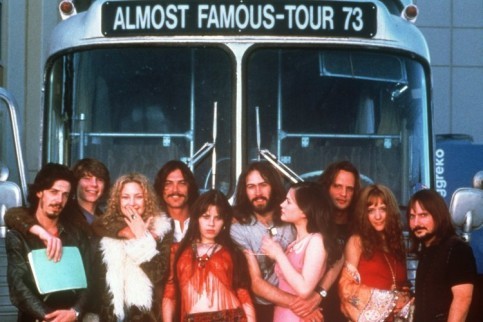

The last Songbook post considered rock Fame and its relations to Celebrity and Honorable Ambition with plenty of help from political philosophy, and a little from ALMOST FAMOUS, too; moving back to the film (which is proving rich enough for, look out, two more parts after this!), this part will be about the lesser sorts of Fame it displays. These are a) that of the lesser rock band, b) that of the groupie, and c) that of the rock writer. All three of these reflect the fact that one can bask or otherwise participate in the fame emanating from the truly famous. This is particularly obvious with the groupies, but even the lesser rock band Stillwater that the film is centered upon is initially seen as an opening band. Every rock band must plug into the already-running engine of rock fame.

Keeping in mind these three distinct relations to lesser fame in the film, what are the key aspects of it?

1) There is, first, the secondary-level rock fame that Stillwater has achieved. It would be one thing if Stillwater’s career had stabilized into a kind routine gigging for a particular audience, but it becomes something else by their seeming possibly on the verge of much bigger stardom. They and their entourage have reason to think that right now, on their little tour and dealing with their little dramas, they could be living out what will later become the stuff of rock legend.

2) Another key aspect of lesser fame is being part of the tour (initially, “on the bus”). This applies even if one is not in the band: the groupies, the manager, William the rock writer, etc., all partake of this. The obvious benefits are the partying, the hotels, the adventure of the road, the buzz of the show, etc.

The essence of this is described as “joining the circus.” Russell tells William that everyone here is trying most of all to avoid having to go home. Again, the situation of the groupie gives us the clearest view. For a groupie to stay with the circus means she needs a space on the tour bus or plane, and a bed in the hotels—she needs to maintain that invitation from the band. Without this, she would be in the situation of having to go home, or, having to live like a desperate female runaway. Like such runaways often do, the groupies do trade sexual favors for their “room and board,” and they know that they are despised and pitied by many for this. The key lyric in the Elton John song “Tiny Dancer” that they and the band so readily respond to, is the one that says the Boulevard is not that bad , that is, not as bad as the tract-distributing Jesus Freaks, in the streets , think that it is. The boulevard life lived by prostitutes and such, like the 70s rock life lived by the groupies and rockers, is not as bad, not as dehumanized, as moralistic outsiders convince themselves it must be. As we saw in my first post on the film , even if Sex is the main thing putting the groupies and rockers together, the groupies remain motivated by Beauty, Fame, and Love, and various mixtures of all four of these factors. Unlike the common prostitute situation, Poverty is not a factor. So they are free enough and aspiring enough that an actual “boulevard” existence would be several rungs or so below theirs, and so if faced with the choice of becoming a real prostitute or returning home, they would, as Russell assumes, do the latter.

Not that they would at all want to, because “joining the rock circus” is a way to get away from conventionality, and perhaps family troubles. The only unkind thing we see the main groupie character Penny Lane do is flip-off a pack of high-school girls on a P.E. run which the bus passes. She decided not to be one of those ordinary girls, and she knows just what the likes of them would say about her. In an interesting touch, she hates the very thing, suburban conventionality, that the song she has named herself after, “Penny Lane,” is nostalgic for.

Compare her with the more ordinary rock fans, who despite William’s mom Elaine thinking they are a “generation of Cinderellas,” do not plunge themselves as Penny does into a life where the boundaries of “real world” become elusive, and in which taking off to live in Morocco is a real possibility, even if some of them perhaps model their style and partying after the idea of such a life. The young women at the Topeka party, who look remarkably suburban and not really given to decadence, who visibly pine when the fame-touched Russell is taken from their presence, well, would Penny Lane flip them off, too? Let us at least say there could be tension if they, Stillwater fans who at most have bought a record or two, and she, the Stillwater groupie, were to mingle. But if she, who seeks to ditch suburban normality but is apparently haunted by it, lives off Rock, Rock itself is shown to live off those who keep, probably because they have to, one foot grounded in that normality, even as the Rock dream of the sumptuous hedonism and famous doings haunts them. My point here is that her escape (and Stillwater’s, and William’s, etc.) from normality is parasitic on its basic acceptance by many others, many of whom she instinctually hates for doing so. The “it’s all happening” scene of the almost famous people feeds upon the more restrained dreaming of the plain “Topeka people.”

