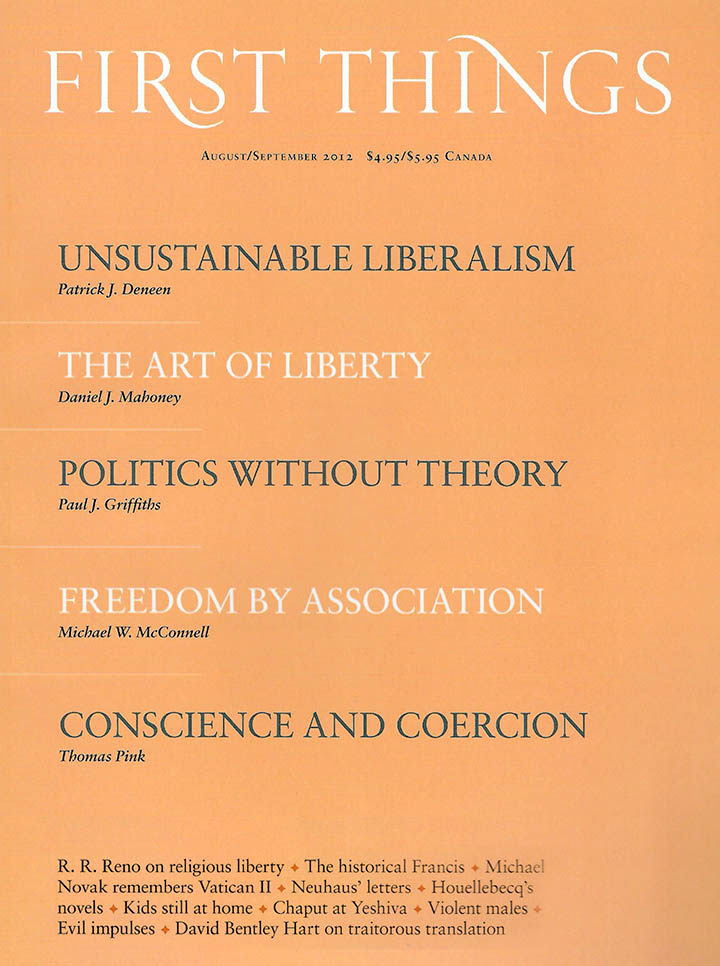

The Map and the Territory

by michel houellebecq, translated by gavin bowd

knopf, 269 pages, $26.95

Man is a peculiar animal, for whom the world is not enough. The French novelist Michel Houellebecq is infamous for his sex scenes, and for being infuriatingly laconic during interviews. One of his novels got him sued for racism; his latest earned him the Prix Goncourt. But his real significance lies in his sense for the peculiarity of the human person, a peculiarity that, in his novels, clashes with modern schemes for living. As a stoic police detective named Jasselin puts it in Houellebecq’s latest novel, The Map and the Territory, “Man was not a part of nature, he had raised himself above nature . . . that’s what he thought in his heart of hearts.”

Jasselin is a minor character, but most of Houellebecq’s inventions share his opinion. Invariably from prosperous Western Europe, usually middle-aged and immature, they live in a time when the great Western experiment of freedom is reaching an apparent endgame: They’ve tried everything (religion, art, money, sex) and don’t know what else to try. They marry late in life, usually bear no children, and often have no friends. Their sense of incompleteness is reflected in their politics.

In Map, we witness “an ideologically strange period,” when “everyone in Western Europe seems persuaded that capitalism is doomed, and doomed even in the short term, without, however, the ultra-left parties managing to attract anyone beyond their usual clientele of spiteful masochists.”

With every book, Houellebecq tries to expose the root cause of this cultural inertia: a failure to adequately address the fact that the world is not enough and that man is uniquely in possession of an outsized longing. “What can we expect from life?” asks another policeman in Lanzarote. “This is a question which seems to me impossible to evade.” He then joins a cult. “The idea of immortality had basically never been abandoned by man,” a depressed comedian declares in The Possibility of an Island, “and even though he may have been forced to renounce his old beliefs, he had still kept . . . a nostalgia for them.”

Houellebecq’s latest novel addresses this same crisis of dissatisfaction. What is different in Map is how the characters deal with this crisis. In previous novels, Houellebecq’s method has been to expand the horizon of possibility for his characters, either through science fiction (a genetically engineered immortal human race in The Elementary Particles) or by imagining a free-love utopia where all are, for a brief moment, happy (the Thai sex resorts in Platform).

If the world is not enough, then make it bigger. But these are always ironic attempts at finding a solution: Suicide is common in Houellebecq’s world.

