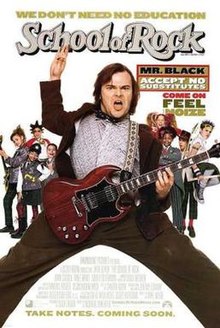

Mr. S. was the alias of the Jack Black-played rocker/teacher character in The School of Rock . That film is one of my favorites from my list of best films about popular music . Very funny, but I also like the way presents an intelligent teaching about rock’s role in our society. Really, it does—read my last post . But it is a teaching quite opposed to the overall stance of my Songbook, and so here I’m going to have to talk back to Mr. S.

I’ll begin by posing a question: which would be better for the kids of our day , Mr. S.’s (i.e., Jack Black’s/Dewey Finn’s) Rock instruction, or lessons from a similarly impassioned teacher of classical music?

It would be the latter.

Let us grant that what Horace Green Prep is doing with classical music is more than a bit forced . Its program has not stirred the students’ hearts the way Dewy Finn’s rock will, nor won their commitment to its musical values. It thus has not done what music education is supposed to do, according traditional theories of liberal education. One easy answer to this is to say that what is needed at Horace Green is a classical version of Dewey Finn, someone truly impassioned about the music. And music class only once a week is inadequate—the school needs to commit, to dedicate a quarter or more of the year to music, the way Finn would . And the way Aristotle would.

The problem with this answer is that these kids will eventually have a world of peers beyond Horace Green, and that they will far more readily impress them by learning rock than classical; similarly, they will find it far easier, in terms of composition and social-happening possibilities, to engage in original creativity via rock. The Zack character can write his own rock song and share it with his peers, whereas there will probably be few opportunities for doing so with classical; moreover, the song he writes expresses his immediate concerns, his frustration with his parents and Horace Green Prep. With rock, he can function as a teenage artist, and right away.

So why do I nonetheless think he’d be better off with an impassioned classical teacher? Because were Zack to stay on the rock track, by his mid-twenties if not sooner, it would become apparent to him how limited a musical form it really is, and that however fun it is to impress 17-year olds, he probably can’t keep doing that in the same basic ways and continue to respect and interest himself . And if he has largely abandoned his classical studies in the interim, but now wants to return to such musicianship, he will know better than anyone how costly the 15-year diversion of his musical passions has been.

That is, the bottom line in judging a music is what it does for us our whole life, or how it functions with other parts of our musical menu in meeting our varied life needs. There is a time and a music for dance, love, war, sadness, story-telling, mourning, worship, etc., and there are modes that suit us better as a tribal people, a rural small-town people, a modern people, or as persons who are uneducated v. those who are. And maybe there is a time for “sticking it to the man,” too. But would we really want to cultivate the music best suited for that, and a few other uses, all our lives? Is that what being modern is to be all about?

When Bill Monroe or Ella Fitzgerald died, we felt comfortable celebrating the fact that they cultivated their respective traditions all their lives. When, say, “Lemmy” of Motörhead passes away(he’ll turn 67 this year), how will we feel about the idea that he kept cultivating his ? Is that what we should want for Zack? If Rock really is an inferior form, in terms of musical sophistication and in terms of serving life purposes, parents have reason try to steer their kids away from it, and perhaps even to “Tiger-mom” their kids into learning musical skills that they might only appreciate the full versatility of later on.

Of course, our imaginary choice between a charismatic rock teacher and a charismatic classical teacher is normally impossible. The more common situation has become no music education whatsoever, a definite cultural decline compared to fifty or a hundred years ago. In any case, the choice the film gives us, Dewey Finn’s passion for rock v. the Horace Green parents’ more surface-than-soulful employment of classical, makes it easy to choose the former.

************************************************************************

The more obvious objection to The School of Rock’s serious teaching is that there is worrying tension between rock’s seediness/snarliness and the innocence of school-kids. While this is finessed by and provides humor for the film, it remains a fundamental problem. The film tries to suggest, particularly in what we see with the drummer kid Freddie, that real commitment to rock tends to discipline the innate unruliness bubbling up in certain personalities. This suggestion is closely linked to the basic (i.e., only dimly Aristotelian) “catharsis” argument you hear from so many persons today. We see that the drummer has authority-issues, but that Finn seems to successfully drive him away from the idea that rock is all about “partying.” By giving him opportunity to unleash his wild side in a channeled way, rock will keep that kid from going really wild.

