In the last Songbook post, I talked about how “Let’s Get Together” was used by Jefferson Airplane to champion the practice of fraternal love. Such smile on your brother love became a claimed hallmark of the hippie way.

As important was the way the song could connect fraternal love with other kinds. I’ve been arguing that a conflation of several kinds of love, which allowed one to not have to think too hard about what any one of them required, was another key aspect of the hippie way. One of the first signs of this was the way “Let’s Get Together” worked with the poetic “world” set up by the other songs on that first LP, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off. That is, when the song’s central chorus said, Let me see you get together, love one another right now, several other sorts of loving besides the fraternal kind were suggested, given the songs in the immediate vicinity.

What sorts of songs were these? Well, you can listen to the LP here. (I strongly recommend it, especially for those who like the folk-rock sound well enough, but would like a punchier and richer version of it: it’s superior to the other big folk-rock album, the 1965 debut by the Byrds, and perhaps even over the Airplane’s classic second LP Surrealistic Pillow—that’s where Grace Slick joined them, replacing Signe Anderson as the female vocalist.) As originally released, it had eleven songs, and all but three were originals, always with leader Marty Balin having a hand in the writing.

Now Balin’s claim in the album’s liner notes was that All the material we do is about love.

So let’s think more methodically about how that applies, song-by-song:

1. “Blues From An Airplane” A your love is healing me song, from a man who’s been alone some time and really needs some healing. Begins the album on a dark note, but one that opens into hope.

So the love here is eros, or we might say “romantic couple love,” and the love redeems.

2. “Let Me In” A wooing song, on the complaining side, that ultimately ends in rejection. But the key lines are those of the title, which plea for intimacy (and sex), and You don’t even know if there is, one gram of doubt…

So again, love as eros, with the sexual side of it pretty up-front. The love fails, but notice this is due to the beloved’s failure to open up.

3. “Bringing Me Down” A you’re doin’ me wrong so get lost song… As with the previous song, this is the Airplane in a Stonesy mode. The beloved is cheating on the narrator.

Love as eros, and it fails.

4. “It’s No Secret” A celebration of being in love song, here with the idea of declaring it very openly, of betting all upon it: It’s no secret, everybody knows how I feel! As I said in my best folk-rock songs post, “the band seems to be trying to hit upon a kind of white-folkie equivalent to the got-the-Spirit mode of black gospel and soul, and coming pretty near to succeeding.” We might say this is the serious version of The Monkee’s “I’m A Believer.” And we should pose its recommendation of an open, even cheeky declaration of love, against the inauthentic and cowardly modern reserve lamented by a song like The Sounds of Silence”. (But we might also want to think about whether those wise women Jane Austen and Audrey Rouget would entirely approve.)

Love as eros—love as redeeming. The openness about and faith in love is presented as redeeming for the lover, perhaps regardless of what the response of the beloved will be.

5. “Tobacco Road” A cover—a song about growing up as white trash, wanting to get away—at the time associated with a scandalous-for-its-time portrayal of sexuality on film.

Not about love, but longing.

6. “Come up the Years” A you’re too young for me to love, but I do so anyway song. It avoids the creep factor of such songs, by placing the initiative mostly with the girl, by remaining on the fence about whether the narrator will act upon the love or cherish it as what-could-have-been fantasy, and by admitting the impropriety of the love: I…I, shouldn’t stay here and love you, more than I do… A great line, that. Here’s a couple from the verses: …a younger girl keeps hangin’ around, one of the loveliest I’ve ever found, later reprised with a younger girl keeps turnin’ me on, and I’ve been happy to go right along. Blows my mind, steals me heart, somebody help me ‘fore I fall apart.

Love as eros, and with the emphasis on it being forbidden. The way the lover lets himself at least feel this love is presented as redeeming; indeed, despite the declared reservation, everything in the song’s glorious music is coaxing us to root for his breaking of the societal taboo.

7. “Run Around” Mix of the wooing of an old flame song, mixed with complaint about done me wrong (because you run around).

Very emotional shifts, back-and-forth, between declamation and gentleness, and between trepidation and hope. What’s particularly important for our purposes is this dramatically delivered line:

There’s—no—time, to turn away love—I’ve found…

Love as eros, and so redeeming that the assertion is made that it must always be obeyed. But there is also an awareness that in this case it might not work out.

8. “Let’s Get Together” A cover. Discussed in the previous post.

Love as fraternity, primarily, and with everyone.

9. “Don’t Slip Away” Another wooing of an old flame song. The key lines in the verses, are Almost been a year since we’ve been together, and You can’t hide what we shared together, but the key line, the one paired to the intense longing of the title is: Now that you’re here, we should just let it happen! The song is for an instant decision, for total faith in love.

Love as eros. Redeeming.

