Initially, I wasn’t going to recommend this film. I still cannot really do so for the most persons, and that is not in my book a sign that it is great cinematic art. I am happy, for example, to recommend MUD, the film most scandalously left off this year''s list of Oscar-nominees for Best Picture, to any movie-lover.

My initial ambivalence surprised me, because as regular Carl’s Rock Songbook readers know, I have a thing for re-living and re-thinking the 60s music scenes, and have given special attention to Joan, Bob, and the folkie phenomenon. And ever since some comments here got me digging deep into TRUE GRIT, I’ve learned to respect the cult of the Coen Brothers, and to approach their films with high expectations. I’ve been further encouraged in this by some of the philosophy-prof essays here, and especially by observations from a friend of mine I’ll call my “Coen Brothers guy.” So, I figured I must be just about the perfect potential audience member for this film.

And yet, it left me puzzled and put off. For one, it doesn’t have much of a plot. It was also egregiously depressing--not in the usual tragic, existential, or axe-grinding modes, but in some unique Coen-mode of everyday futility.

But I eventually realized that this is a film that keeps working in your head—it contains puzzles, mysteries, and haunting images, and these eventually drew me to see it again.

***********************************************************

What INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS does is jump into an ongoing story of failure, that of a folk singer. The major reasons for the failure are elusive, but some of the minor reasons are just matters of bad luck. The singer is Llewyn Davis, a composite of various folkies, but particularly modeled upon Dave Van Ronk, the subject of the book The Mayor of MacDougal Street. The Coens have said Ronk was “…probably the biggest person on the scene in 1961 in the folk revival in Greenwich Village, biggest person on the scene until Bob Dylan showed up. But in our minds he was the folk singer, ‘the generic folk singer…’" As the final scene underlines, he was in the same spot and time Dylan was when he was discovered. The film conveys that musically, Davis (i.e., Van Ronk) had extremely high-quality stuff, in Joan’s and Bob’s league, or just below theirs, with the slight inferiority perhaps due to it lacking certain markers of distinctiveness. Surely there were and are some folk fans who regard it as in fact superior.

But contrary to some of its marketing, this film is not a celebration of the Greenwich Village scene or the late 50s/early 60s folk movement. It assumes you know something about those already, and if it does give you some solid portrayals of folk-music performance, what it more typically does is show you the most unflattering aspects of whole scene.

American Bohemia is presented as a kind of special hell within the larger uncaring and over-commercialized American society of the early 60s. We meet at least three pretty despicable bohemian persons, Davis’s ex-lover Jean, the club owner, and the famous folk impresario Bud Grossman; and on a road-trip Davis takes to Chicago, we meet two decidedly monstrous ones, an incommunicative hoody young beat-poet, and a demonically arrogant elder jazz musician addicted to heroin. Even the folk-music loving academic couple that lets Davis crash at their place is revealed to have an exploitative side to their sunny niceness. And Davis himself isn’t terribly admirable.

The legendary bohemian practice of living hand-to-mouth, sleeping on couch after couch, which hagiographic accounts of Dylan often underline, is shown to involve degrading and tension-producing relations for all concerned. We get that flat-out denial of the retrospective romanticization of this period again and again: the road trip across America is awful, meeting Bud Grossman at the famous Gate of Horn is awful, being signed with a legendary ma and pa folk record company is awful, and so on.

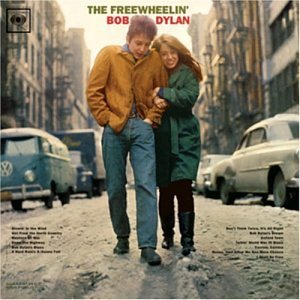

You know the cover of the second Dylan LP, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, where you see young Bob in the rusty suede highways-and-byways-evoking jacket with the bohemian girlfriend on his arm, as they walk down a Village street covered with grimy snow?

Well, imagine that without Bob and his smiling Suzi, so that all we’re left with is the grimy cold street, and maybe somewhere in the corner we see some shivering and beat-up guy with his back half-turned to us. That’s the world of INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS. What it’s telling us, perhaps even too insistently, is that the since-lionized folk/beatnik Bohemia was a cold and dreary place for most of its aspiring artists.

This is perhaps most underlined when, after Davis has undergone his horrific road-trip to Chicago for the sake of playing for Bud Grossman, he finally gets to. The song he plays is beautiful, and Grossman listens intently, but with an unreadable face. We’re so ready for the redemption moment, for Davis’s suffering to pay off. He’s just spilled out the treasures of his soul! And Grossman, without changing expression, says, “I don’t see a lot of money in this.” But words cannot convey how brutal the moment feels.

It’s a deliberately anti-iconic film.