But where is 11-year old Freddie going to be, vis-à-vis rock’s wilder side, when he’s 21? Wise adults understand the repression-risk any form of forbiddance-employing discipline can have, but contrary to what many peddlers of the catharsis argument suggest, we usually have good reason to be uncertain whether encouraging the expression of rebellious and hedonistic urges through artistry will actually allow those urges to become controlled, or whether it will simply foster them to a greater extent. At the very least, we have to approach this case by case, and at some point, the kid in question has to grow up and choose. And one problem with rock is that it often denies that he must choose: there are not a few rockers who never get beyond the same catharsis, whose music continually expresses a fantasy mayhem and sexual indulgence that they never live out, at least in any obvious way.

Or take the quiet gal who becomes the bass player, Katie. Will it be a morally neutral thing for her if she seeks to become a bass-player in an AC/DC-like hard-rock band as opposed to a cellist? What are most of those AC/DC songs about, anyhow? How will she be expected to present herself on stage? And off stage? What will she feel is the truth about love and sex when she regularly provides a soundtrack for a reductive understanding of it? But maybe she’ll avoid all that and join an artier, less rockier and less sex-evocative band like Veronica Falls . Of course, if reticent artiness is one’s thing, the case for sticking with the cello becomes all the stronger.

The more fundamental question here is whether Dewey Finn’s music can really, over the long haul, teach the children well . Does it not, even in its less hedonistic moments, too often dwell upon one’s resentments and fantasies of power? Or to speak in a seriously classical voice, that of Aristotle and Plato, are not most of the states of character that hard rock musically imitates base ones? Adolescent ones? Or in its more grandiose moments, tyranny-envying ones?

There is a lot more we could say on this score, but the bottom-line is that The School of Rock is Pollyannish about the ease with which young rockers can take a moderate stance toward rock decadence, particularly as they get into their later teens and young adulthood. The film is not blind to concerns that might be classed, regardless of one’s political affiliation, as “socially conservative” ones—it understands that it is not simply the motive of get-your-kid-ahead ambition that fuels the flight to private schools, but also, or even primarily, the motive of get-them-away-from-the-moral-rot. But it ultimately pooh-poohs those concerns, and sets them up as belonging to uptight and ungenerous characters.

One could say that it has to glide by these concerns, or there would be no film. True. The plot rides on this. But that cannot stand as a defense of the film’s teaching , can it?

***************************************************************

A few of you might be confused at this point by my Songbook’s continual praise of rock n’ roll over rock, and by my saying last time that I’d prefer a School of Rockabilly or of Rocksteady. Since both of those were party-time musics, wouldn’t they likewise be morally problematic, somewhat seedy and hoody, etc.?

To a lesser degree, yes. I’ll be speaking soon enough how the dance, and especially at the night club, seldom if ever has its joy-making untouched by unwholesome pleasures and the criminal element. But if the heart of it all is the good-time dance, a community or even a record industry(on that score, I’m thinking of rockabilly/country legends The Collins Kids ) can involve kids.

That is, in the old days especially, teaching good-time musicianship to children or teenagers was not akin to enrolling them in a kind of cause, a veritable priesthood, the way that rock tends to. In fact, it was more along the lines of child labor or family business—see Selena —and thus seldom something the kids being given serious schooling would seek out. It was bread-and-butter work for the musicians, a little break for the dance-hall audiences, and rooted in the music of small communities. It was not a full-on alternative lifestyle that blossoms out of discontent with modern schooling.

Lest you think I’m painting this too black-and-white, you can check out this 10-minute-doc on The Collins Kids story , where we see how the sexual charge of 14-to-17 year-old Lorrie Collins singing adult love songs caused misgivings, but where we nonetheless are NOT in the rock world. And lest you think that children swingin’ it with their grandpa would be lame, or that I’m some kind of paleo wantin’ to get the wimmen off stage, definitely check out this .

One always worries about the kids . . . and in our day, far too much, really. But is our kids’ future really destined to be Rock’s ritualized rebellion shtick, repeated over and over? And are we all pledged to never voice any musical or moral qualms about that, lest The School of Rock guys label us as uptight?