Ang Lee’s 2009 film Taking Woodstock records an important milestone in the culture revolution of the 1960s, the rock festival and “Aquarian Exposition” held in August of 1969. It does so from an angle that downplays the concert proper—to our surprise the camera never makes it way down to the main stage—and instead focuses on those who attended. It does this through the personal story of Elliot Tibbets, author of the book it’s based on. Funny, heart-warming, and with a particularly impressive use of extras, it’s a solid film, and deserved more attention than it received when released (2009). Its basic limitation is that in choosing to focus on the Woodstock moment, it has to mainly limit itself to the sunny side of the Revolution. Its main strength is its portrayal of how the hippies’ fraternal “Let’s Get Together” love could actually work.

We’ve been considering ’60s Love in a number of my Rock Songbook posts, discerning its intertwined fraternal, romantic, and free-hedonistic modes, but especially dwelling upon the first of these. This film is useful for that investigation, although it does remind us that the counterculture was also about Freedom, as the Richie Haven song that we hear over its credits underlines. In fact, ’60s Love should probably be thought of as just one aspect, albeit a major one, of the culture revolution’s overarching feature, its attempt to embody freedom.

So a fuller summary of Taking Woodstock’s basic shortcoming, which I offer with quite necessary echoes of The Republic, book VIII, is that it only shows you how ’60s Freedom has left the conformist “Oligarchic-Souled” way of the old U.S.A., the one reticent, fearful, necessity-bound, clutching, and drab, for a groovy new “Uber-Democratic” one, unashamed, loving, expansive, giving, and colorful. The film can only hint at freedom’s next logical step into absolute freedom, wherein it becomes audacious, seducing, god-like, commanding, and luxuriously adorned, but ultimately, Painted Black. For there is this further degree of freedom sought by the human soul, which Plato calls “Tyrannic.” Or as we might more quickly say using ’60s mythology: Woodstock begat Altamont.

That is why our best film about the ’60s Revolution remains Oliver Stone’s The Doors. The Revolution was at heart about the Rush of freedom, with inevitable tyrannic and decadent consequences. We have to make some account for the mad, even spiritual, desire to break on through, evinced by so many in the 60s. Still, Taking Woodstock does serve as a useful counter-point to that darker, and I say more comprehensive, view of the ’60s. And despite its sincere affection for the hippies, it has enough of a sense of humor about them to keep things from getting nauseatingly sentimental.

The film makes a strong case that hippie love saved the day at Woodstock. Due to a mishap in publicity, a rumor got out the festival would be free, and in short order a half million rock fans descended upon the rural site. All was improvisation by the organizers and authorities to handle the situation, which everyone knew could degenerate into chaos. And yet, it didn’t. There was one death from OD (heroin), and another from a car accident, but generally the vibes were good, the crowds patient, and the crimes beyond the “victimless” ones apparently few.

The crowd’s practice of fraternal love had an infectiousness to it that the older “straights” who became involved couldn’t deny. We’re shown Max Yasgur, the owner of the farm used for the concert, saying he’s received more kind greetings from “these kids” in one morning than he has his whole lifetime from his neighbors. A working-class guy in charge of servicing the porta-potties also witnesses to their inspiring behavior, and most notably, a state-trooper who says he “came up here expecting to bust some heads,” now admits the overall love-vibe is “getting to him.” We’re see him do his own random act of kindness, giving Elliot a motorcycle ride through the crowd that’s jamming the road—we see him exchanging the peace-sign greeting a few times, and even jokingly telling a hippie with a sign pleading for Dylan to come, to “dream on, buddy.” He’s getting into the spirit of things.

But it’s through the main characters, Elliot (“Ellie”) Tibbets and his parents, and through their relation to their small town of Bethel, that we most vividly see the need that Straight America arguably had for a hippie love invasion.

Ellie spends his summers helping his Jewish parents run their dilapidated and money-losing hotel in the Catskills area. His mother is ferociously stingy, a bit paranoid, and generally domineering, fitting an unpleasant Jewish stereotype to a tee, and his father is beaten-down, in poor health, and fatalistic. What is more, Elliot is also helping to run the local government. Though he is a young man with artistic leanings, a developing openness to gay sexuality, and hip friends in NYC, he’s giving the better part of each year to his parents and Bethel. He’s the good son. The gifted local who stays.

Those of us who read the likes of Wendell Berry and generally try to hold up the virtues of the small-town community might be inclined to approve of Ellie’s “sticking,” but it’s far from clear that it’s good for him. We eventually learn (a few spoilers for the rest of the post) that his mother’s stinginess is pathological, that she’s been squirreling away a small fortune and thus has been using his help and money when she didn’t need to. Moreover, the appreciation the (largely non-Jewish) town-folk of Bethel apparently have for him vanishes when they realize he has secured the big hippie concert a permit.

The Woodstock organizers had a permit with another town revoked, but Ellie already had a permit for a small-time concert he had done in past summers that he could let them use. That action makes him the hidden hero of the festival, the guy who allowed it to happen. But to most of the town-folk it makes him a villain, and they refuse to speak to him, and even pull out anti-Semitic taunts. Their neighborliness has all along been a charade. So his family home and hometown are not only fairly boring and futureless, but also are at bottom very unkind places.

The hippie invasion that comes once the concert is announced is simply too big to even notice the sour protests of the town, but everything it brings to the Tibbets is unambiguously good: Their hotel is filled (it becomes the advance team’s headquarters), their bank-account too. Ellie’s father embraces his now very active landlord and barkeep duties with zest, and their drab lives become exciting with the sudden infusion of interesting people.

It is more than just excitement—the father learns from the freaks, and seems to find a kind of peace in talking with a wise transvestite who serves as their hotel’s security guard (no, we’re never sure if he knows or eventually learns that she’s a he). And the Tibbets’ family pathology become, through some painful confrontations, partially resolved.