*****************************************************

The lesson from Davis’s failure? Well, I suppose I could quote Tocqueville about equality making each of us fairly-talented ones thinking the democratic world is going to make us stars, or at least reward us with some paying gig, but maybe, there is no lesson. The Coen’s common tack of forcing the audience to confront the possibility of nihilism being true, of human life being essentially meaningless, which for them has usually played out within a crime drama, here occurs in a mundane set of events.

The failure seems fated, as Davis cannot even succeed in getting out of the folk-singer life: when he tries to give up and rejoin the merchant-marine, a nobody’s-fault mishaps (along with corrupt union rules) keep him from being able to. And one scene initially appearing to be a repeat of an earlier one, along with another actually being such, make it seem as if Davis is caught in a time-loop. That''s how cyclical and pointless his life is.

Most of what happens to Davis we can hardly say he is responsible for. Nor does it matter much how he deals with it. He’s no whiner, but his usually toughing things out stoically doesn’t make him a winner. Yes, in two scenes he takes out his anger on persons who don’t deserve it, but there is no suggestion that if had been nice he would have gotten a break. There’s no apparent moral to his story.

In sum, it’s an egregiously depressing story, and pointless beyond reminding us that life often feel pointlessly random, that only the Coens could get away with putting on film.

That’s what put me off. I was focusing too much on the “career” story, or to paraphrase a repeated line in the film, the “what-you-do?” story.

I hadn’t yet digested the significance of the cats and abortions.

Initially, there are two abortions, and two cats, to consider. Subtly but nonetheless insistently, the film suggests that Davis’s responses to them matter, and regardless of how the story of his folk-music career turns out.

Well, actually, there are two abortions that turn out to be only one, and one cat that turns out to be really two.

And actually, careful viewers come to realize that the two cats turn out to be three.

In the most haunting scene in the film, sometime in the middle of the wintry night after he drives by Akron, Ohio, where he knows his two-year old child lives, whom he until recently thought was aborted, Davis encounters one of those cats again, apparently one he abandoned, when it darts out in front of his car. He hits it, stops, and he briefly sees it slightly bloodied and limping off into the night. There is some connection between him having abandoned a child of his to die, by an abortion that never happened, to his having abandoned and now wounded a cat. Both will be wounded for life.

That’s how the cats and the abortions come together, outside the similar confusion about how many of each there really are. But let’s take them in turn.

The most notable instance of energy-wasting mishaps occurring in Davis’s life is when a cat darts out of one the apartments he’s crashing at, and while he runs to grab it, the apartment door locks behind, and he’s thus forced to keep the cat with him in his errands across NYC until those apartment owners return. But the cat escapes while he’s staying at another apartment, because he opened a window to smoke. But, later—saved!--he sees the cat strolling by a café, and snatches it up.

But, as we later learn in a pretty funny scene, that was actually a different cat, a look-alike. So then he’s stuck with this second cat--he doesn’t know who it belongs to. Davis is a compassionate enough guy that he keeps it with him, even as he journeys to Chicago. However, on this road-trip, he finds himself in a situation where he has to hitch-hike in the wintery dawn, or face possible police-entanglements, and it simply won’t work to be thumbing rides, while trying to hold onto a guitar-case and a cat. He leaves it in the car where the creepy addict character is passed out. It poignantly looks into his eyes, and he turns away.

The film in a sense punishes that abandonment, by having him hit apparently the same cat, when he’s driving back the other way from Chicago. What are the chances of that?

Well, they are actually zero, since some earlier dialogue let us know that when he abandoned the cat, the car was less than three driving hours from Chicago. And where does he hit it? Somewhere further past Akron, Ohio, on the way back to NYC. I checked, and the driving distance from Akron to Chicago is 365 miles, likely six hours driving time. Davis has only been in Chicago one day. That means that when he hits what looks like the same cat, he is a minimum 180 miles further East from where he abandoned it about 24 hours before. So, whatever Davis thinks, and whatever the film makes us initially think, it is in fact a third look-alike cat!

But the Coens do their best to keep the puzzle and possibility open, as we later learn that the first cat Davis lost miraculously made its way from Greenwich Village back uptown to Washington Heights, and at one point Davis’s eye fixes on a poster for Disney’s INCREDIBLE JOURNEY, the one where pets find their way home across hundreds of miles of wilderness. So maybe that second cat could have travelled that far on the interstate?

Well, I am ashamed to say that I now have done the internet research to know that among the documented stories of amazing pet return-home journeys, no cat has ever covered 180 miles in a day.

Llewyn Davis has a reputation, to some degree exaggerated by the jealous suspicions of others, for sleeping around. A fact of bohemian life, we might say, of the revolution soon to be mainstreamed. Arguably, a key piece of the male folk-singer mystique.