Suicide happens in Map, too, but in it we also find Houellebecq’s most explicit moral protest against it: “To destroy the subject of morality in his own person is tantamount to obliterating from the world, as far as he can, the existence of morality itself.” Those words are spoken by the novel’s hero, a Parisian artist named Jed Martin, to his father, who will seek assisted suicide in Switzerland. Houellebecq’s least speculative and most “humanistic” effort, Map is mainly concerned with Jed’s life and with the most important encounter in it: with the novelist Michel Houellebecq, sometime during the first decade of the twenty-first century.

What makes Map worth reading, however, is not that Houellebecq plays the postmodern trope of converting the author into a character, or that the book is evidence of a mellower Houellebecq. It’s worth reading because he finds within a realistic story the same crisis of dissatisfaction that in previous novels he represented through fantastic means.

Jed begins his artistic career with photographs of the nuts, bolts, and knobs of the industrial world, which shine like “jewels, gleaming discreetly.” Inchoate in this early work is a contradiction he will explore throughout his life: He is casting an aesthetic gaze—a uniquely human activity—upon the tools that created our technological society. But as soon as his day job as a commercial photographer requires him to take shots of those same objects for a manufacturing company, their aesthetic appeal disappears.

Jed begins to work again only after finding inspiration in another modern artifact: Michelin maps of the French countryside. These move him by the way they capture “the essence of modernity, of scientific and technical apprehension of the world . . . combined with the essence of animal life.” He photographs them and fixes them alongside corresponding aerial shots of the territory they depict. At his gallery opening, a sign near the entrance reads: “the map is more interesting than the territory.”

Visiting his show is a Russian beauty, Olga Sheremoyova, who works for Michelin and becomes the true love of Jed’s life. And so these maps, and the woman he meets through them, help the solitary, eccentric Jed to consider the essence of human life.

This discovery forces Jed to seek a new direction for his work, after the Michelin maps no longer move him. It’s not enough to contemplate the human condition indirectly. He is ready to meet man face-to-face. Ironically, this is when Olga leaves him and he feels heartbreak for the first time.

It’s then that he makes his famous “return to painting” and paints a series of paintings depicting various professions, from horse butchers and tabac managers in his early paintings, to Steve Jobs and Bill Gates in the later ones. But his heartbreak also leads him to a misanthropic conclusion about the “essence” of human life: “It’s his place in the productive process, and not his status as a reproducer, that above all defines Western man.”

The hardware has triumphed. Even as he sees the need to enter more deeply into the essence of humanity and to capture it on canvas, he adopts the reduced understanding of it that his culture has set before his eyes like a veil of ashes. Jed stops painting. He destroys his half-finished rendering of Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst—perfect symbols of cultural dead ends.

Jed finds his way through this impasse only after meeting an actual person: “Houellebecq.” Houellebecq becomes both the subject of his best (and least realistic) portrait and also something new in Jed’s life: a true friend. He teaches Jed as much about affection as he does about the pain of loss: Houellebecq is brutally, absurdly, murdered, and the final third of Map becomes something of a whodunit.

After the murder is solved, however, Jed must still face a final impasse. His final opus is an expression of either resignation or rebellion before nature: He fixes photographs of all the people he has loved in his life (Houellebecq and Olga among them) onto a canvas in front of his home, exposing it to the elements and photographing the results. “Subjected to the alternations of rain and sunlight, the photographs crinkled, rotted in places . . . and were totally destroyed in the space of a few weeks.” Vegetation triumphs over every human project. His aim, Jed tells Le Monde, is “simply to give an account of the world. ”

This is presumably also Houellebecq’s aim, and it’s worth outlining what such an “account” entails. He knows all about the art scene, urban crime, and the EU. But his novels are never merely about “the way we live now”—that obsession of many contemporary American writers, who want the novel to be a critical documentation of society, a challenge to mass media. He has a more philosophical ambition.

Seen from one angle, his novels are illustrations of a materialistic and pessimistic worldview. Yet those illustrations are so vivid that they expose the poverty of that worldview. They reveal the insufficiency of the world, but also the insufficiency of his ideas about it. In this set of contrasts, the mysterious peculiarity of the human person comes into high relief.

Dwelling on this peculiarity, we find the reason for admiring Houellebecq’s fiction: For him, theories never do justice to the strangeness of human life. As he told his Paris Review interviewer, “belief in the soul . . . is strangely persistent in me, even though I never stop saying the opposite.” That’s because it’s the soul that gives him life.

Santiago Ramos is pursuing doctoral studies in philosophy at Boston College.

Image by ActuaLitta via Creative Commons. Image cropped.

Tunnel Vision

Alice Roberts is a familiar face in British media. A skilled archaeologist, she has for years hosted…

The German Bishops’ Conference, Over the Cliff

When it was first published in 1993, Pope St. John Paul II’s encyclical on the reform of…

In Praise of Translation

The circumstances of my life have been such that I have moved, since adolescence, in a borderland…