Again, Russell applies his “circus” reference, which reminds us that the Rock Tour’s escapist dynamic is in some ways an old one, to “everyone here,” himself included. For any band that has not achieved mega-stardom has to worry about the tour life becoming unsustainable if they do not sell enough tickets; the bands thus also live in fear of “having to go home” to democratic normality. Whereas the 60s Counter-Cultural dream was to bring Liberation and The Happening to everyone, the 70s rockers have accepted that only an elite can fully partake of these.

William eventually learns, to his astonishment and ours, that Penny’s given name was “Lady.” The irony here is not so much in her having become a slut—for honestly, that is what gained her the possibility, in the Rock world, of becoming a kind of aristocrat. Her parents named her to embody aristocratic aspirations, and we get no indication that they were in any sense an aristocratic family; all we know is that they raised her in that rather suburbia-toned town, San Diego, just as William’s mom raised him (and just as my own parents raised me, incidentally). Now Penny becomes, at least on the rock circuit, famous herself. The groupies say to William, “that’s Penny Lane you’re speaking to.” When she arrives at the party at the “Riot House,” she makes a grand entrance, speaking campy French with her “stewardess” riff(inviting comparison of her escape with that of William’s sister)—it is she who is bringing drama to the scene, and her wearing haughty attire like a boa seems absolutely appropriate. And yet this Lady of Rock, who apparently hates suburbia, dubs herself with a name that signals that that is where she’s from. That’s the real irony. She knows she can only be a self-made aristocrat, and hides the fact that her parents hoped she might be one by nature. So Crowe is onto the fact that Topeka, San Diego, and all the locales anywhere there beneath the blue suburban sky have as much to do with Rock as does the Riot House, Swingos, and the “circus.” He’d understand my words on Rock’s Social Geography .

3) The buzz of being up-and-coming, and the fact of the Tour putting you in the key hotels and nightspots also means that you actually do get to hob-nob with other up-and-comers and even the true royalty of rock. At the “Riot House” hotel in LA, it seems every door you pass contains musicians doing their creative thing—you could sit down and jam with them, perhaps; we learn also that while William was doing the unglamorous work of saving Penny Lane from her suicidal OD, Stillwater, by virtue of being at Max’s Kansas City restaurant (and by virtue of being Stillwater) got to hang out with Bob Dylan!

This is part of the reason why the “it’s all happening” line, said twice in the film, and early on by Penny Lane to William, is the heart of the film. The excitement of ALMOST FAMOUS, for William in particular, is that he has not just gotten backstage for one show, into the aristocracy of rock for one night, but has gotten to a place truly inside the scene; this will not simply be key for his rock journalist aspirations, but it also places him at what he takes to be the forefront of the zeitgeist. It is not just “the circus” for him. “Talking with Bob Dylan” is a real possibility. So is putting his own little imprint on the development of rock, the way Lester Bangs did. And, Penny Lane is pretty, and . . . interesting. To be in the rock scene, really in it, is to be in the happening place: musically, intellectually, party-wise, and love-life-wise.

If a conversation between the likes of Russell and Bob Dylan were unfolding over drinks and smokes, with a beautiful fascinating someone like Penny Lane there as well, wouldn’t you want to be there, too? Oh, I know I would. Despite, as the Lester Bangs character describes himself and William, my being not cool even while being as hip as they come. (Okay, sure, I speak mostly of my younger hipness, which won me the “DJ of the Year” award at my college radio station.)

4) One of the main things punk and alternative did was to make this “inside” of rock more readily available. The locus would no longer be the Tour, or otherwise with the Stars, but with Rock Bohemia. The happening place would be “In the City” at the scruffy clubs and hangouts of the scene-sters and less famous bands who deliberately cultivated a D.I.Y. niche-specialized lesser sort of fame. This is where the likes of William would have to go if they wanted the late 70s (and beyond) equivalent of “talking with Bob Dylan.”

In the city, there’s a thousand things, I want to say to you,

about the young ideas . . .

There would still be groupie-like activity, but, some of the young women (and men—such as the Led Zep fanatic ALMOST FAMOUS shows us) who would have earlier become groupies would now form their own groups, as another sort of access to minor fame was now available.

But insofar as Crowe wants to say that the fame-desiring dynamics have never really left the rock scene and continue to characterize it, so that the behaviors of 70s rock stars and groupies can be seen as a more honest expression of what rock is about, however these have since been reshaped by the more bohemian, democratic, and feminist codes adopted from punk on, I think he’s on to something. Rock may have de-emphasized the mega-star, but its obsession with fame, albeit fame of the lesser kind, continues. Indeed, if various dynamics, internet ones particularly, make mega-stardom a thing of the past, then the in-between situation of being almost famous might become the characteristic mode of aristocratic experience available in our ever-more democratic times.

Soon enough, we’ll consider what ALMOST FAMOUS thinks it has resolved by its fairly cheery ending, that is, what it seems its key characters have learned from the story. But before doing so, I will be obliged to return to the lesser fame achievable by the rock writer . For Cameron Crowe, himself such a writer, has set things up so that we really have to ask the following question:

How is the rock-writer like the groupie?

A dicey question for myself, to be sure.