10. “Chauffeur Blues” A cover, and a pretty rockin’ one. One of those I’m needin’ my sexy lil’ thing on the side blues songs, but here from a female p.o.v. Written by Memphis Minnie back in the 40s. Her longing for her chauffeur, complete with a jealousy-provoked death threat to him, is primarily sexual—in Greek terms the eros is eclipsed by the aphrodisia. What makes it significant as a song from the Airplane, a band presenting themselves as an up-to-date translation of folks and blues spirit, is the adoption of Memphis Minnie’s p.o.v. by a modern educated woman, embodied in Signe Anderson’s very powerful singing of lines like, He’ll be my lover, and I will be his girl! Our modern woman will at times be like that Minnie.

Love as aphrodisia, as slumming lust.

11. “And I Like It” A defense of the new swingin’ life song (i.e., lyrically, like “My Generation”) but directed at a “controlling” lover, i.e., one who wants commitment. It’s like the refusal to be tied down we hear in The Stone Poney’s “Different Drum,” but in blunter mode, in that the narrator threatens to leave if his refusal to commit is not tolerated, and recommends an “open relationship”:

This is my life, I’m satisfied. So watch it babe, don’t try to keep me tied.

This is my life, this is my way, this is my time, this is my dream, you know I like it.

Baby, this is my way, it suits me fine,

so watch it girl, or I’ll leave you behind.

So why not, fit your life in with mine?

The lines which make it more than merely a personal statement, but a recommended stance, are these:

I’ve seen it so many times before,

please believe me babe, when I say it’s a bore,

I need more! I need more! I need more, more, more!

This is my time, I’m doing my best.

This is my way, ain’t gonna be like the rest, no!

So why not, get away from the mess?

The mess, the limiting bore, is obviously monogamous marriage.

So there’s the 60s creed of free love in a nutshell, albeit I guess to Balin’s credit, expressed quite honestly, without the usual happy talk: i.e., it’s no secret that the lover here, and perhaps of the entire album since this is the closing song, is not going to seek marriage. He is going to “Run Around” himself.

*****************************

So, considering the album as a whole, the implicit idea is to retain love as eros, but to use it mainly for the purpose of redeeming blues-ridden modern life, which might well mean to use it serially. In any case, one must not surrender to the society-approved way of institutionalizing love. Forbidden loves must be pursued if felt, and love feelings in general must be followed and obeyed.

True, the album begins with the line Don’t you know, how sad it is to be a man alone?, and thus would seem open to permanent partnership, but we notice that unlike the way the Stone Poneys song at least politely says of marriage it’s not that I knock it, and that unlike the way virtually any other album of love songs up to this point had contained one of those “my love for you will never die” lyrical moments, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off avoids speaking of marriage or of the long term generally. Whether that omission was intentional or not, we may say that the album displays both a willingness to believe in love to the hilt and a refusal to openly hope in it lasting.

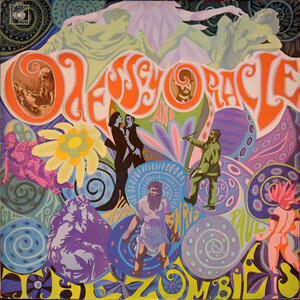

And we might wonder why the skepticism about relying upon eros that the Airplane would soon enough voice with “Somebody to Love” wasn’t given a place within their song-world from the start. On that note we might contrast the love of all love-drama in Jefferson Airplane Takes Off with the more thoughtful and delicate exploration The Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle made of love’s ups and downs, whereby they managed to balance a recognition and celebration of love’s power to redeem (even over the long term) with necessary skepticism and reservation about it.

But to conclude, we certainly feel that to live in the love-world of Jefferson Airplane’s first LP, to imbibe its drama and magic, requires one to remain ever-open to a new love that will replace any old one.

And we feel the album means to suggest that living this way will help one follow the call to fraternal love made by “Let’s Get Together.” Eros, or just lust, for another will loosen you up for, and drive you into, fraternal love for many, and ultimately for all mankind.

It would follow, then, that to really smile on your brother and sister, to really love one another right now, means also to remain open to a new love affair coming about between yourself and one of those you smile upon. And, er, maybe coming about between yourself and several of those others at once, although in that case, it will help if all the parties concerned have read their Marcuse or at least are pretty stoned.

In 1966, with the various all-too-sincere and Science-claiming love pushers hawking their wares, seriously suggesting wife-swapping and group sex and much else as liberating and healthy, as detailed (if you can stomach it) in some of the chapters of David Allyn’s history Make Love Not War (and as delightfully satired in Walker Percy’s Love in the Ruins), there was just no escaping such possible associations in the Airplane’s overall love-advocacy, and in their singing “Let’s Get Together.” And they knew it.

Don’t get me wrong, I am by no means denying that the primary dream of that song is the one pertaining to fraternal love. And I cannot deny the album’s overall beauty, nor even the beauty of the hippie dream, especially in its earliest flowering.

You have a decision to make: double or nothing.

For this week only, a generous supporter has offered to fully match all new and increased donations to First Things up to $60,000.

In other words, your gift of $50 unlocks $100 for First Things, your gift of $100 unlocks $200, and so on, up to a total of $120,000. But if you don’t give, nothing.

So what will it be, dear reader: double, or nothing?

Make your year-end gift go twice as far for First Things by giving now.