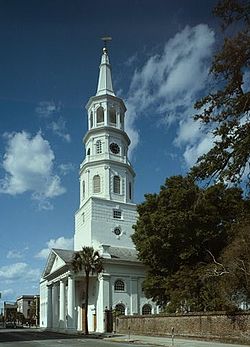

This time it’s in South Carolina. Yesterday’s Wall Street Journal reports (subscription required) on litigation between two rival factions in the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina. One faction, representing the leadership and about two-thirds of the membership, broke away from the national Episcopal Church in November over the national body’s liberal approach to sexuality and other issues. The minority faction has remained loyal to the national body. Both factions assert ownership of the diocese’s property, including St. Michael’s Church in Charleston (left). In total, the diocese’s church buildings, grounds, and cemeteries are worth around $500 million.

This time it’s in South Carolina. Yesterday’s Wall Street Journal reports (subscription required) on litigation between two rival factions in the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina. One faction, representing the leadership and about two-thirds of the membership, broke away from the national Episcopal Church in November over the national body’s liberal approach to sexuality and other issues. The minority faction has remained loyal to the national body. Both factions assert ownership of the diocese’s property, including St. Michael’s Church in Charleston (left). In total, the diocese’s church buildings, grounds, and cemeteries are worth around $500 million.

Church property disputes have become increasingly common in America, as local congregations distance themselves from more liberal national church bodies. In the Episcopal Church alone, there have been a dozen such disputes in the past few decades. Human nature being what it is, each side in such a dispute thinks of itself as the true depository of the faith, with a moral, and legal, right to church property.

Civil courts have adopted a couple of different approaches to resolving such disputes, depending on how the relevant legal instruments are written: the “deference” approach, which defers to the decision of the highest authority within the church structure, and the “neutral principles of law” approach, which attempts to resolve disputes using standard property law principles. Both approaches try to promote church autonomy by insulating internal church government and theological questions from civil court review.

I’m not sure which approach the South Carolina courts take. At the moment, the fight is whether the litigation should be in South Carolina courts at all. The national body is seeking to remove the action to federal court, where, I assume, it thinks it will get a more receptive hearing. Whichever court hears the case, the track record of prior litigation suggests the national body should be confident of ultimate victory –though of course it depends on how the deeds, trust documents, and bylaws are written. For civil-law purposes, the Episcopal Church is a hierarchical church, and courts would normally defer to the highest authority within the church–I assume that’s the national body– on ownership of church property. That’s what happened in a recent case involving the Fall Church in Virginia. If the national body wants to recognize the smaller, loyal faction as the rightful owners of church property, the majority faction will likely have to find somewhere else to pray.

You have a decision to make: double or nothing.

For this week only, a generous supporter has offered to fully match all new and increased donations to First Things up to $60,000.

In other words, your gift of $50 unlocks $100 for First Things, your gift of $100 unlocks $200, and so on, up to a total of $120,000. But if you don’t give, nothing.

So what will it be, dear reader: double, or nothing?

Make your year-end gift go twice as far for First Things by giving now.