The film does not handle the issue raised by Ellie’s eventually apparent homosexuality with the clarity it probably needs to, leaving us uncertain whether the events unleashed by this “invasion” were key to his coming to terms with his gayness or not. He gets caught up in couple of ways in the erotic free-for all, and has a one-night stand with one of the stage construction workers. This might be a key to his personal liberation, but since we get a passing indication that he has already been friends with some gays in the Village who were involved in the Stonewall Riots, we can’t be sure. In any case, the filmmakers’ message (director Ang Lee’s credits include Brokeback Mountain) that Woodstock-ian free love had a liberating effect for gays gets through well enough. However we judge the hippies overall, the film wants us to be grateful for the role they played in facilitating gay liberation. Without endorsing the basic assumptions involved, I’ll just say it’s an understandable point of view.

It is not simply Ellie’s sexuality that is affirmed. His role in allowing Woodstock to happen vindicates his combination of an artistic side with a small-town side. More than that, his father, in a scene toward the end, tells him that he’s been given a new will to live, because of . . . and we fully expect him to say because of all the full-of-life Woodstock people he’s met . . . but instead he says it’s because of Ellie. From his father’s point of view, the love that allowed the Love Fest of Woodstock to happen, was Ellie’s. Everything good about it symbolizes what is good about Ellie. And yes, had Ellie not been up there, doing the tiresome town council business, there would have been no festival. The film means for us to meditate upon the fact that it was not his love for humanity that was key, but his dutiful love for his mom and dad. Again, his mom was using that—but through what the events of the film do for his father most of all, we see its pay-off. He will now leave for good, with greater confidence in himself, with his father rejuvenated, and even with a measure of forgiveness for his mother.

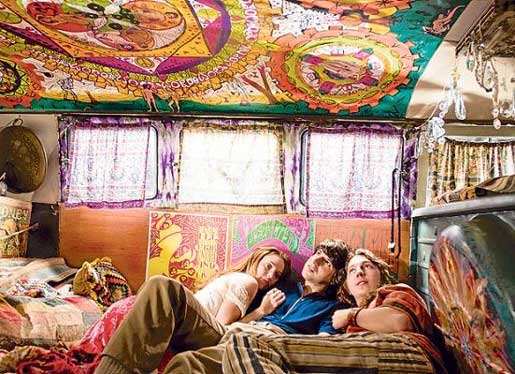

And the concert itself? Well, Ellie does finally get there two-thirds of the way into the film, but gets sidetracked from trying to go down to the stage by a hippie guy and gal on the edge of the crowd, who in an act of spontaneous fraternity offer the tired Ellie a drink. He sits down with them for a spell, and with the Woodstock vibe now making him feel open to anything, takes them up on an offer of acid, which leads the three of them into their psychedelic VW Bus for a trip-session. Of course, it also is a snuggle-session, and a maybe-more-session, for it really is true that the hippie desire to conflate fraternal love with free love points in some way to polymorphous sexuality, to the “Triad,” and to the orgy. What little the scene does show might be taken to suggest that the three of them mainly wind up rubbing up against one another while tripping, but whatever it is they do, it certainly has a sexual aspect.

Ellie still hasn’t made it to the concert itself, and in a nice touch, when he tries again the next day, he is found not merging his being with strangers from anywhere, but connecting with a local high-school friend who’s been pretty messed-up by his service in Vietnam. Together they join the mud-sledding on one of the hills, as there’s no music that day due to the rain soaking everything. It’s pure play, and a healing moment for his friend. The scriptwriter is saying that Woodstock was both the attempt to love and merge with the All, and a down-to-earth good time with your ordinary American friends.

A particular pleasure comes in the exchanges Ellie has with the assistant of the main concert promoter, Ticia—like Ellie, she’s someone at the margins of the big-shot Woodstock players, but who is really more interesting. Ticia and Ellie connect as temporary friends, and until we fully pick up on his gay inclinations we might think she could become a love interest. She has a great bit where she starts to fall into theorizing about the need to not let fear block your ability to love, but then stops herself, apologizes, and says she is so tired of everyone making such guru-like statements. It must just be her sheer exhaustion from days of frantic logistics organizing speaking, she says. She understands that to be real, to really share yourself with others, you have to get past the hippie deep-talk script.

There are other ways the filmmakers retain a certain reserve about hippie-ism: A lot of the concert organizers are shown in a less-than-flattering light. An experimental theater troupe is shown to be utterly obnoxious, and the last scene openly alludes to the disaster of Altamont just around the corner. Moreover, there is a sequence that conveys the come-down, the depressing back-to-reality moment so many of the concerts’ now-bedraggled attendees feel once it is all over.

Still, the lesson is that ’60s love and freedom could at certain moments and for certain people, be the needed medicine. Moreover, whatever reservations we have about the overall career of the counterculture, the filmmakers want to say, it did more good than ill, and undeniably did provide this particular moment of hope.

I’ve already indicated a good deal of what the rebuttal to that viewpoint would be, and so for now, let’s just give the filmmakers the last word—let’s accept their suggestion that it was such a moment, and recognize that their loving recreation of it testifies to a longing felt by many in our day for its recurrence.

It is a longing made painful by the widespread suspicion that another such moment has become impossible.

You have a decision to make: double or nothing.

For this week only, a generous supporter has offered to fully match all new and increased donations to First Things up to $60,000.

In other words, your gift of $50 unlocks $100 for First Things, your gift of $100 unlocks $200, and so on, up to a total of $120,000. But if you don’t give, nothing.

So what will it be, dear reader: double, or nothing?

Make your year-end gift go twice as far for First Things by giving now.