My pal and co-author of Power Over Pain, Dr. Eric Chevlen, has a very interesting piece in the On The Square feature here at First Things. Eric is a deep thinker and a man of tremendous integrity, intellectual as well as personal. He writes at length here—there is a reason they don’t call him Dr. Soundbite—about health care rationing. I can’t do justice to the piece in a blog entry and I urge you all to read the whole thing. But here is an overview:

My pal and co-author of Power Over Pain, Dr. Eric Chevlen, has a very interesting piece in the On The Square feature here at First Things. Eric is a deep thinker and a man of tremendous integrity, intellectual as well as personal. He writes at length here—there is a reason they don’t call him Dr. Soundbite—about health care rationing. I can’t do justice to the piece in a blog entry and I urge you all to read the whole thing. But here is an overview:

First, he provocatively denies that health care is a “right.” From his column:

It’s a mistake to think of health care as a right. It is not a right; it is a good. Freedom of speech, by contrast, is a right, as is freedom of religious belief. They are privileges that inure to individuals as a consequence of the primordial right, free will. That is why we see them as inalienable. The exercise of these rights does not depend on any action of government, but rather on its inaction. Government may not legitimately interfere with their exercise, but nothing mandates that the government provide us with printing press or chapel.

Health care is different. It is more akin to the other goods which sustain life: food, clothing, and shelter. A well-ordered society exists to protect its members from the unlawful taking of life, and is structured to facilitate its members’ acquisition of these goods.

That makes sense to me. And I think it means that while government has an absolute duty to protect rights, it has far less of an obligation to provide citizens with goods. And when it does, there can be reasonable limits placed on what it provides.

Traditionally, Eric says we have distributed health care based on wealth or ability to pay. I would add that to soften the inequities of such a system, we have long had a very robust tradition of providing charity care—that still exists—for those who could not pay. Indeed, physicians were once expected to provide charity care as part of their professional obligation to society. Many still do.

Eric then explains that health care must be rationed because there is not enough to go around. I disagree with that, by which I do not meant that everyone can have whatever health care they want, but that I disagree it is “rationing” when marketplace exigencies are such that certain levels of care are available for some, but not for others. In those cases, no one is particularly targeted. In contrast, with explicit government rationing plans, people would be put into invidious categories such as age and quality of life, as well as being granted care based on purely political considerations (the diseases with strong political advocacy groups would not be rationed). To me, that’s a whole different kettle of fish, although that may be more a matter of semantics than substance.

In the heart of his piece, Eric describes his work as a consultant for a major insurance company:

I am a consultant for one of the largest private health care insurers in the United States. Because chemotherapy agents are among the most expensive medicines that can be prescribed by a physician, the company wanted an experienced medical oncologist to help manage that expensive resource. When I first accepted the position, I had been worried that I might be pressured to make coverage decisions based on the cost of the medication. I wondered if I would be mensch enough to stand up to such pressure. To my relief, I have never been subjected to that kind of pressure. The pressure I have felt is quite a different one. My supervisors have frequently adjured me of the importance of being consistent in decision making. Since all the members of the health plan are paying premiums for the same insurance, they must all receive equal consideration. The only way to achieve that is by adhering to explicit policies based on sound medical evidence of medical necessity. Medical necessity is our touchstone. It is, frankly, the criterion by which we ration health care. If a service is medically necessary, it is covered. Otherwise, it is not.

The conundrum is surely obvious: What do we mean by medical necessity? What are the criteria of determining medical necessity—and who decides?

This is why I believe in a strong tort system to keep insurance companies honest (a different matter than medical malpractice litigation ), to ensure that those decisions are medically, and not financially, based.

Eric concludes by hooting at the claim by Obamacare supporters that the plan will not ration:

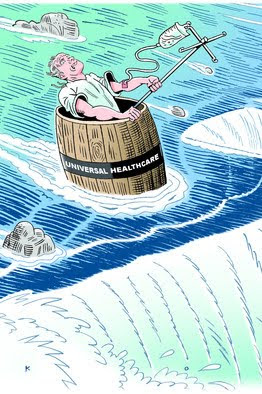

To claim that Congress will devise a new federal health care plan that will not involve rationing is like claiming that it will invent a triangle that doesn’t have three sides. Currently, within the private sector of health care, we have a large number of private insurance companies vying for the business of their customers. They ration health care on the basis of evidence-based medical necessity. The Obama health plan, the details of which are still being worked out, will also ration health care. The alternative to that is an accelerated escalation of aggregate health care costs. But the single-payer system to which Obama’s plan will lead will have no competitor and no pressing financial incentive to please its customers. No competitor for the single payer means no alternative for the patient. We can reasonably expect that a single-payer system of rationing will be largely implicit rather than explicit, and governed as much by cost and political considerations as by medical evidence. Such a system would likely combine the fiscal responsibility of the Postal Service, the customer friendliness of the Bureau of Motor Vehicles, and the smooth efficiency of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

In other words, rationing by government will be far more jackbooted than the cost containment engaged in by insurance companies. You can’t sue the government unless it agrees to be sued. Government administrative appeals seem designed to make you give up in frustration. I think Eric is saying is that we are better off with a robust private sector vying for our business—to which I add, a system leavened by robust patient advocacy and regulatory oversight—-than being straitjacketed into a one size fits all public option that would eventually sap all life out of private health insurance, and result in the kind of disaster we see in the UK.

I believe in a mixed system, but overall, I have to reluctantly agree with Eric’s conclusion that the heart and soul of our health care financing system should be based on private sector distribution, with a safety net to help those who can’t obtain insurance and to take the weight of catastrophic conditions. And when you think about it, I guess that is a lot of what the Obamacare debate is all about.

Time is short, so I’ll be direct: FIRST THINGS needs you. And we need you by December 31 at 11:59 p.m., when the clock will strike zero. Give now at supportfirstthings.com.

First Things does not hesitate to call out what is bad. Today, there is much to call out. Yet our editors, authors, and readers like you share a greater purpose. And we are guided by a deeper, more enduring hope.

Your gift of $50, $100, or even $250 or more will bring this message of hope to many more people in the new year.

Make your gift now at supportfirstthings.com.

First Things needs you. I’m confident you’ll answer the call.