Two years previously, he arranged and paid for, with what I guess counts as bohemian chivalry, a woman he impregnated to get an abortion (then illegal) from a competent doctor, and in the film we see him do the same for Jean. So it seems we are dealing with a man responsible for two abortions.

But when he goes to arrange the second, in a scene also remarkable for the ridiculous lengths to which the doctor resorts to euphemism to speak of anything but “baby, “birth,” and “abortion,” he learns that the first was never done. His old lover decided to go back to her hometown Akron and have the baby, without telling him. He’s a father.

Could INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS be an anti-abortion film? Well, we can’t tell whether it endorses the moderate pro-choice position of wanting abortion to be “safe, legal, and rare,” but it is almost certainly against abortion itself.

There is only one way it could not be, and that is if you decide that it teaches that nihilism is the truth, revealed here by the pointless failure of Davis’s career, so that his having to obtain abortions for women he impregnated is just another absurd, annoying, and energy-sapping aspect of that, his irrational guilt instincts causing him to have to scrounge for money, and so that his learning that one of these abortions didn’t occur is just another sort of misfortune, saddling him with sentiments that he will have no way to really act upon (it is unlikely the that the mother of the child wants to see him), and probably causing him to draw some kind of superstitious karmic connection between a random coincidence of having hit a cat that looks just like one he abandoned, and his driving by the town his child may be living in. And besides, we know it is only the Coens who have set up the set of coincidences. It is only in movies and old religious tales that such connections are so neat. The truth the film is onto is that even something as apparently momentous as birth and abortion is a function of arbitrary factors. We know the film is onto such truths because it indicates that the very connection Llewyn likely draws between hitting the cat and passing by Akron is based on a factual error.

Well, that’s pretty stretched, and it’s flying in the face of lots of hints from the film.

Item: regardless of the mistake about the cat identity, the film clearly invites us to judge Llewyn poorly for abandoning the second cat, to associate that with his abandoning these two children to death or fatherlessness, and to see the hitting of the cat as a sign of his sin, and of how the one child will be wounded for life by it.

Item: the film clearly portrays Llewyn as considering whether to spontaneously take the off-ramp to Akron, where he has every reason to think his two-year old child is. The accident with the cat is the next scene.

Item: despite the title of the film, which is that of Davis’s solo LP, what is “inside Llewyn Davis” remains pretty unknown to us. However, there is a moment that seems to offer it up, which is when Bud Grossman oddly, perhaps mockingly, says, “play something from Inside Llewyn Davis.” Davis’s choice is an old folk song, “The Death of Queen Jane,” in which a long-in-labor Jane asks for her side to be cut open to save her baby. That is, the heroine asks for her life to be taken for the sake of the baby’s, the very opposite of what is enacted by an abortion. Thinking about such, perhaps even subconsciously, is one of the main things inside Llewyn Davis.

Item: the Saturday night Davis gets beat up by the cowboy-like guy who strangely asks him “what you do?” is the night of Jean’s abortion. This is also the conclusion of the film—so more significant than it ending with Dylan''s first performance in Greenwich Village, is it ending (and beginning) on the evening of the day of the abortion, the one that really happens.

The career of Davis, i.e., the apparent “what he does,” is not what really matters. Earlier in the film, when his sister suggests, that perhaps he should give up on the music thing, he protests the idea by saying, “And what, just exist?”

The anti-abortion message hidden within INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS is that making the way for, and taking the responsibility for, others to exist, may be more important than the apparent path of what is best for one’s “doing,” even for one’s artistic creative doing. Davis should have risked going to Akron to see his child. And he should never have lived in a way that risked bringing children into the world (i.e., conceived), that he was implicitly resolved to either abandon or abort, in the first place.

This seems a bit too pat, however, as if Davis could have applied these lessons and made things right. Or as if a younger Davis could have ever even known these lessons, and thus not have become the Davis we meet. I think what the Coens actually offer, through the strange incidents involving cats, is an opportunity for Davis, and thus us, to glimpse the mystery that lies outside the cyclical trap of a life he was living. They are not saying his pulling off into Akron would have lead to anything solid or otherwise easily got him out of that life. But they really are wanting us to see that missing out on being a father in some unfamous place like Akron is a greater and more poignant loss than missing out on being the likes of Bob Dylan.

Well, we''ll see what my "Coen Brothers guy" makes of all of this. But those of you who have seen it, what do you say?

You have a decision to make: double or nothing.

For this week only, a generous supporter has offered to fully match all new and increased donations to First Things up to $60,000.

In other words, your gift of $50 unlocks $100 for First Things, your gift of $100 unlocks $200, and so on, up to a total of $120,000. But if you don’t give, nothing.

So what will it be, dear reader: double, or nothing?

Make your year-end gift go twice as far for First Things by giving now.