000. But if you don’t give, nothing.

So what will it be, dear reader: double, or nothing?

Make your year-end gift go twice as far for First Things by giving now.